Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo: DIA

by Robin Dluzen

With black-and-white photos of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo side-by-side in studio attire or lip-locked in an intimate embrace, the marketing for Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Detroit at the Detroit Institute of Arts would have one believing that the artists’ romance is at the center of the exhibition. The mainstream appeal of these artists’ individual biographies and their infamous marriage is obviously a major draw for the public; in reality, the exhibition is not bound by the feelings Rivera and Kahlo had for each other. While Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Detroit is an historical exhibition, the emphasis on politics, race and female reproduction feels as urgent and timely now as it did during the years the artists spent in Detroit between 1932–1933.

Diego Rivera was fascinated by Detroit and flourished there; the Detroit Institute of Arts is home to one of the greatest murals of his career, and subsequently the mural studies and preparatory drawings that anchor this exhibition are a revelation. In my experience, exhibitions built around the making of a masterpiece can do a real disservice. Too often, the dissection that occurs through sketches, diagrams and paraphernalia dismantles the aura of the finished piece, though in the case of Rivera and his Detroit Industry murals, these types of minor works both stand on their own and enrich this major work.

Rivera’s Edsel B. Ford (1932), a modestly sized oil on canvas, features the Ford Motor Company’s president (and the mural’s sponsor) in a double-breasted gray suit, posed at a table of drafting tools; centered behind him is an outlined profile of a Lincoln Zephyr. Rivera’s likeness of Ford is exact, its precision paralleled by the composition’s careful symmetry. Though Ford’s face bears a small smile, his expression is cold; his torso and jacket are rendered stiff and blocky. The steely representation of Ford is notably devoid of the motion, emotion and sensuousness that Rivera employs in his representations of workers, peasants, and heroes. While the DIA’s murals read mostly as celebratory of Detroit’s industry (the artist held the machine age in very high regard), works like Edsel B. Ford enhance the critical eye Rivera cast upon the capitalist hierarchies of his subject matter.

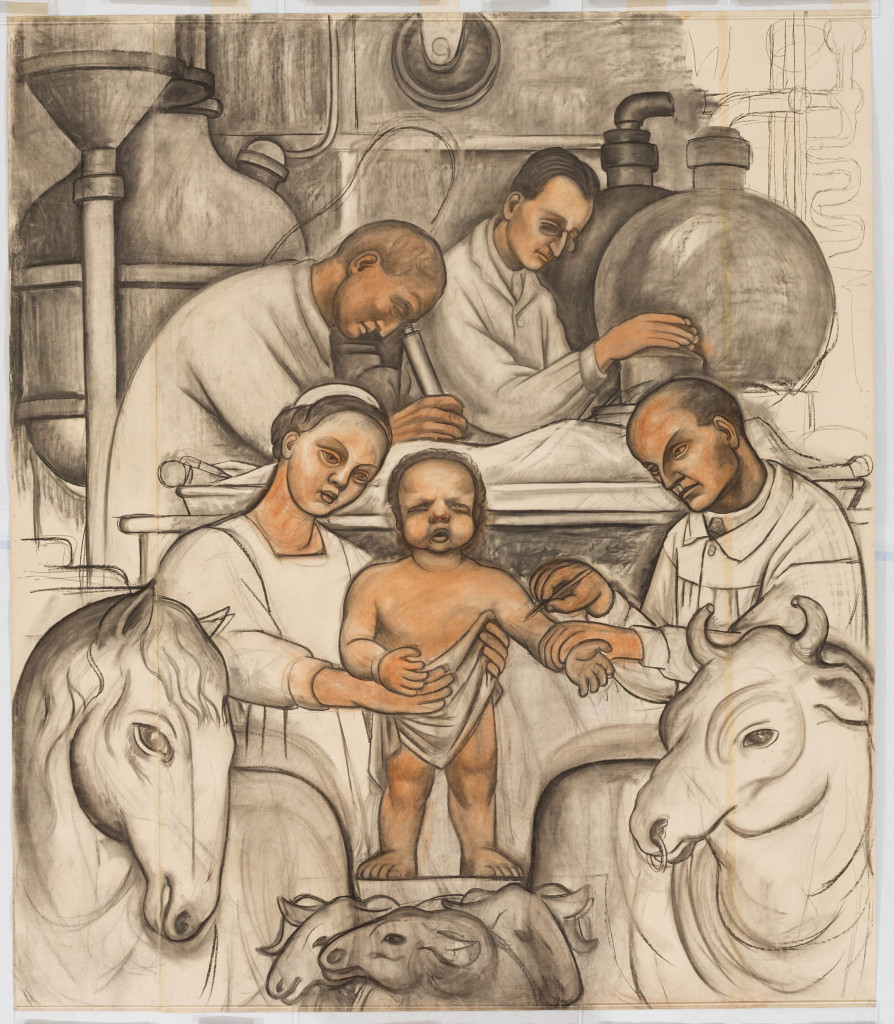

The most powerful works in this exhibition are the enormous charcoal and pigment drawings that accompanied Rivera upon his scaffolding as he painted the Detroit Industry frescoes. To experience the fresco versions of these imageries is to turn gaze skyward, regarding the image high above one’s head as timeless, grandiose, transcendent. The works on paper, as a counterpart, are displayed in typical gallery style, engaging the viewer physically, but to entirely different ends. The full-scale drawing, Figure Representing the Black Race (Second Version) (1932) depicts the imagery contained in one of the uppermost panels of the north wall of Rivera Court. The reclining figure is nude, a handful of minerals in her palm. Though her body is rather unspecific, viewers are informed that her face is that of a local woman employed as a maid at the hotel in which Rivera and Kahlo were living. Confronting this nineteen-foot drawing head-on not only makes the monumental more intimate, but serves as a reminder that over 80 years ago, Rivera was taking a pointed stance to include non-white bodies in the white-male-dominated institution, and that to this day our institutions remain guilty of the very same racial imbalance.

Unlike Rivera, Frida Kahlo was quite miserable in Detroit, and her artistic output of this timeframe is scant. Filling out her half of the bill is a selection of borrowed major works that Kahlo created after leaving the Motor City, some diminutive doodles and exquisite corpse games, and an abundance of signage and text outlining the grim details of the botched abortion and later miscarriage the artist suffered. Though, of the few completed paintings from these Detroit years, My Birth (1932) and Henry Ford Hospital (1932) are true masterworks. In both, beds, fetuses and bleeding female bodies feature prominently, as they would in the paintings following her 1933 departure. While an unflinching discussion of female reproductive issues within an institution is an admirable risk, one can’t help but feel as though the cult of her personality is doing the heavy lifting in Kahlo’s portion of the exhibition.

Indeed, Kahlo’s practice is an autobiographical one, but using Kahlo’s famous biography as the focal point of her practice is nothing new. It’s difficult to keep Kahlo’s cult status from ruling any exhibition of her work, but it can be done in a way that exemplifies her aesthetic and art historical impact (see the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago’s Unbound: Contemporary Art After Frida Kahlo.) In Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Detroit, the exhibition is structured so as to create a direct comparison of the two artists, and the imbalance between them is obvious. For Rivera, the re-contextualized drawings reveal a different and more complex perspective to the understanding of his oeuvre. In Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Detroit, viewers are given a fresh take on Rivera as a maker—especially in the context of a project that conflates such a conflict of his interests: Marxism and Fordism. Unfortunately for Kahlo, her artistry is not allotted an equal opportunity for reexamination, and the story of her trauma trumps the artwork on display.

Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Detroit at the Detroit Institute of Arts runs through July 12, 2015.