A thousand kisses deep

by Casey Carsel

Leonard Cohen: A Crack in Everything // The Jewish Museum

In its didactic’s promise, Leonard Cohen: A Crack in Everything at The Jewish Museum in New York, explores Cohen’s life and work, his inspiration upon other artists, ‘how [Cohen] entered the cultural conversation, how [he] cut deep into the marrow of the body politic.’ However, such a massive promise is sparsely fulfilled in an exhibition that clings so close to its source material as it becomes difficult to discern a cultural conversation or body politic wider than what Cohen’s lyrics and poetry already provide.

A Crack in Everything traveled to The Jewish Museum from the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, which commissioned over 40 visual artists, filmmakers, musicians, and performers to ‘revisit Cohen’s magnificent oeuvre.’ Condensed and compacted at the NYC-based museum, the iteration features around a dozen installations. Situated across three floors, this great opportunity to investigate the specifics of how and why Cohen is relevant to our present moment—or even his own moment for that matter—is passed up in favor of a repetitive and general insistence on the artist’s depth.

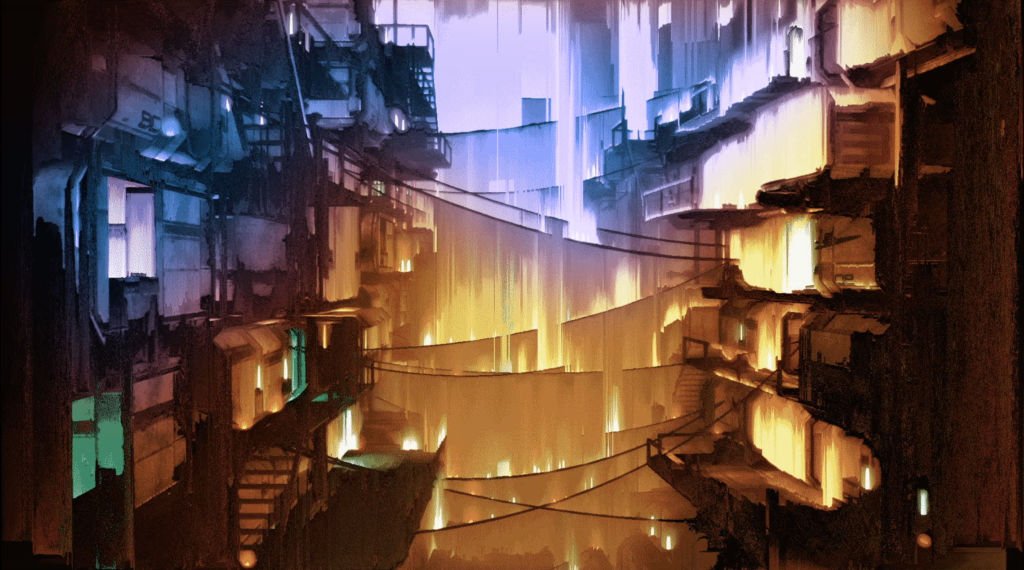

Photo: © Frederick Charles.

The first floor gives much of its space to works contextualizing Cohen’s life and oeuvre, in part to catch up the (few, when I attended) younger viewers for whom Cohen may not have been a lifelong staple. One such contextualizing piece is George Fok’s Passing Through (2017). By far the most popular piece, with a room so full viewers cram in at the doorways, the immersive three-wall video presents Cohen’s life and work through a medley of archival footage. The lucky or well-timed viewer can sit on a bench or beanbag chair, with the latter harking back to the original 1960s bedroom setting in which many long-time fans first listened to Cohen. In the room next door, Kara Blake’s smaller documentary video, The Offerings (2017), is based on interview footage and acts as another loving immersion into the life of Cohen as a significant cultural figure.

Two particularly derivative (a word used in the didactic for one of the works without any sense of self-criticism) artistic responses to Cohen are Christophe Chassol’s Cuba in Cohen (2017)—a musical remix of Cohen’s 1964 poem The Only Tourist in Havana turns His Thoughts Homeward—and Kota Ezawa’s Cohen 21 (2017)—an animation of the first few minutes of the 1965 documentary Ladies and Gentlemen… Mr. Leonard Cohen. Across the hall, Taryn Simon’s The New York Times, Friday, November 11, 2016 presents the The New York Times’ cover from the day Cohen’s obituary was printed—four days after Cohen’s death and three days after Trump was elected President. The work whispers of expanding Cohen’s presence into a wider discursive sphere, but goes no further than chronological coincidence, shying away from more tangible critical discussion around how a musician can affect and be affected by his times, or anything other than the preoccupations of a day shortly after Cohen’s death.

Next door, in Ari Folman’s Depression Chamber (2017) visitors individually enter a room and lie down. Their image is then projected onto the ceiling, and Cohen’s Famous Blue Raincoat plays, the lyrics transforming into various symbols—such as an old man and a Jewish gravestone—that congregate around the viewer’s body, shrouding the viewer. To experience this shrouding is deeply affecting, though somewhat disappointing for my companion, whose darker skin tone almost completely disappeared in the projection of their image. The experience speaks well to the emotion and religious themes of Cohen’s work. Perhaps the piece would have been more effective and less karaoke-like had Folman dared to abstract the song itself further.

The second floor centers Daily Tous Les Jours’ I Heard There Was a Secret Chord (2018), a room of hanging microphones in which visitors are invited to hum along to a recorded set of other voices humming Hallelujah. Accompanying the work is a numerical display that indicates how many people around the world are listening to the song, the installation adjusting the number of voices accordingly. The call to a sense of worldwide connection theoretically feels over-sentimental in the hyped language of the didactic, but put to a song like Hallelujah, with its associations and genuine affect, the sentiment feels touching.

Jon Rafman’s Legendary Reality (2017) takes one of the furthest journeys away from its source material, though still not straying far. A non-linear science-fiction essay film, it constantly quotes Cohen, but in a surreal new context. Another work that wanders from an explicit portrait of Cohen is Tacita Dean’s Ear on a worm (2017), a small video on the second floor—tucked above a doorway—of a bird singing. Though punning on Cohen’s song Bird on the Wire, Ear on a worm is the first work within which I do not explicitly encounter Cohen’s words, tune, voice, or face. Instead I am given the opportunity to see the bird through the lens of Cohen, perhaps impossible without the works that lead up to it, but also what I had been waiting for.

The final piece of the exhibition is tucked away, alone and almost marginalia-like, on the third floor. A series of recent Cohen song covers set to extended and slow Josef Albers-esque videos of morphing rectangles of color, it presents a development in Cohen’s legacy while remaining largely adoring and—with beanbags again scattered across the ground—nostalgic rather than critically expansive.

Across the three floors of The Jewish Museum, I learnt a good deal about the life of an influential figure. But rather than having the artworks narrate or illustrate this life, much more potent and affecting would have been an expansive range of artistic reactions and extensions that contribute to culture instead of repeating it. If the show’s intentions were to cling so closely to the source material, the commissioned artists could have stayed home. As it is, the exhibition would benefit from seeing a further degree of digression not as a distraction but as a path to a true illumination of Cohen’s lasting influence.

Leonard Cohen: A Crack in Everything runs at The Jewish Museum until September 8, 2019. The exhibition then travels to Kunstforeningen GL STRAND and Nikolaj Kunsthal, Copenhagen, Denmark from October 23, 2019 – March 8, 2020, and the Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco from September 17, 2020 – January 3, 2021.