Christopher Knowles: In a Word

by Joshua Michael Demaree

“All these are the days my friends and these are the days my friends.. It could get some wind for the sailboat. And it could get for it is. It could get the railroad for these workers. It could get for it is were. It could be a balloon. It could be Franky. It could be very fresh and clean.”Christopher Knowles

The above words are sampled from the libretto of Einstein on the Beach, an opera first staged in 1976 that has since become one of the most revered and mythic productions of modern art: it is marked as the welcoming of opera, the Gesamtkunstwerk, into the avant-garde. It’s influence is unending and its importance is staggering. At the time of it’s production—touted as a joint effort between theater director Robert Wilson, composer Philip Glass, and choreographer Lucinda Childs—much of Einstein on the Beach’s power, in my opinion, lies in its words, which partially came from Christopher Knowles, at the time an adolescent in upstate New York that had been diagnosed with brain damage.

For its fall exhibition, co-curators Anthony Elms and Hilton Als, theater critic for The New Yorker and author of White Girls, present at the Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania a retrospective of Knowles’s work. Known as a poet and a painter, his adherence to mid-century multimedia artistry is clear, making any clear medium designation a futile exercise. Like his collaborators for Einstein, Knowles work fluidly muddles the lines between the visual, aural, and performative arts. Spanning nearly forty years, the show provides not only a comprehensive study of one of contemporary art’s most fascinating players, but also a much needed exhibition of the meeting between fine arts and disability.

In his recent book, Bad News Days: Art, Criticism, Emergency, renowned art critic Hal Foster describes four paradigms that weave throughout contemporary art in the 1980’s and 90’s. Christopher Knowles’s work easily fuses three of these four: the abject, archival, and mimetic.

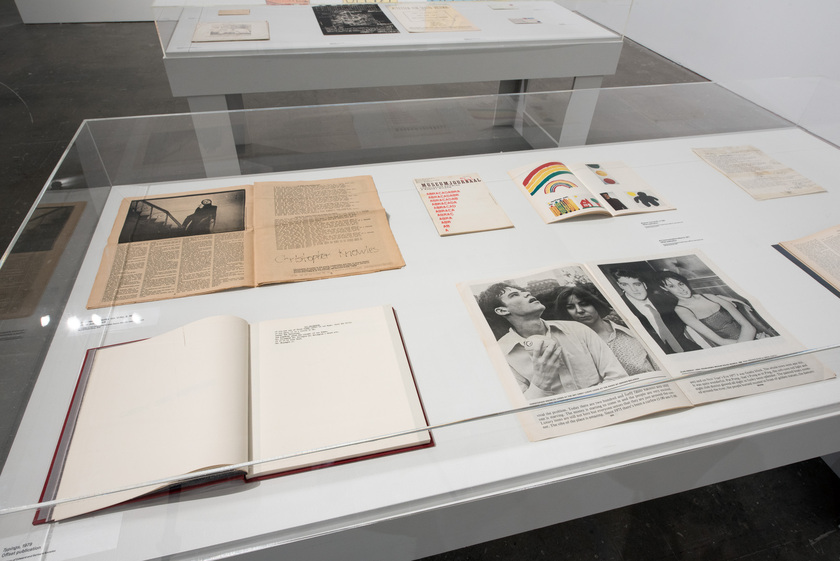

As you walk into the ICA’s expansive and ever-changing Eleanor Biddle Lloyd Gallery, the first works seen—and arguably Knowles’s most famous—are his typings. Somewhere between poetry and painting, Knowles meticulously types out a series of words or more often the letter ‘c’ in either red or black, sometimes more colors, into lists or, as seen above, a representation of a Casio watch. What separates his typings from concrete poetry and minimalism and places him distinctly between the two is the content. Numerous lists appear which aim to describe who was located at a certain place or comparing similar-yet-different words or phrases: “she’s angry,” “I got so angry,” “she’s upset,” “I got so upset.” The difference in repetition reveals that these typings are less poetic representations or mere pictorial word play, but information digestion made visual.

Foster notes in his book that “archival artists are drawn to historical information that is lost or suppressed, and they seek to make it physically present once more.” In many ways Knowles’s work is a self-addressed archive, capturing moments where the artist (and I’m conjecturing here) desired to objectively study bits of language or information and so he captured it into lists and typed pages. He forces what appear to be ephemeral moments—who was at this reading, an advertisement from the radio, learning the difference between “breeze” and “sneeze”—into physical, tangible art objects.

Near his typings are displayed a series of his photographs, shown en masse here for the first time: all capture domestic or landscape scenes that are entirely devoid of people. Each image becomes an archival object of that very moment, of the rational and objective space, that, because of the photographs remains, accessible. His visual paintings also capture discreet moments: street scenes or a group of people displaying a variety of emotions. One gets the sense that, like his typings, this archive is intended to stop the flow of unending life information in order to, I would argue, more attentively digest it. In his street paintings, each element of the scene’s form never quite fully touches each other. Each discreet element becomes a color block, another piece of the informational gestalt-puzzle, which can be understood separately or connected together to create a larger picture.

Other moments of Knowles’s personal archive pop up: in an alcove of the gallery, there is an installation set up for a performance of The Sundance Kid is Beautiful on November 11 and 12th. In the easily three stories high recess set aside for the performance, Knowles has covered the entire space with full-print newspapers, scattered around the floor are folding chairs and papier-mâché cones, as well as tens of alarm clocks noted to be from the artist’s personal collection. The clocks, like much of his poetry and typings, tick away in a repetitive chorus that occasional erupts with a burst of difference: the sounding of an alarm bell. The scene sounds and reads like a fugue of time passing.

This installation, as well as a number of his other works, also touches on another of Foster’s paradigms: the mimetic. In one painting Knowles has recreated the Homeland Security Advisory System, which placed the national security risk somewhere in a color chart between severe (red) and low (blue). This recreation he does three times in expanding sizes.

Foster writes, regarding the contemporary avant-garde:

Not heroic, this avant-garde will not pretend that it can break absolutely with the old order or found a new one; rather, it will seek to trace fractures that already exist within the given order, to pressure them further, to activate them somehow. Neither avant nor rear, this garde will assume a position of immanent critique, and often it will adopt a posture of mimetic exacerbation in doing so. If any avant-garde is relevant to our time, it is this one.

If Knowles work fits Foster’s bill for the contemporary avant-garde, which I would argue it does, then we can read his work through this process of mimetic exacerbation, one that recreates the world in order to push its fissures to the limit.

In his information-digestion-made-visible, the viewer is quick to read a sense of kitsch out of Knowles work. The repetition of the Homeland Security Advisory System’s reveals its brightly colored cartoonishness, which becomes highlighted with each larger painting. His representations lay at a stark contrast to the chart’s purpose as a gauge for terror and danger. One could read into this a slew of political commentaries on the Bush administration and the War in Iraq, or perhaps into the futility of reducing the complexity of international affairs down to a color, but this is up to the viewer to decide.

His mimesis isn’t only object-oriented. Sprinkled throughout the Biddle gallery are works that touch on wordplay as well. One painting shows a caricature of a bomb upon which is written the words “TIME BOMB.” Here Knowles reveals the backwards logic of an idiom. Another painting has the words “Barack Obama on top of” with a line and then “Mitt Romney” down below. In his quest to process the literal reality of, well, reality, Knowles’s view of our culture’s fractures highlights our peculiar disconnects as much as he delights in probing our absurdities.

And I would be remiss to point out that the mass of Knowles’s work is, conceptually, mimetic. Many of typings recreate the experiences around him. One of his earliest works, Emily Likes The TV, which first caught the attention of Robert Wilson, had Knowles repeating this phrase over and over again each time emphasizing a different word. Similarly, from the libretto of Einstein, one can piece out snippets from radio commercials, most famously for Crazy Eddie’s, an electronics retailer in the tri-state area known for his outlandish commercials. Or, as seen in this exhibition, his typing Untitled (Ronald Reagan’s Budget) that is quite actually just that: Ronald Reagan’s proposed 1983 budget.

While one can understand Knowles own impetus for his work through an archival scope, and formally his reliance on mimesis is clear, the viewer’s reception is colored by our inference of his intellectual disabilities and, as a result, this fulfills a third paradigm set forth by Foster: abjection. Popularly coined by Julia Kristeva in her search for the line between subject and object, she posits the abject as something which exists in-between, those things that tear at social reason, that lay outside the symbolic order. For Kristeva, it’s the body’s rejections: piss, shit, blood, vomit, and the ultimate I-no-longer-I: the corpse. These are the things that remind us that will not always be, that our bodies are objects that will one day die.

Knowles work doesn’t not wallow in the bodily abject, there is no piss or shit here. But I believe his work, though playful and oftentimes bright, does carry a certain repulsion to it. Elms and Als write in their gallery guide:

Knowles was diagnosed early on as autistic. As a child he learned to speak through repeating and memory, such as recalling what the Beatles intoned, what songs were popular, and how his little sister, Emily, felt when she watched TV. Recording his responses, Knowles’s early work was a startling combination of words and performance—the voice looking for an “I.” Knowles measures himself as he becomes an “I” in his sharing and documenting of the regulating routines of life—work, eat, watch, play, listen, sleep.

In his search for “I,” Knowles reveals to the viewer what makes his work endlessly mesmerizing and different: his disability. There is no way to work around such an inherent aspect to the work and thought process of an artist. At one point, Knowles’s idiosyncratic processes of information digestion are fascinating and yet, for anyone who has sat through the over four hour long performance of Einstein at the Beach can attest to, it becomes repetitive and off-putting quickly. It is clear to say that Knowles has not won over every critic (i.e. John Simon’s now-famed takedown of both Knowles and Robert Wilson).

Robert Wilson, when interviewed regarding Einstein on the Beach, said that he asked Knowles, “Who is Eintstein?” To which Knowles, at this time an adolescent, responded, “I don’t know.” Wilson posed Knowles the same question over and over again to the same response. After a few minutes of this, Knowles finally responded with, “Well, let me think about it.” He then came back to Wilson a few days later with his typed thoughts as to the nature of Einstein, which is where the quotation at the top of this review comes from. To Knowles, Einstein could be “a balloon. It could be Franky. It could be very fresh and clean.”

Knowles’s autism is what separates his “I” from, in this case, my own “I.” We simply register the world differently. His world, to me, seems systematic and computed and almost cyborgian in its effort to organize and understand complexity. I, on the other hand, can (and must) gloss over life’s complexity. Within this disconnect we differ at a Freudian level and in our difference there lies a sense of abjection.

This is not say that a viewer should or could think of Knowles as lesser than, which is a shamefully real reaction to individuals with disabilities, but the unqualified difference is real and there. Watching Knowles play two simultaneous games of Simon Says or repeating the spelling of the full name of the folk singer Donovan into a tape recorder separates his “I” from my own: this is not how I think or express myself. His mastery of repetition, which he performs as both a poet and musician (which made his libretto the perfect match for the repetitive music of Philip Glass), also places him, in the viewer’s reception, somewhere between human and automaton; he blurs the line between subject and object.

Without incorporating Knowles’s personhood, which is beyond question and quite inherent to his work, the exhibition could quickly have become a mere disability-on-display, which is both damaging and shameful. However, Elms and Als so clearly chose works to highlight Knowles’s whimsical and humorous personality and illustrated his range of emotions (a plate reveals the words: “JOHN ASHBERRY GOOD JOHN SIMON BAD”). The exhibition feels not only like a responsibly curated but also a much-needed focus on an artist with a disability. And, if fulfilling three of Hal Foster’s four paradigms of contemporary art is the criterion for a far-reaching and complex artist of the avant-garde, then I would say Knowles fits the bill.

Christopher Knowles: In A Word will be on display at the Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania until December 27, 2015. Co-curators Anthony Elms and Hilton Als will publicly discuss the work of Christopher Knowles on October 7, while Robert Wilson will present the Lauder Lecture on Contemporary Art on October 12. Knowles will perform The Sundance Kid is Beautiful in the gallery on November 11 and 12.