Potent Pussy: Judy Chicago

by Natalie Hegert

“It would be ridiculous to say that there’s been no change,” Judy Chicago intones with we’ve-been-through-this-before fatigue, “…but you know I can still open an art magazine and see all male shows. I don’t fucking believe it.” Chicago and I spoke over the phone just weeks after the Women’s March on Washington seared the national consciousness with images of teeming crowds in pink pussy hats. She was “thrilled” about the demonstrations, but warned against focusing so much anger and attention on individuals like Donald Trump. “You know, this is not about a person,” she says, “This is about a structural, global system. And the art world is a picture of it.” The institutions that prop up the patriarchy are the product of hundreds and hundreds of years of consolidated power, and dismantling them involves more than the overthrow of one misogynist president (or museum president, or gallery owner, or collector). For her, this is what feminism is about: “changing the global power structure.”

Judy Chicago’s outspoken attitude, landmark works, and impact on art history, should not be underestimated, but institutionally they continue to be. At 77 years of age, Chicago still has not had a full museum retrospective. The size of her monumental works, such as The Dinner Party (1974–79) and The Holocaust Project: From Darkness Into Light (1985–93), would require a major museum to step up, but so far, they have not.

Though the art world has experienced much change in the fifty years since Chicago began her career, change comes slowly. This October, the Brooklyn Museum will mount an exhibition of studies, preparatory, and research materials from The Dinner Party, marking the first time that serious art scholarship will address the creation of Chicago’s watershed feminist artwork.

However, Chicago’s work is not all feminist monuments and overturning the patriarchy. In September 2017, the artist will be showing the paintings and prints of cats she produced across her career, in a forthcoming exhibition entitled Judy Chicago’s Pussies at Jessica Silverman Gallery in San Francisco. We spent a good deal of our conversation comparing notes about feline personality traits and getting interrupted by our cats’ antics, while we carried on a frank discussion of feminism and intersectionality, craft and kitsch, and the role of research in her work.

NATALIE HEGERT: You have incorporated vaginal imagery in your work since the 1970s. What was it like to see the sea of pink “pussy hats” and signs sporting female genitalia during the Women’s March—essentially, to see the vagina go mainstream, all over the world, in a way it never has before?

JUDY CHICAGO: This is a really big change from when I was a young artist, when any hint of gender in one’s art was just completely unacceptable. So I love it, this profusion of pussy; I think it is hilarious and wonderful: pussy in your face! On the other hand, I have to say, I want to see women artists go beyond concerns for self, and the young generation seems to be all about me.

NH: The feminist movement has gotten flack for trying to unify all women under one banner, and in so doing, marginalizing the experiences and struggles of women of color, trans women, and queer women. You have stated before that you are looking to find ways to use the female experience as a way to express the universal. Has your view of the universal changed in light of the calls for the recognition of intersectionality within feminism? How have you addressed that in your work?

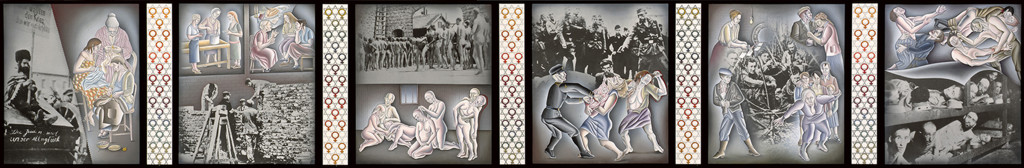

JC: Young feminist theorists like to fantasize that feminist artists of my generation were not conscious of intersectional issues, but that is totally not true. One of the reasons I selected Sojourner Truth for The Dinner Party table was because she was one of the first women to talk about the intersection of gender and race. So, I have always—and certainly as my work developed—explored those issues. For example, in the Holocaust Project, there is a work entitled Double Jeopardy (1992), which looks at women’s experiences in the Holocaust, and deals with the intersection between anti-Semitism and antifeminism; how that defined Jewish women’s experiences.

If you talk about lack of power, victimization, marginalization, discrimination—the things women have experienced all over the planet in various forms—informed as it is by the intersectionality of where you live, what class you are, what race you are, you could say the female experience is more universal that the white, male, Eurocentric experience, right? The idea that a privileged, small class of artists and writers has been exploring and creating images and stories that are universal is actually quite ludicrous.

NH: Let’s talk pussy. Your upcoming show at Jessica Silverman Gallery, entitled Judy Chicago’s Pussies, looks like it will feature your cat paintings from 1999–2004.

JC: Since my career turned eastward, as a result of the permanent housing of The Dinner Party at the Brooklyn Museum, I have had tons of shows in New York, in LA, and in Europe—but in the Bay Area and Chicago (if they think of me at all) they think of me in terms of that work. So Jessica [Silverman] tells me she wants to show Kitty City (1999–2004), but people are going to have no context for it. But then, when we were looking in my flat files and my archives, I realized that dating back to the 1970s, there has been an intersection between my interest in developing images of female agency, like in The Dinner Party and my earlier vaginal work, and my interest in cats. In the ‘70s, there is a series of prints I did called Potent Pussy: Homage to Lamont. Lamont was my cat at the time, who died, with whom I had been besotted. So, we started with that, and traced a whole arc of work where there was an overlap between pussies and pussy.

NH: Do you see that as a kind of symbolic relationship?

JC: Well, I do not think so—you know, I have lived with cats since I was twenty-one. The first time I started drawing my cats was in 1993–94 (by that time I had come back to representation). And then I got really interested, like I do, and started doing a lot research about cats. Then I did Kitty City, as a ‘Book of Hours’, based on medieval books of devotion, which actually took 5 years, because you know cats do not exactly pose. It ended up being a really long and fascinating project, because I learned all this stuff about cats! I will give you one little fact: the hypothalamus is the seat of emotion in human beings. Well, it turns out that the hypothalamus in humans and cats is really alike. So there is a kind of an emotional similarity between cats and humans.

NH: Your work has continually challenged art world values—for instance in your incorporation of “craft” mediums like ceramics and needlepoint in The Dinner Party, paintings of cats, or of any domestic animal, occupy a sort of “kitsch” place in art. Is this part of a longstanding project to question the assumptions of value in art?

JC: I do not think like that—I just don’t. I believe that all human experience has the potential for meaningful content. The same with all techniques. It is popular to say that I elevated women’s craft into high art. But, not only had I apprenticed myself to china painters and learned about the history of needlework the decade before—I had gone to autobody school, and had apprenticed myself to boat builders when I wanted to do fiberglass. It is just that those different techniques have been gendered by the historic framework of art. And I just do not think like that. In The Dinner Party, people always talk about women’s craft, but one of the primary people in The Dinner Party studio was an industrial designer named Ken Gilliam. His skills in industrial design underpinned all of the systems in The Dinner Party. But nobody ever talks about that, because they want my work to fit into the categories that have been established, and it just does not fit. And I do not fit. Like, what do you mean, kitsch? Hilton Kramer called The Dinner Party kitsch! Is that how it is viewed now?

NH: One area where I do not think your work gets enough credit is in your massive undertakings of research—The Dinner Party and The Holocaust Project both involved a staggering amount. Can you speak a bit to the role of research in your work?

JC: Yes—though I do not fit in terms of how a lot of artists make art. For most of my career, I was not focused on my career, the market, or money. I come from a generation before the international art market. We never thought we would make money from our work. What was important to me was making a contribution. I also believe, and have operated from the idea, that art is discovery. That is just how I operate—I educate myself, apprentice myself, study, and look, and then at a certain point I begin to formulate images based on what I have learned and what I have discovered. For me, that is just how I make art.

JUDY CHICAGO is an artist, author, educator, and humanist whose work and life are models for an enlarged definition of art, an expanded role for the artist, and women’s rights to freedom of expression. Chicago is most well-known for her role in creating a Feminist art and art education program in California during the early 1970s, and for her monumental work The Dinner Party, executed between 1974–1979. Over the subsequent decades, Chicago has approached a variety of subjects in a range of media, including the Birth Project, PowerPlay; and the Holocaust Project: From Darkness into Light. Chicago’s work has been exhibited widely in the United States and internationally. Her upcoming exhibition, Judy Chicago’s Pussies, will open at Jessica Silverman Gallery in San Francisco in September of 2017.