Archive State: Imaging Privacy at the MoCP

by Patrick G. Putze

Archive State at the Museum of Contemporary Photography (MoCP) uses collected photographs to offer unique insight into some very specific global situations from the last fifty years. Yet, in doing so, the exhibition points to some very serious investigations into exploitation and one’s right to privacy. Taking the practice of appropriation to a whole new level, six artists present five collections of images, providing wide commentary on social and cultural conditions in a variety of international climates – most of which already have concretely preconceived notions. The offered archives challenge these formulated opinions, such as the inner workings of the East German (GDR) spy machine through recovered images from the former nation’s STASI archive; the lives of young soldiers serving in Iraq; the cultural identities of Middle Eastern youths ahead of the Arab Spring; the state of disorder in crumbling Detroit; and the modernization of China, since the cultural reformation in the late twentieth century. One remarkable side effect from exhibiting these archives is a question of privacy — either intentional or otherwise — from the repurposed archives of others’ discarded images and film.

Delving into the exhibition, we see Berlin-based artist Simon Menner’s archives of the former German Democratic Republic’s State Security Service (STASI), presented by actually having sought and received permission. Since the tumbling of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the archive has been available to the public with certain limitations in place. Some of the more interesting photos Menner offers are Spies Spying on Spies, in which we see several individuals brandishing cameras pointed at someone, or something. One looks straight into the rear view mirror of their car, while another two soldiers in uniform daftly hang out of the side windows of one, and the sunroof of another vehicle, capturing quick images of their target. Here, photography is pictured against itself.

On an adjacent wall is a large 8 x 15 grid of 120 reproduced Polaroids, shot as evidence from secretive house searches that opens up several narratives at once – which individual’s house is this looking into? The images range from interior shots of rooms, to open drawers, to military clothing items and service medals, or something as banal as a Mr. Coffee coffee maker, We learn that the STASI used these Polaroids for the very specific reason that they could put things back exactly where they were. Though, Menner’s choice to display these images constitutes a second invasion of privacy. Drawing attention to the growing national and global problem of state surveillance, one has to ask: should the end result of this archive be more important than the means? Or, phrased differently, can one criticize one government’s venture into the unsuspecting lives of others when accomplishing much the same feat knowingly?

In two separate video installations, compiled entirely of downloaded clips from YouTube, rare glimpses into two often disparate groups are presented: that of U.S. soldiers deployed to Iraq, and also young men from the Middle East on the eve of the Arab Spring. The two artists who created these works are both from the regions they have chosen to represent – a rare case throughout Archive State.

In Dance to the End of Love, Lebanese artist Akram Zaatari outwardly challenges the cultural movements of young adults in Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Egypt, and Oman. The often-playful four channel video installation is composed of seemingly unlikely imagery, chock full of machismo, yet it is not without a sensitive side. Images of young men on motorcycles riding miles-long wheelies are juxtaposed against body builders flexing for the camera; men play the guitar or keyboards, singing together and dancing wantonly around several rooms. The piece is at once humorous and eye opening in the stark honesty of those portrayed – remember, all of the footage was uploaded willingly for sharing with the global masses. The activites of these men, should not really be a surprise to us, though the notion is almost certainly not on par with most commonly held conceptions that pits these assumptions against Western ideologies.

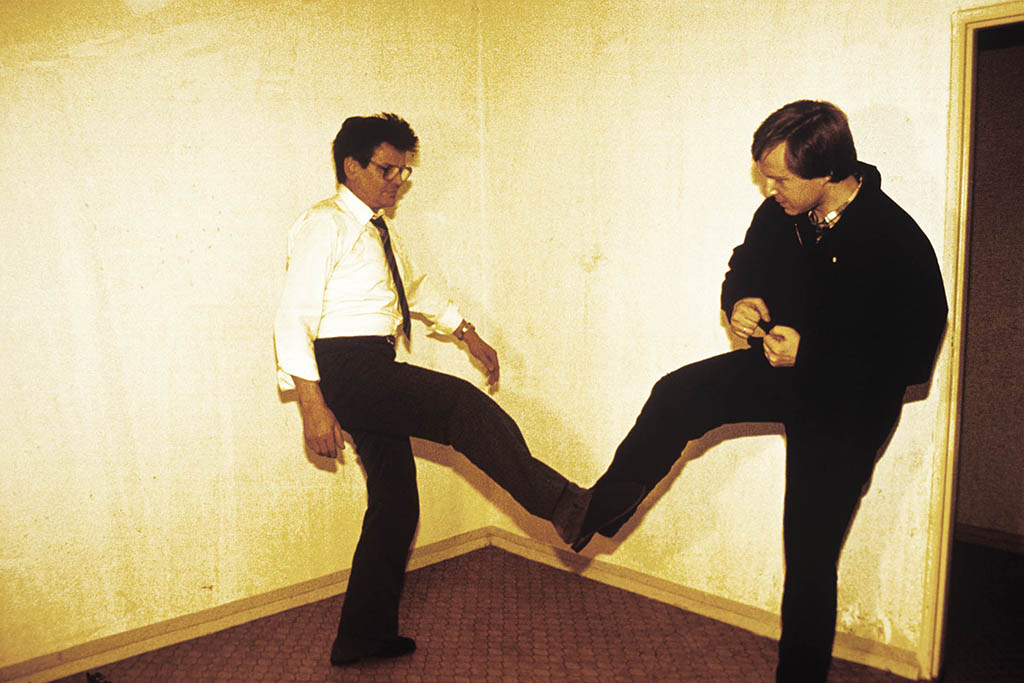

American artist David Oresick presents Soldiers In Their Youth, a twenty-two minute compilation of clips uploaded by U.S. soldiers deployed to Iraq, and their families. In the artist-edited clip, we see soldiers prank each other, fight each other, sing together, write notes to their loved ones, and talk of their experiences. In one segment, several are taking cover on the floor under furniture, as bombs explode in the distance. Oresick produces something both poignant and disturbing. One soldier sings a love song on camera from his bunk, brandishing and cocking his 9mm pistol while finishing the song. The weapon is pointed directly at the viewer. A soldier stopped in his HMMWV asks an Iraqi child is he wanted some candy — instead telling him that he doesn’t have any candy, and offers a hand grenade. The child runs away scared. For these twenty-two minutes, Soldiers in their Youth is at once a look at contemporary war, but also a direct insight not available through traditional media outlets.

Beyond privacy, the impetus of Archive State points more towards definitions of ulterior motives. French artist Thomas Sauvin is a case in point. A collection of over one million discarded 35mm negatives from a recycling plant in Beijing, China, pictures a plethora of “Kodak Moments,” images that belong to the vernacular of experience. Snapshots of birthday parties, family vacations, and local temples are set against individuals posing with newly purchased items, such as TVs, refrigerators, or motorcycles. The citizens pictured in these photographs are starkly juxtaposed against the archetype of American kitsch – a strange glimpse into a nation on the verge of developing into a Super Power over the course of two decades.

When captured, these images from Beijing and the GDR, among others, were never meant for public consumption. Since the dawn of photography, we have revisited quandaries on artist or journalistic exploitation of subjects and subject matter for notoriety, or glorification. Gone are the days when someone like Robert Frank can cruise the country, snapping photos of citizens in their surrounding, in an effort to capture intriguing portraits of a place and time. Whether you choose – or want – to answer the proposition of motive and reproduction in Archive State, the exhibition provides an intriguing aperture to what is most likely to become a lasting debate.

Archive State at the Museum of Contemporary Photography runs through April 6, 2014.