In a (Black) Way: Three Chicago Artists Push the Limits of Blackness

by Susan Mackey

In the catalog essay for the 2016 exhibition Blackness in Abstraction at Pace Gallery, curator Adrienne Edwards writes, “Blackness fundamentally has to do with the realm of possibility.”1 The three Chicago-based artists profiled here—Nneka Kai, Unyimeabasi Udoh, and Rohan Ayinde—are all using blackness in abstraction as a formal and conceptual tool in their work. “Blackness in abstraction,” according to Edwards, “proliferates as a resistance to figuration and realism in visual representation, and in so doing it elides transparency, immediacy, authority, and authenticity.” Nneka, Unyimeabasi, and Rohan all mobilize the color black toward different ends, but in an effort to challenge viewers’ understandings of their bodies in space.

I. Nneka Kai

I arrived at the artist Nneka Kai’s studio on a Thursday at noon, just as she was preparing work for an afternoon critique. As she welcomed me in, her voice betrayed how tired she was—she had just installed work in the Master of Fine Art (MFA) thesis exhibition less than two weeks prior, and she was busy creating new work for a critique later that afternoon. On top of all that, she would be appearing as a model for a jewelry show that evening.

Entering her studio, I tiptoed carefully around her newest piece, an assemblage of wood painted black, lying on her studio floor. “I have several projects going on at the same time,” she tells me, “but they are all speaking to line, sound, blackness, abstraction.” On the wall behind it hung another work: a portion of a white plastic picket fix, placed just above eye-level, with what appeared to be thick tufts of Black hair suspended from the bottom, forming braids that connect the fence to the ground. Although she is tired of looking at the piece—it has been hanging in her studio for over a year—it is the impetus for her current work, which is an exploration of line (because, after all, what is a braid except for three lines intermingling?).

Nneka uses the color black to deliberately signify Black women, but it is a tenuous relationship between the signifier and signified.

That is what I feel like can be so complicated, but also very interesting, because, I am talking about Black bodies but if I am thinking about Black bodies, Black bodies are not just black. And what does it mean to take on that blackness? I do performances where I paint my whole body black and then I perform with objects, and what does that mean? Black is in terms of variations—black blue, reddish black—how are these colors interpreted in certain lights, mixed with certain things, added to a different material, painted rather than stained.

The work that Nneka showed for the SAIC MFA Show, and more recently at Material Exhibitions, is a sculpture entitled Portal (2019), a mobile constructed of black yarn and steel. The cylindrical structure hangs above eye level. Its shape undulates in size; it is roughly 9 feet tall, only a couple inches wide at its most narrow point and 3 1/2 feet at its widest. Ten black steel hoops are connected to one another by a web of black string, forming a permeable pillar. It’s tricky to discern exactly how the structure is created; are the hoops caught in a tunnel of thread? Or are they the support that makes the structure possible?

During one critique, a fellow student remarked that portals are spaces that one enters to be transported somewhere else, but in Nneka’s work, viewers are prevented from entering. This is a deliberate gesture on Nneka’s part—in much of her practice, she is playing with notions of transparency and opacity, accessibility and inaccessibility, particularly as those concepts relate to Black women.

“You are purposely not allowing us inside that realm of the Black woman,” I confirm.

“Yes,” she tells me. “You can kind of see it, and try to interpret it, but it is all abstracted lines and forms. You are kind of in awe of this structure and how it invades your space. It’s saying to the viewer, no—you can’t go this far.” Nneka takes inspiration from the poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant, whose writing on opacity has been instrumental for those artists working in the tradition of radical Black aesthetics. In his essay “For Opacity,” he writes, “In order to understand and thus accept you, I have to measure your solidity with the ideal scale providing me with grounds to make comparisons and, perhaps, judgments. I have to reduce.”2 Glissant calls on us to “displace all reduction” and replace it with opacity.

Nneka recounts watching a visitor in the exhibition turn a corner and, upon encountering Portal, abruptly stop in their tracks. She owes this to the assertive quality of the color black. “It is really present. And it holds itself, even though it has these minimalist aspects. And then there is the contrast of the white walls. It allows people to interpret the color but also the structure. It is an absence but also a presence.” Black is, in the words of the Afro-pessimist scholar Jared Sexton, a “paradox or problem of beginning and ending, being and nothingness.”3 Nneka clearly enjoys the confounding nature of the color black as well as the materials she chooses to work with.

“It’s very interesting,” she tells me, “I have been interpreting them, and just being with them, and they’re very still. There is so much movement in the piece itself, but hanging it’s just fixed. And I didn’t expect that—for them to be like a pillar. I am thinking about these shapes being like a foundation for a building, or a house, and these portals being pillars and the foundations of a society. And, of course, I am thinking about how America has been built off the backs of Black people.”

While the metaphor of a portal may draw easy associations with Afrofuturism, Nneka is quick to dispel this connection. Part of her aversion has to do with her material; she is fiercely loyal to fiber and craft, largely because of its long historical connection to Black artistic practice, and is unsure of how it fits into an aesthetic practice that seemingly favors new technologies. But beyond material concerns, Nneka is also wary of the escapism that Afrofuturism offers. “I want to be grounded with the Black women who are here right now, but also pull from the past. I feel like the fantasy of Afrofuturism is beautiful, and we can imagine these beautiful futures, but the work that needs to be done now to make those futures is very important.”

II. Unyimeabasi Udoh

Unyimeabasi has a wonderfully dry sense of humor, which, considering the existentialism apparent in their work, may seem surprising or completely appropriate, depending on your own sense of humor. For the SAIC MFA exhibition, they showed an installation entitled My Country (Object Removed for Study) (2019). A stand-alone wall has been painted black, and in front of it stand four pillars, also black, holding nothing. Their vacancy is marked with enamel placards inscribed with the words, “Object Removed for Study.” They are museum plinths whose artifacts have been disappeared.

The plinths function as place-holders for Unyimeabasi’s family members, as indicated by their labels—the missing objects are all titled “Mask,” and their ascribed subjects/makers are “My brother,” “My mother,” “My father,” and “My self.” Each label includes a line that speaks to the individual’s relationship to their Nigerian identity. Unyimeabasi’s mother’s, for example, reads, “My children are Annang. My children will not be.” It’s a line that, Unyimeabasi says, alludes to their family’s tenuous relationship to their Annang heritage— Unyimeabasi’s mother was born in Nigeria, emigrated to the U.K. to attend university, and her children are American-born and do not speak Annang.

“It was a way to work through sort of my own feelings of who am I, where do I belong, in what ways has my family been removed from these various places… Removed from Nigeria but also removed from the UK, removed from this sort of lineage, and how will I fit into that.” The labels deliberately mimic the format of the British Museum, the quintessential colonial museum. Each label includes an acquisition number which, in the traditional museum context, is the year that an art object was acquired by the museum. In My Country, the acquisition number for each mask is the year in which the respective family member was first able to vote in the United States—the year they became part of this national “collection.”

The label for Unyimeabasi’s mask—the one whose maker is “My self”—reads, “My country is a hole, and I take comfort there. I, too, am empty.” This feeling of pessimism infuses the breadth of Unyimeabasi’s practice. “I am really interested in surface, in absence, nothingness, this idea of surface without depth,” they tell me. “Much of my work has to do with absence, a void, the color black. It is the presence of absence. It is a thing, but the thing that is shown is nothing. My work is not so much pointing to the absence as it is the absence. Like a coin that when you flip it over you actually can’t because there’s not another side. It infiltrates my work in other ways. Sometimes it is more straightforward, and other times it is trying to evoke a feeling of emptiness or futility—trying to communicate a feeling of emptiness that is not always negative but expresses itself in different ways.”

My Country is a stark critique of museum collections. For the last year, Unyimeabasi has been paying special attention to the ways in which African art is displayed in museums, which has included a trip to the British Museum and ongoing visits to the Art Institute. The title of Unyimeabasi’s work comes directly from their experience viewing Kerry James Marshall’s Africa Restored (Cheryl as Cleopatra) (2003). The work is an assemblage: the shape of Africa is cut of plywood and thickly coated in black latex, while gold chains and medallions featuring photographic portraits of Black freedom leaders are layered on the surface. Unyimeabasi’s immediate thought upon seeing the work was, “Wow. My country is a hole.”

Unyimeabasi is skilled at seducing their viewer with surface, the slick skin of their work. In another body of work, one that also takes a cue from institutional critique, they appropriate “Old Master” portraits from the Metropolitan Museum to highlight Black subjects. The series is produced as post-card sized prints that have a glossy, highly reflective surface. Each card is double sided and printed with inverse images; on one side, we see the face of Jean-Léon Gérôme’s Black subject in his painting Bashi-Bazouk (1868-60), emanating from a black background, and on the reverse we see the same portrait, but the subject’s face has been blacked out. Flipping the card back and forth in your hand reveals and conceals the Black subject, and at times captures the sunlight that is reflected off the glossy surface.

Unyimeabasi’s work echoes that of the artist Fred Wilson, who has been making work related to institutional critique for at least twenty-five years. Wilson is interested in “Question[ing] not only the artist’s relationship to the museum but also how museums present information and how the cultural production of various peoples gets presented in very different ways.”4 My Country works similarly. Wilson asks his viewers to consider, “Besides, the visual of the object, what is the visual of the space doing to the object, doing to your experience?”5 In the dense sea that is the MFA show, Unyimeabasi’s installation is an island, or rather, the inverse of an island: a hole.

III. Rohan Ayinde

The morning after opening night of the MFA Show, in which Unyimeabasi and Nneka show their work, I make my way into the Loop to attend SAIC’s Graduate Visual and Critical Studies (VCS) Thesis Symposium—or, as presenters this year called it, an “Unsymposium”—held in the school’s ballroom. I am there to see a performance by Rohan Ayinde, a poet and artist in the VCS department and one of my co-curators for the MFA exhibition.

Rohan has, for the last year, become increasingly interested in the conceptual possibilities of black holes, and his performance feels like a pastiche of all the ideas he has been exploring. From my position standing in the balcony I watch Rohan, donned in a black thermal onesie, face his audience from the ballroom floor, which is coincidentally checkered with black squares. Behind Rohan stands a minimalist sculpture—a black square suggests a floor, or interior, from which steel bars jut upward and connect to one another. It is like the frame of a house, toeing the line between interior and exterior. Scattered around the sculpture are four black music stands, holding pages of texts from which Rohan reads.

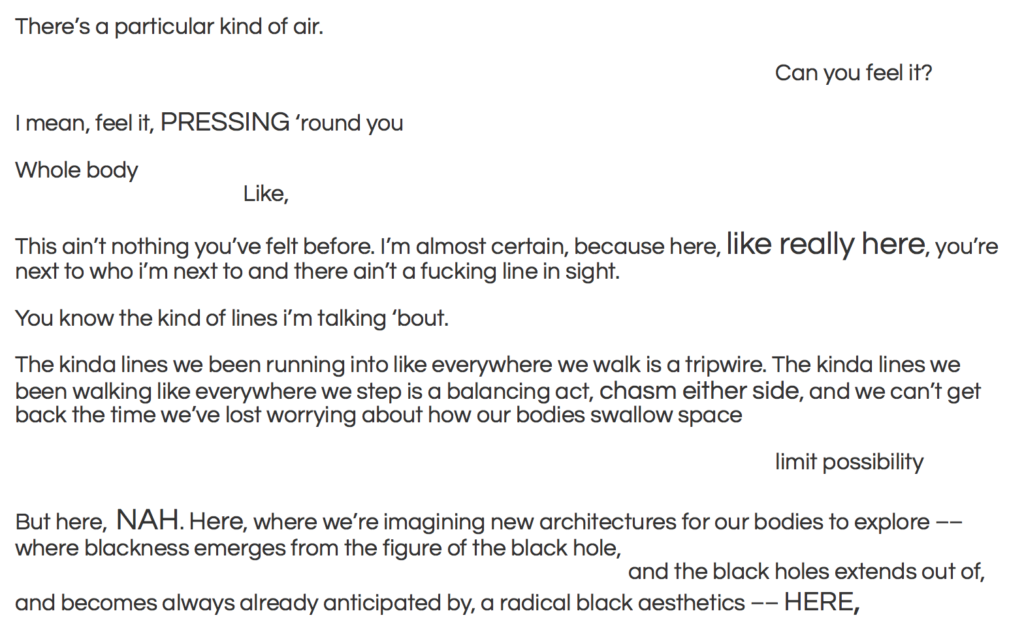

Rohan begins his poem, entitled Fracturing the Horizon: a Poetics of the Black Hole, by setting the scene:

Throughout his performance, Rohan circles the sculpture, rearranging and reading from the chorus of black music stands. Now and then a disembodied voice—that of the writer Jamilah Malika Abu-Bakare—emerges from speakers overhead to recite quotations from pivotal texts on Blackness and black holes.

Rohan’s citations amount to a veritable syllabus on Black aesthetics—his poem borrows texts from pillars of radical Black thought like Franz Fanon, Fred Moten, Jared Sexton, as well as scholars in the field of astrophysics. He invokes so many well-known lines that it become difficult to discern where his voice begins and the quotations end. Rohan speaks fluently and rhythmically, and his skill as a poet shines. He delivers so much information, yet it feels important to recognize every word, hold it in your mouth and speak it back, as if to say, “I understand.” But this approach is exhausting—I cannot keep up with all his references, and they all seem equally urgent. I realized later, after speaking with Rohan about the work, that I had incorrectly approached his performance with the goal of comprehending his words. I had tried to follow a line of thinking, rather than allowing myself to be encompassed by the experience of his voice filling the ballroom.

Rohan means for his performance to be experiential, not didactic—he tells me that he considers his poems “architecture,” and hopes that “when you read them, you become spatially reconfigured. You enter the space that the poem creates, and upon entering it the body changes its relationship to space.”

Rohan’s work is indebted to Afro-pessimism, a critical framework that considers our contemporary world as shaped by the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. For Rohan, this means taking the Door of No Return—a site on Gorée Island, off the coast of what is now Senegal, through which enslaved Africans passed before being transported to Europe and the Americas—as a starting position. This brings up a question that all three artists address in different ways: when is blackness simply a color and when is it a signifier for those people coded as black? “I move in a similar way as Nneka,” Rohan clarifies, “but I am not thinking about blackness as identity. I am thinking about blackness as position.”

He elaborates:

When I’m talking about ‘Blackness,’ I’m grappling with that history and its link to the Door of No Return. If the Door of No Return is a portal into modernity, what could be the portal or doorway that similarly transports us to another place? And that other place not being another world, or outer space, but that other space is here. What are the conditions and what are the doorways that need to be created, that move us from here to the next place? How do we get out of modernity which is structured around slavery, capitalism, greed, and individuality?

From this Afro-pessimist position, the black hole becomes a powerful model for thinking of alternative futures for all bodies. Rohan says, “I am thinking of the black hole as bringing things together to a singularity, but that singularity is also figured by a multiplicity and by a reconfiguration of space and time. When you get into a black hole, space and time become flipped, you know, so I am interested in that. A complete change in how we understand the world happens in the black hole.”

The title of this essay comes from a slip-of-the-tongue that Nneka Kai made during our studio visit.

Nneka Kai is an interdisciplinary artist from Atlanta, Georgia. Her work explores quotidian gestures of black female performance through line and hair, rooted in historical textiles processes, such as plaiting, coiling, embroidery and knotting. She received her Masters in Fine Art from The Art Institute of Chicago in Fiber & Material Studies. There, she was a Research Assistant at the Textiles Resource Center and a finalist for the SAIC Graduate Fellowship. Kai was featured in Local Stories in Voyage Chicago. She also holds a BFA with a concentration in Textiles from Georgia State University. Kai had a solo exhibition at Material Gallery in Chicago and has shown in Atlanta and North Carolina.

Rohan Ayinde is a Chicago based artist, writer and curator. A recent Masters graduate from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago he is the recipient of the New Artist Society Scholarship and The MA Visual and Critical Studies Graduate Fellowship Award. His interdisciplinary work is centered around creating “otherwise” potentials (Ashon Crawley), and in so doing breaking down and simultaneously reconfiguring the ideological architectures that shape our daily and generational lives. Most often the landscapes he explores are rooted in questions about quantum physics, black radical aesthetics and architecture. Rohan is a 2020 Curatorial Fellow with ACRE and has work forthcoming in a publication by Green Lantern Press. He has been featured in Dazed, Gal-Dem Magazine and The Guardian and has worked with VICE, LUSH and The San Francisco Chronicle among others.

Unyimeabasi Udoh works across various media — including textiles, prints, artist’s books, and computer games — in an attempt to bring to light and make peace with the void. Their work centers on surface and absence, text as image, redaction, redundancy, and the color black. They received an MFA in Visual Communication Design from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

- Adrienne Edwards, Blackness in Abstraction (New York: Pace, 2016), 10.

- Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation (Ann Arbor: Univ. of Michigan Press, 1997), 190.

- Jared Sexton, “All Black Everything,” E-flux, no. 79 (February 2017): https://www.e-flux.com/journal/79/94158/all-black-everything/.

- Fred Wilson, in Judith Barry et al., “Serving Institutions,” October 80 (Spring 1997): 120.

- Fred Wilson, “Structures,” Art21 video, 12:48, September 30, 2005, https://art21.org/watch/art-in-the-twenty-first-century/s3/fred-wilson-in-structures-segment/.