Not All Skin Folk Are Kin Folk: Why No Criticism for Virgil Abloh’s First Solo Show?

by Rashayla Marie Brown

The idea of speaking to and for Black people outside an institution appears to be the primary motivation behind Virgil Abloh’s first solo exhibition in the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, entitled “Figures of Speech.” Besides the press in the New York Times about Abloh’s meteoric fashion career and a cursory review of the exhibit in Architect’s Newspaper, we have not had any meaningful criticism that contextualizes Abloh’s contributions, how exactly his collaborations developed, and what the actual impact of his design is on issues of racial representation in the art and design fields.

Yet, there is an alternative public sphere of criticism that registers African-American vernacular as primary and not outside of institutions, contrary to the exhibit’s claim. Like Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s concept of the Undercommons, this subcultural sphere operates in common social spaces face-to-face—clubs, buses, after school—and are very much bound by institutional engagement. Riding a bus in Chicago will afford you more opportunities to critically engage with some Black art than any published criticism, if one is interested in talking to Black people in real life, not in theoretical tropes that position them as outsiders.

While riding the 12 bus westward, I overheard Chicago student and member of Young Chicago Authors, Jay Post, in conversation with a friend about the Abloh exhibition. At one point, he went silent. I turned around to see he had twisted his mouth to the side in suspicion, “Man, he claimed to be representing us, but instead he just gave us a big ass billboard.” What Post refers to is the blank, black billboard replica near the front hall of the exhibition with graffiti letters painted sparsely and ironically on its verso side. Publishing anything other than a glowing positive review of the first solo exhibition of a well-loved, hometown public figure will undoubtedly invite discomfort, the kind of discomfort represented by Post’s facial expression.

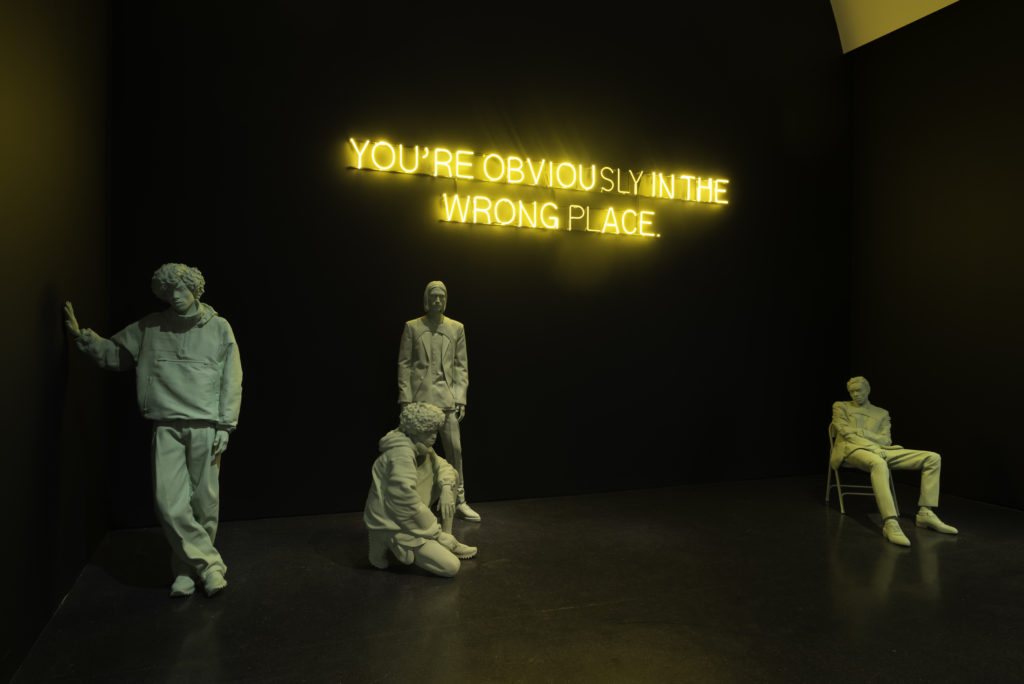

The MCA’s wall didactics, the incorporation of Black youth streetwear culture in Abloh’s graffiti appropriative aesthetic, and the subject matter of Black inclusion through afro-haired mannequins all lend themselves very well to an argument that this show is for Chicago’s Black youth. However, it insults their critical faculties through sloppy inclusion of ironic quips on billboard paintings that claim to be inspired by Duchamp, yet reinforce the exact artist-aura that Duchamp attempted to destabilize. Where Instagram celebrity status has produced a new cultural producer hell-bent on monetizing time and false relationships, Abloh’s in-person engagements are more important than the artwork itself, a conundrum touched upon by the numerous events and sites that occasion the show.

With the exhibition’s entrance flanked between the vinyl lettering “Tourist” and “Purist,” the majority of the work relies on well-worn, outdated, and ironic tropes in the service of representational politics, including a red video projection with the vinyl text “Blue” cheekily installed in front of it. The invitation to “question everything”—which is also the title of and text on a black flag blowing in the courtyard of the MCA—begs the question, who is this show actually for? Abloh’s career is almost single-handedly owed to his “insider” status through longtime collaborator, Kanye West. In a post-Kanye hip-hop era, where West has alienated himself from his fanbase through conservative political rants, we can assume this is for the wealthy insider who longingly presses his face against the glass wishing to be outside. The exhibition makes grand claims that Abloh critiques advertising while also selling a $4500 handbag in the gift-shop-as-artwork adjacent to it. “Insider” and “outsider” would have been more useful for the entrance vinyl framing Abloh’s influence than the “Tourist” and “Purist” offered.

While attending the Wakandacon—an annual conference in tribute to Black comics, urban art, and other types of art that would rarely find their place in a museum—I asked a group of panelists for Mike Stidham’s BlurdDotRadio show how they felt about the exhibition. The panelist Rhymefest, also a past collaborator of West’s (who was among the first to publicly comment on his mental health), commented that “not all skin folk are kin folk.” This is a common vernacular expression spoken by Black Americans that implies that, even if a person shares your racial identity, it doesn’t mean that they are part of your community.

The exhibition makes sure to note the frequent collaborations with West, but it falls short of encapsulating how—and why—the fashion world has established Abloh’s oeuvre apart from West’s to co-opt it for high-fashion, predominantly White and wealthy consumption. Abloh’s work does what a crossover artist in the music industry often does and what Rhymefest’s vernacular expression refers to—peddling stereotypes for privileged consumption, while claiming without evidence, to uplift a disenfranchised group. This type of work from the subaltern corners of the art and design worlds appears to the uninitiated to be exactly like what it claims. However, in practice, rarely are the voices of this self-assigned public actually consulted in decision-making or leadership beyond the symbolic. Successful inclusion endeavors are always more intimate than museums admit and cannot be exploited easily for public, thematic exhibitions.

More and more in a fight for contemporary relevance, museums are reaching for opportunities to reach publics that vibrantly persist in discourse beyond their bland, white walls. This essay should not have been the first essay of serious criticism about this exhibition that does more than chart Abloh’s relationships. With its poorly designed layout, the under-curated racks of minimalist and unflattering clothing shapes that no average-sized human could wear fashionably, and a row of Nike sneakers bound for the sweatshop alongside bland paintings of billboard text, this review cannot possibly imagine the exhibition as “one of our own,” but as more than a publicity stunt for social media. I can think of several artists who actually have a presence in the city, participate in programs with Black youth, and make streetwear or urban art who could have done more with this opportunity. Unfortunately, if an institutional exhibition is the goal, these artists do not sell overpriced clothing to White people, have White partners, or alliances with (male) Chicago pop stars.

This problem is a common one that the private-public sphere of Black life in America—the double consciousness that W.E.B. DuBois articulated to us over one-hundred years ago. We all know Black people who claim publicly like they do not eat fried chicken in White company only to devour it behind closed doors, so they don’t invite scrutiny of looking like a stereotype or Uncle Tom. Abloh’s work complains about White supremacy in fashion and then sell products designed to uphold the financial and material oppression of one group over another through collaborating with companies such as Nike and Louis Vuitton. This is the fashion equivalent of saying you don’t eat Harold’s, while we can see the grease dripping down your chin.

Virgil Abloh: “Figures of Speech” runs at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, until September 29, 2019.