Potential Metamorphosis: Helena Almedia at the Art Institute of Chicago

by Ruslana Lichtzier

Helena Almeida, a Lisbon native, has been one of the leading figures of the Portuguese art scene since the late 1960s. She represented her country twice in the Venice Biennale and has exhibited globally, and yet her current exhibition, Work is never finished on view at the Art Institute of Chicago, strangely, is the artist’s first museum show in the United States in over a decade. It is strange that Almeida just received her first solo show, though one should be surprised, since the current statistics still show an insane gender-based gap in the arts: only 27% of the 590 exhibitions by nearly 70 institutions in the U.S between 2007 and 2013 were devoted to women artists.

Rather than presenting a retrospective, the museum’s curator Kate Nesin and her team chose to feature Almeida’s most recent body of work, which presents large-scale black and white photographic prints. Each of the images, except for one, exist as records of the artist’s movements in the studio. The photographs, elementary in nature, are a final step of a long and hidden studio process; the bodily compositions are drafted first by hand, then rehearsed in front of a video camera, before lastly being rendered as unique photographic prints. The compositions register the artist’s body in specific poses, at times aided by a limited set of prompts: two mirrors, one chair, a wire, three sheets of paper, a set of clothes, a loved one.

A close view photograph presents the artist’s hands leaning against her legs, while her feet bow towards their sides. In a simple choreography, ten fingers, ten toes, two arms, and two legs become a singular sculptural composition. The status of the image remains undecided: does it exist as a photograph, or rather as a reference, as a documentation of a performance?

Almeida, who was trained as a painter and still considers herself one, would say that the works exist as paintings. The feminine performativity paired with the accentuated photographic grain points back in time, toward the 1960s and 70s, while the scale brings us back to present. Throughout the exhibition, the formal cross-generational suspension goes unresolved, and I am not sure what to think of it; but if I am letting it rest, a different reading opens itself up, that of that of the exhibition being a product of an artist in her late career.

The aerialist works, belonging to one of several major sequences dating since the 2000, were created when Almeida was 66. Today she is 83 years old. The hands and legs of the figure I am looking at, in a print entitled To Seduce (2001), are those of an elderly person. The image presents a skin that is gloriously creased by a lifelong touch of the sun. The photograph, that is at once both aggressive and elegant, is not only a conceptual exercise, but rather a record of a specific women artist at work. My reading disobeys Almeida’s narrative; in it, she repeatedly insists on not producing self-portraits, but rather a utilization of a body as a tool—yet, I cannot resist myself, simply because it is not often that a late career work by a women artist enters the contemporary exhibition sphere, specifically not let alone work that features the artist’s aging body. Still, it is worth pausing on this moment of a disavow, where the writer refuses to bow to the narrative the artist insists on. I put down the critic’s hat and step aside from being a self-assigned judge of merits and faults of the work. Instead, by writing through my inescapable temporal limits, I strive to reach a sort of temporary understanding of the works’ ever-changing nature. Simply, I ask myself what this work has to tell me today.

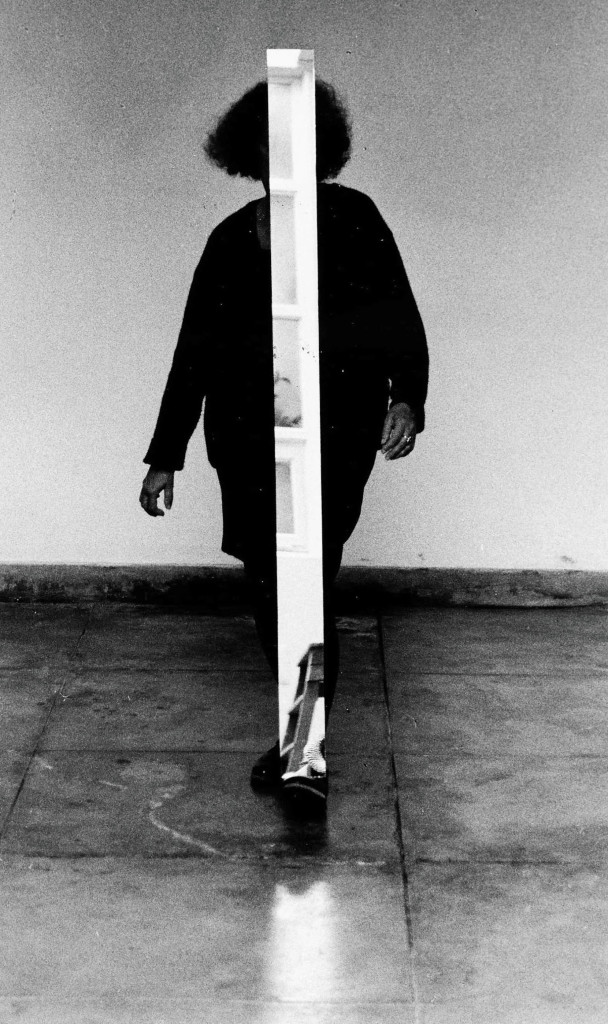

Two photographs, Inside Me (2001), operate in a complementary balancing act, against each other. In one, a narrow mirror leans vertically between the artist’s forehead and her feet, while the artist steps forward. In the other, the mirror leans between the back of her head and the floor, while the artist is stepping away. The diptych presents a double image. The presence of the mirror suggests a reading via psychological tools, and in relation to an assumed interiority. Yet, Almeida’s mirror does not reveal her liking, her subjectivity is being kept away. Instead, it mirrors a fragmented image of the artist’s studio, her space of work. The two photographs are a proposal of a sort; by positioning the mirror in the center of her body, Almeida suggests an opening of a body, her body, to Work. The photographs propose a break from the given isolation of subjects from objects. The artist, meaning subject, desires to enter the world of the objects. She produces work that defies its boundaries and enters the body

To Embrace, a diptych from 2006, presents the artist and her husband, Artur Rosa, who is also her primary photographer, embracing one another, while standing. As in all of Almeida’s work, one cannot read the subjects’ faces—and yet, it is impossible to ignore the tenderness of touch. An arm rests against the partner’s back, the head softly settles on the other’s shoulder. Almeida and her husband, stand firmly, both dressed in black, as if about to merge into one body, one form. Only Rosa’s white hair pulls me away from completing this potential formal metamorphosis. Through the evidence of the couple’s age, my mind steps on a trail that goes through the years of love and an intimate partnership—a partnership that has traversed the boundaries between domestic life and work—and now faces the approaching physical decline and the unavoidable limit of the human body.

In 1998, Almeida stated that “we look at the body and see that it ends abruptly at the feet and the hands. It finishes there. There is nothing more—it is like the edge of a cliff overlooking the sea.” This exhibition, which belatedly introduces this artist to the American public, lyrically highlights not only the physical boundaries of the human body, but also the temporal ones. Finishing this text I wonder about the women that were not granted a museum stage, disappearing from the collective memory. The work is never finished; or rather not in a near future.

Helena Almeida, Work is never finished was on view at the Art Institute of Chicago from June 29 – September 4, 2017.