In Conversation: Daniela Steinfeld

by Stephanie Cristello

If you are interested in the work of certain locally exhibited artists, you may look into their other exhibitions abroad. I first discovered VAN HORN‘s program in this way, through research I was doing for a review of Wendy White’s exhibition at ANDREW RAFACZ in September of last year. The program, which is pretty evenly half American, and half German – exhibiting artists such as White, Nicole Eisenman, and Andrea Bowers – is one that might be discovered more often in this way because of that. I was able to meet with the Director of VAN HORN, Daniela Steinfeld, during her brief stay in Chicago the week before last – below is a redacted text of our conversation; on her transition from being a gallery artist to a commercial gallerist, the differences between American vs. European attitudes on market and gender, and the rare, but special chance of encountering unknown, or yet undiscovered work.

Stephanie Cristello: It makes sense to start with defining your position, since you transitioned worlds within your careers, as an artist and gallerist. How did you manage both?

Daniela Steinfeld: Well, actually – I made the out to become a full-fledged gallerist a few years ago. I do not think it is possible to have a career as an artist or a gallerist professionally at the same time. It’s absolutely impossible; to do both would mean that you are not able to take either seriously. There are very few examples of figures that do this, and they always choose one side or the other in the end. I have found that working with the artists I have in my program, installing their exhibitions and selecting the work that will be on view, is my way of entering the dialogue I had as an artist myself. My position as an artist was also an advantage, but I am not sure it ever helped me in the commercial aspect. Once I entered that world, things changed. My background certainly helped with my viewpoint, and the quality of the exhibitions, because I understood how the work was produced.

SC: How do you find your artists? In the beginning, was it through your connections as an artist?

DS: I had a successful career as an artist – it was not from a lack that I started the gallery. It was really due to a genuine interest, a kind of enlarging myself, an extension of what I was doing. I found that being an artist was somewhat limiting, in the sense that there is a limit to what you can do – my vision, my ideas – and I am only one person. I could do whatever I wanted; I had more freedom then than as a gallerist. But, on the other hand, working closely with other artists opens up worlds that I could never access just by myself. There is no limit as a gallerist. The first two exhibitions I had at VAN HORN, back when it was an artists’ space, were solo exhibitions of R. Crumb, and Rudolph Steiner – between those two very, very diverse aspects of how you can do something like present art [to a public], that was my statement. It was since developed into what is now a more contemporary program, these exhibitions were followed by an exhibition of four works I chose by Nicole Eisenman back in 2002, and she will actually be showing again this fall. It is our ten-year anniversary!

SC: Freedom is an interesting word to think about.

DS: Yes, absolutely. In the very beginning I started by having a list, which included all the artists I really loved, and knew I wanted to work with. A lot of this list ended up coming true – Crumb and Eisenman were on it, but also Reinhard Mucha who I later showed in ‘09, and Wols accompanying Vanessa Conte in ’08 – it was a mixture of those who were incredibly well known, and others who had been under-represented. Funnily, the exhibitions I did led to a kind of renaissance for these artists. I am showing these artists through their projects at the space, and often-unexpected things come from that exposure. For the artists I am regularly working with, that I represent, we started from scratch. And although I am showing some artists like Wendy White, who had gallery shows before –

SC: But was not well known in Düsseldorf I’m sure –

DS: Definitely. She really deserved a lot of success and attention, and that had not happened for her yet in Europe. Many of the other artists I showed, such as Andrea Bowers, were artists I knew through myself being an artist – we had the same gallery in New York. Eisenman, also, was because I saw a show of hers during one of my first visits to New York in ’95, at Jack Tilton. And it was so super good, so great – that she got on my list! I approached her and said that I was running this space, and Leo Koenig who she was working with and still is, supported that – just like Paul Morris supported my choice to show Crumb. So, from the very beginning, these doors were wide open. When you are an artist, and have an artist’s space, people love that and support you.

SC: Galleries are more willing to lend their work.

DS: Oh yes, easily. Everyone I approached agreed. It was super accessible when I was approaching them as an artist. The moment you turn into a commercial gallery, things change. It’s not that the doors are closed, but you have to find different doors. You are judged on very different levels. Also, me coming from the side of an artist, I did not understand all the boundaries involved in the beginning. For the first five years of VAN HORN being a gallery, I just acted like an artist, which was all I knew how to do.

SC: There is also a freedom in not knowing what those boundaries are also –

DS: Right. You tap into some problems that you did not even think existed; I was naïve in that way. I am not anymore! But this naïveté leads for you to pursue things that you would have otherwise been inhibited to think about.

SC: Were there any differences in pressure on the artists between the artist’s space model and the commercial model?

DS: There was always a lot of pressure. In the beginning after having my first year of exhibitions – Crumb, Steiner, Eisenman, back-to-back – there was this pressure to beat that line-up. The bar was set very high, what I experienced was that my artists wanted to do their best work for the space, and I am still encouraging this. From the start I made it clear that this was not an experimental space, or the field where you could just “play around a bit” – you come here with the best work you can do. I have really close ties with museums and institutions, so the pressure was never to only sell, but to be an artist that those organizations wanted in their collection, to be a part of history. You work until you die [laughs].

SC: There is no retirement for an artist!

DS: I fear not for gallerists either! The interesting thing is to see how these two paradigms will play out in the next few years. I know many gallerists who are struggling with this – of having a lot of commercial success with their artists, but lacking an engagement on a deeper, psychological level with the work. For me, it is an interesting question to ask how an over-the-top market, such as our current one, actually affects the market just below that tier, on the ground.

SC: How do you deal with that?

DS: I hardly deal with it at all thankfully – in Germany, there is a different mentality. Some of my collectors will buy at auction, but a lot of them want to buy from galleries, they want that personal contact and to support smaller businesses. If you want to not have a mainstream art scene all over the world, you have to feed your local markets. Things can be local and international – this is not a contradiction.

SC: Many of your artists are American; do you see yourself feeding an American-European exchange?

DS: You are right; my program is half American, and the other half German. It was not intentional – I am interested in artists from all over, but it just happened that way. Through my extended stays in the United States as an artist I have a relationship here, I travel at least twice a year here and that is how I get to meet artists. But I also see many of them online first, like White I found while I was browsing the Internet, and then follow up with a studio visit. I like Wendy’s work precisely because it is so American, I think she has an immense vitality because of that.

SC: The struggle spurns survival!

DS: But really, I think it is in her work. I am attracted to her work in the same way I am to all of the artists I represent – they do not belong to a school, and the work they are making is very essential. To define that further, it is just to say that it is a very singular way of working. It puts me at a disadvantage at the same time; belonging to a school of artists is often more successful. But I am so drawn to these individual fighters; they stay with their work.

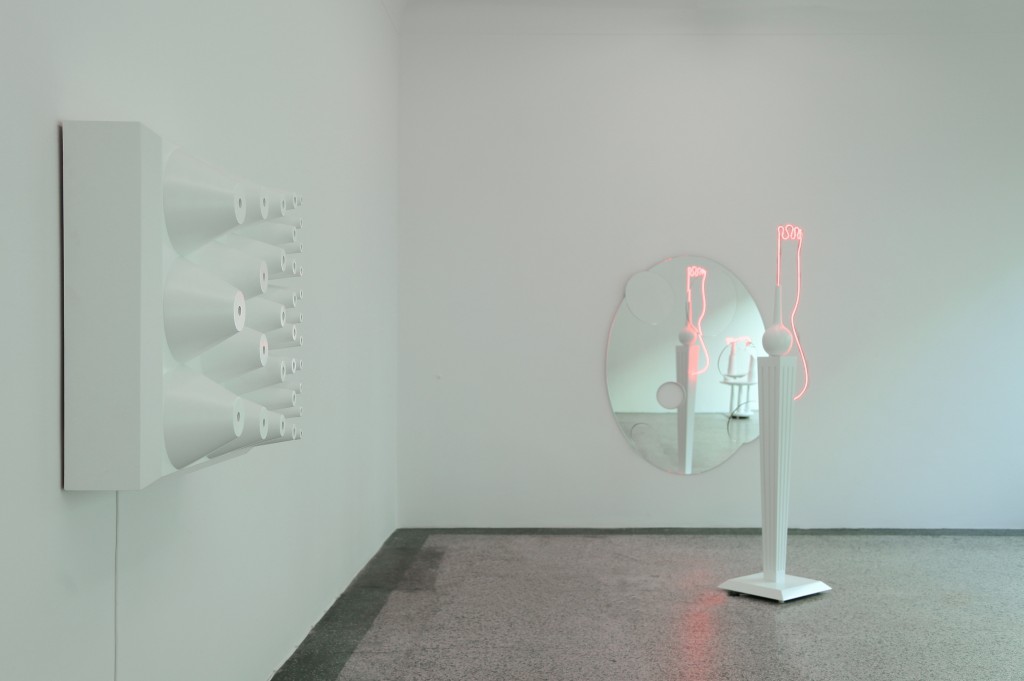

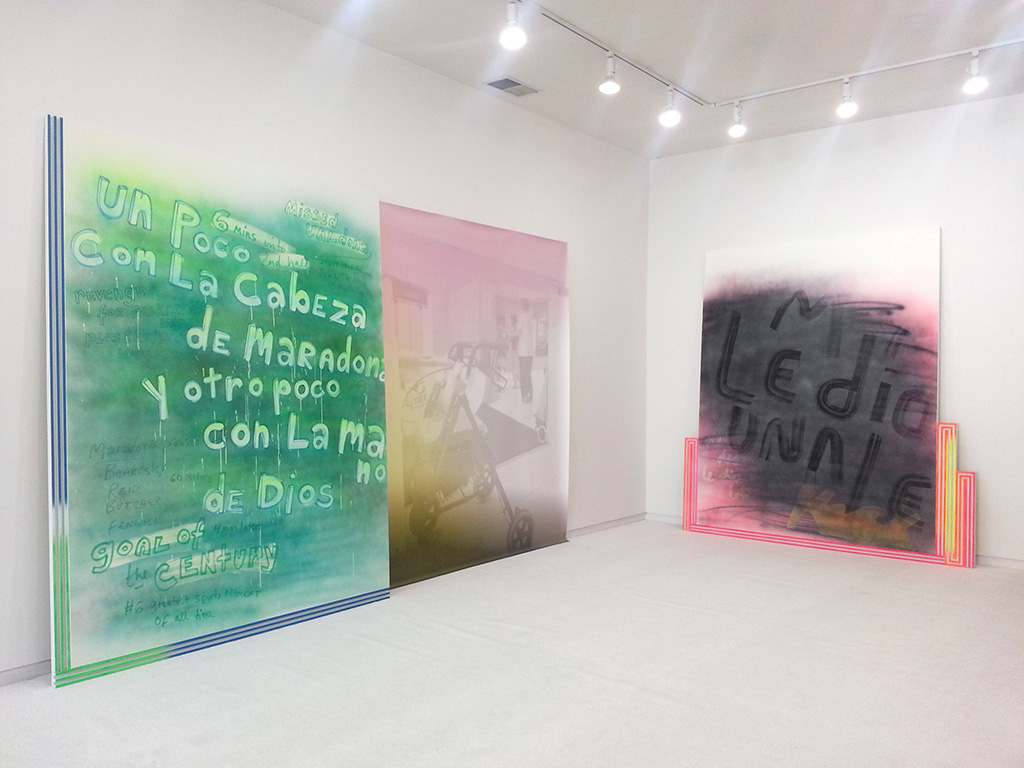

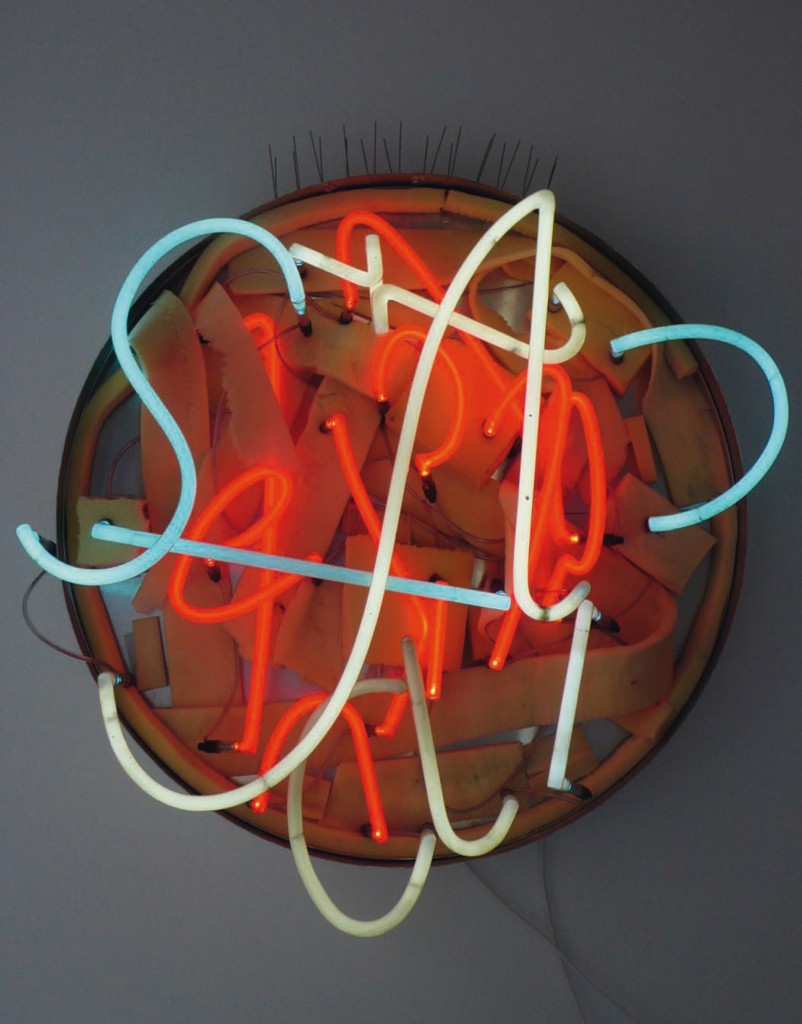

SC: Can we talk about your current exhibition, Chambre d’Amour? This is your first light installation at the space, correct? From what I have seen, it is very dependent on the light conditions of the atmosphere.

DS: Yes, the exhibition is very involved with light, and it has a certain charm when it is in the twilight – but it works throughout the day. It creates its own little space. This show has a very interesting backstory as well. There was another show planned for that time slot, but the exhibition didn’t happen – the artist just became a father and wasn’t able to finish the proposed work in time. He told me that about three weeks before the exhibition was supposed to open. I had planned to more or less extend the run of the current exhibition to cover that, but then an artist I had known very personally for a long time, Sigune Siévi, who lives in Berlin and studied in Düsseldorf, got in touch with me. She raised her children, who are now 16 and 18 alone, and during that time she did not seek any public attention for her work – I did not even know that she was still making work. But she was in secret. It was a pure coincidence that she approached me and said that she had been working on some things over the last couple years and wanted my critique. Everything that she showed me at that visit is on view in the exhibition now. It was amazing to me that somebody who was not a part of the art scene, someone who had not gone out and been a part of that world for so long (fifteen years!), was making such strong, and special contemporary work. It was like a gift. This exhibition belongs to the top five exhibitions I have ever done at the space.

SC: What are the other exhibitions that belong to that five?

DS: I sort of just made up that number, I could just have easily have said top ten – but I really think it was that first year, after that I had to ask myself: why continue?

SC: Because things like discovering Siévi can still happen?

DS: That is true. There needs to be someone who can discover this work and give it the attention it deserves – she is not a young, white, American male, and unfortunately that is still the standard that often gets shown. I am not showing women because they are women; I am showing women because they are good. Right now, more than half my program is artists who are also women, and I think they have a lot to say!

SC: Though, none of the female artists you show ever directly address their status as a woman in their work, which is really refreshing. In many ways it helps the conversation by not having it at all, because they have nothing to prove.

DS: No, they are just great artists. It was something that never occurred to me until after the fact – last year I showed almost exclusively female artists, but I didn’t give it a thought until the year was over and someone pointed it out. Who cares? I think we should be over that. They are just fucking great artists [laughs]! The artists I am showing are too good to be distinguished in that way, it is a reductive way of thinking. At the same time, this gender discussion is very American; we don’t have that as much. My own work reflected this discussion a lot, even though that was never what my work was about, but those reviews were always written in America. I feel like it is a big misunderstanding. But it is interesting that artists like White end up participating in this very “male” conversation with her work, but artists such as Jan Albers, who has an exhibition up in LA at 1301PE right now, is part of a discussion about craft and domesticity and so forth, because people read his name as if he were a woman. When people realize his gender, their whole perception of his work changes, which is insane to think about. We can’t say that the difference does not exist, of course, but it is just so crazy how much it influences these huge polarities and discrepancies in opinion on the work, over something that ultimately does not matter.

SC: This model for VAN HORN is a sustainable one for you, it seems – one that works for your artists first.

DS: Yes, and the hope is that it continues to grow in this way. I am fighting for an art world where this is all possible – striving for quality and not politics. We all have to live from our work.

Sigune Siévi, Chambre d’Amour, at VAN HORN runs through April 19, 2014.