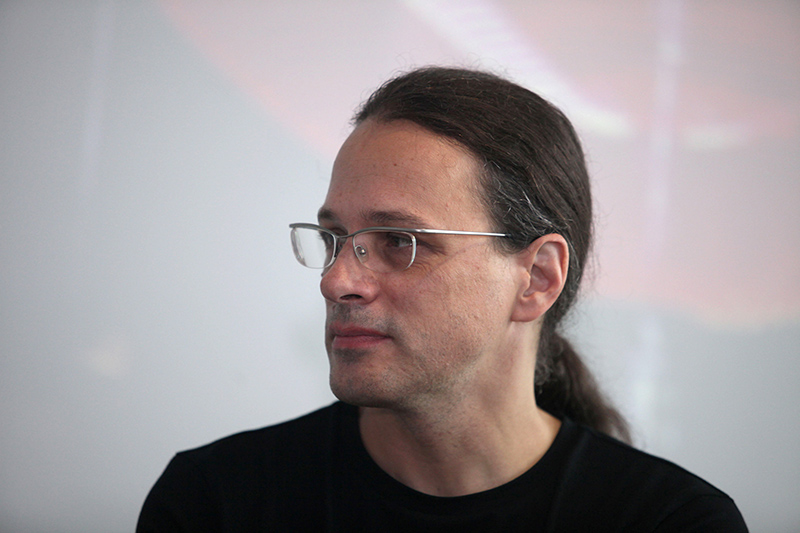

Profile of the Curator: Gerfried Stocker

by Dominique Moulon

Gerfried Stocker has been the Artistic Director of the Ars Electronica Center in Linz since its opening on the north bank of the Danube in 1996. He co-manages the festival of the same name, which is dedicated to art, technology, and society – below is a transcript of our conversation, mainly about aspirations for a “Museum of the Future,” methods of documentation vs. notation, and the importance of a physical space that houses sometimes non-physical artifacts of new media artwork.

Dominique Moulon: Isn’t a project to create a “Museum of the Future” doomed to fail?

Gerfried Stocker: Of course, if you take it literally, it would be – but choosing this subtitle “Museum of the Future” was more of a strategic decision for me. When we opened the Ars Electronica Center – the topics, the content of our exhibitions, and our activities – was far more complicated or hard to understand or even unimaginable to most people. So, if we had called it “Ars Electronica Center for Art & Technology,” it would have always taken us probably a full five minutes to explain to them that it is not something dangerous or weird, not some sophisticated scientist or artist or whatever, but that it really is a public institution, like a museum. The only thing you have to do is go there, enter the building, and then somebody takes you on a tour and shows you all the interesting things. “Museum” is the word that indicates that to people, not so much the content of the building in our case, but more how to interface with our institution.

The idea behind this was always also to see the Ars Electronica Center as a kind of laboratory where we can find out and work out how a museum can work in the future. It is not a museum that is exhibiting the future, but more the idea that this is a prototype of how a museum can function in the future; how the tasks of a museum can continue in this world of Internet, considering that in 1995–96, there were still many visions and ideas that perhaps a museum that has an actual building was already a matter of the past. Nowadays, we have a much clearer understanding of the incredible asset of a physical building in a real space, in a real city, with a real audience and real objects – it is extremely important. Then again, with interactive media are becoming more and more important, how can you make this “museum of the future” in terms of the way you communicate with people, how you exhibit, how you present things?

DM: Does the use of technologies in the field of art encourage rereading, or even reactivating historical practices?

GS: Actually, I would say that there are three different phases in the development, or evolution of new technology. One is that when we have a new medium, we only have the practices that we used in the old medium as our repository to try out what the new medium can do. You can see this throughout history from cinema to television and beyond, it’s always the same thing. At the moment, you use the methods, the practices that you know from your existing tools, or media and technologies, to try out, challenge, and explore the new one. Then comes a phase where new experiments come up, with a big excitement, because suddenly we think “now we have found the new direction.” Then always comes a third period, where people are a little bit disappointed that new, very new, or even super new ideas are maybe not so super new again, and that even with the new technology, you face similar problems in the end. So then, a period of rethinking happens. In this simplified model, it becomes more interesting, because you already know some of the deficiencies and impossibilities of this new technology, and then you have to deliberately go back and think: what did we forget, what did we leave behind when we rushed into this new digital age? Then suddenly there’s a super new exciting period of rediscovering history and rediscovering former things that have been left behind in terms of using the medium and exploring it. This is the really interesting thing because it is sort of finalizing this step. In this very simplified model, it needs these three elements.

DM: Considering variable media artworks, can the online archives of their documentation, over time, even more important than the artworks themselves?

GS: Yes, definitely. This is something we could even improve, how to create the culture or knowledge of not just how to document, but how to notate media art. Documentation is, in any case, a graveyard. What I’m really interested in is if we’re able to develop a notion of difference between documenting and notating, as it is compared to in music. In music, we have several thousand years of experience of how to keep time-based art (such as music) alive by educating generation after generation of professional re-players, professional re-interpreters, like conductors, so that music has survived through a continuous process of revival.

I would even very strictly here deny the use of the word “documentation,” because no matter who does the documenting, it implies that you’re saying your subject is a finished thing. What the artist needs to write instead is a type of instruction for the future. I don’t know what the position in charge of this responsibility would be called, but I am pretty sure that in at least fifty years, we will have a new job title that is not just “restorer.” It will be more like the “conductor,” people who are recompiling, reinterpreting this work. And they will need instructions. The problem is that even if we have a perfect description of Bill Viola’s piece, in 50 years there will be almost no chance to have the same type of equipment. Somebody has to make a choice to always just show the video of the origin as a documentary, or to move the work into new media. And it will be a radically different media – the only way for this work to survive is not by documenting, but by notating it in history, and instructing.

DM: Regarding the themes of your festival – art, technology and society – the word “society” appears to have become the most important keyword in that series in terms of structuring the activities at Ars Electronica.

GS: Yes, definitely. Of course, in the beginning of Ars Electronica there was a big focus on the technology because it was the new element – and everybody was excited, including the artists. But this fondness for technology was often disregarded as precisely that – a mere fondness for technology. The really important work of that time was not being excited to play with technology, but the first chance to find out what was possible due to the technology. By dealing with the possibilities of technology, artists in this period really opened this realm to society – in my sense; they had a very political agenda, working on taking these technologies out of the realm of industry and bringing them into the realm of the public.

The great set-up of Ars Electronica was done in 1979 and still remains – the festival evolved alongside how technical culture and technology itself evolved. It was in the mid-1990s when my team started to work here, when the World Wide Web and when the Internet suddenly became a reality to everybody. We always wondered if the future had reversed its direction: instead of being almost ahead of us, suddenly it was as if the future were coming toward us. We were in the middle of this, when all the things that were being promised or speculated 10 years ago were suddenly happening. And so, more and more, we had to look at the social impact. There was also a demand to talk about this development with general audiences, a demand from companies, enterprises that also wanted to get closer to this, so there were suddenly much more elements in the mission of Ars Electronica. This is why since the mid-’90s, the societal aspect has become the important, almost predominant part of Ars Electronica’s activities.

DM: Do you think that a media artwork must be presentable within a white cube, as Christiane Paul suggested in her 2008 book New Media in the White Cube and Beyond?

GS: To seriously answer this, we would need to have a very long discussion about what media artwork means. It’s like if you say “animal”, why don’t we talk about a crocodile, an elephant, or a mosquito? There are totally different kinds of media art. Of course, there are common elements that define those areas as media art, but when it comes to the question of how to present it, and where to present it, the answers are totally different. And the cage that could accommodate a crocodile might not accommodate an elephant or a mosquito. So there is media artwork that fits perfectly into the white cube, because of the intention of the artist. But there is also plenty of other media art that does not fit in the white cube, and this is already the wrong saying. Perhaps better phrased, it does not belong in the white cube.

I think we still have a wrong understanding of what media art really is by still using the Pompidou, the MoMA, the Tate, and all those other institutions, as a kind of reference. Why should a media artist, besides the money, exclusively be interested at all in getting into these spaces? There are constantly new markets popping up, and I think media art is just on its way. I would actually argue that I much more often see white cube owners being desperate about how they can integrate media art, rather than the other way around.