The Hairy Who: Reframing Rebellion // Profile of the Artists

by Kate Pollasch

My thoughts begin in the bathroom. Not in the bathrooms that house stalls with their juvenile jokes, love notes, and graffiti scrawled on their walls, but in Roger Brown’s second floor bathroom, now preserved as a house museum, at the Roger Brown Study Collection. Walk up the winding stairs to this Chicago space, and a curator may have you open the medicine cabinet door, where you will reveal shelves cohesively covered with whimsical doodles, a displaced tooth, a bottle of wood glue, and other accessories. It is within this micro-space of carefully curated corners that I remember locating the macro-ethos of The Hairy Who and the Chicago Imagists (collectively referred to as the Imagists) as a whole. For this group, every crevice of life, every daily moment and interaction, was an opportunity for subversion, artistic intervention, and nonconformity.

Recently, there has been a pronounced resurgence of interest into Imagist history. Beyond crediting this focus to mere hindsight, or considering it as evidence of revisionist work, there is something propelling their legacy into the twenty-first century.

What is it about the Imagists’ rebellious example that is so relevant today?

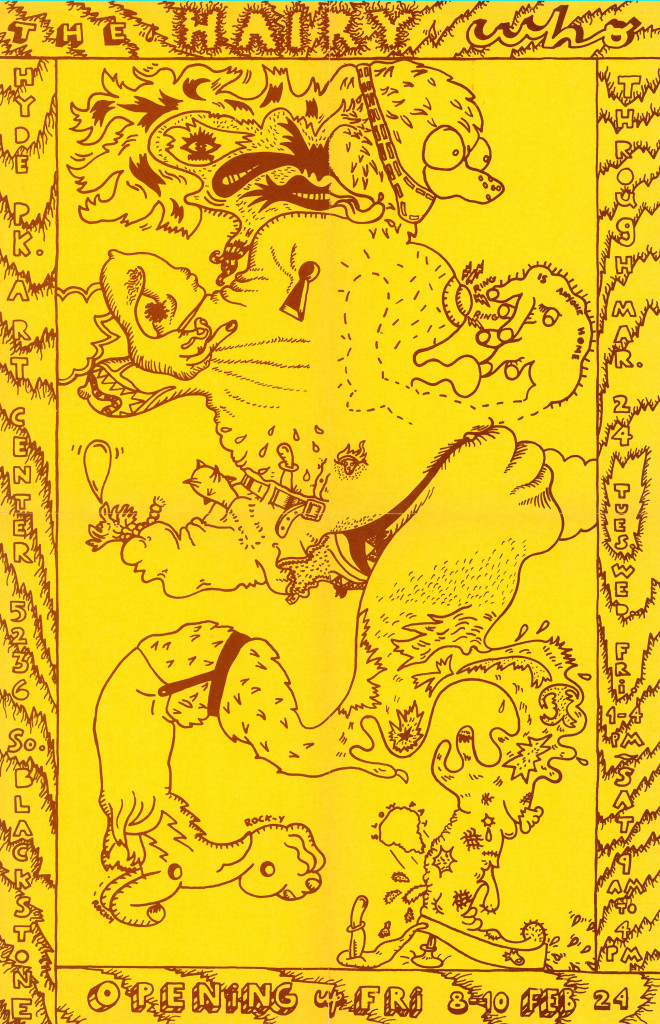

The Imagists’ story starts roughly in the 1960s and 1970s—where a constellation of Chicago-based artists, including Roger Brown, Philip Hanson, Gladys Nilsson, Jim Nutt, Christina Ramberg, Suellen Rocca, Barbara Rossi, and Karl Wirsum, among others, worked and exhibited together in a collaborative, collegial, atmosphere. In the early 1960s, the art scene in Chicago offered little opportunity for young artists, and many of the Imagists’ politically brassy, “low-brow,” comedic, and sexually charged work did not align with the New York commercial art atmosphere. In decidedly not waiting for New York to come calling, and resisting the search for approval from an even more distant art world overseas, the Imagists instead produced their own alternative group exhibitions. Their openings consisted of giving out comic-book style decals and catalogues, coating walls with brightly patterned mismatched wallpaper, or incorporating found objects into the installations. The Imagists’ exhibitions were, and still are, the antithesis of a pervasive “white cube” style. Their work was polarizing; garnering both admiration and harsh critique. Brown himself even published scathing reviews of the very critics who admonished their self-created scene.

From this early point onward, each artists’ career followed a trajectory all its own—though generally, the Imagists continued to will a place for themselves in an often oppositional atmosphere well into the later part of the following decade.

The return to a more collective model of working was not necessarily new then or now, and is rather expected at historic moments such as the turn of a century, or major shift in industry—we need only look to the Romantics, Dadaism, or the resurgence of Arts and Craft. But in the twenty-first century, the form has been co-opted by both mainstream commercial industry and non-profit or alternative art communities, allowing artists to operate in both spheres, free from old-guard rigid ideas of either “selling out,” or pledging allegiance to the “alterative.” Artists are now faced with both.

In the wake of an oversaturated art market, with its limited funding and the ever-churning art school industry, international contemporary artists are building their own opportunities outside of the mainstream art market, very similarly to the Imagists’ midcentury model. In Chicago, this self-made spirit is still evident in the structure of apartment galleries, a concerted emphasis on the interdisciplinary, and pop-up spaces. This, paired with an increase in contemporary artists who use the Imagists as a source for their work, raises questions on how and why the group’s original concepts of rebellion are being interpreted.

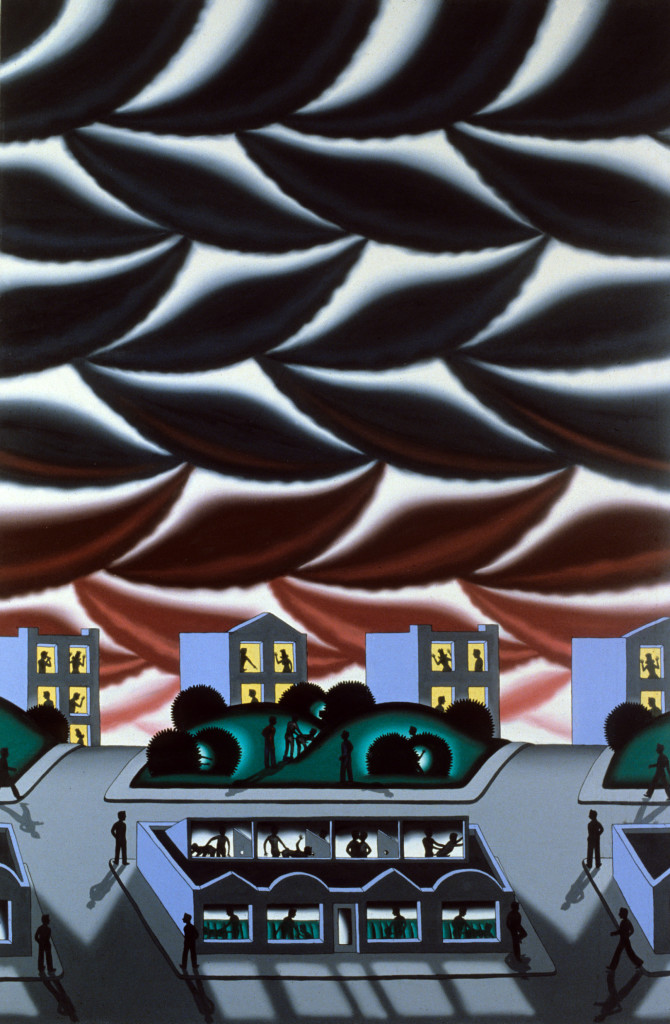

In the 1970s and 80s, Roger Brown’s paintings unhinged the walls of high-rise buildings and cut open the roofs of structures throughout the city, to illuminate figures engaged in normally unseen erotic activity. Before the International Mr. Leather competition was a well promoted Chicago event, Brown rendered the predominantly unknown and underground leather Gold Coast Bar on his canvas, elucidating a fantasy where sex and desire slipped into every room, behind every bush and tree, and on every level of Chicago’s architecture. But even with the Imagists’ subversive agency at the time, much of Brown’s erotic work was held back by his commercial gallery, and minimally addressed in art history.

However, now when the erotic is familiar, even expected in the white cube, Brown’s approach speaks more to individual intentionality than it does to pushing the limits of titillation. Chicago-based artist Edie Fake continues this trajectory—the graphic linear quality of his paintings, and the kaleidoscopic electric palette references to the group’s formal aesthetic, echoes the conceptual concerns of the Imagists’ work. Whereas Brown cut into Chicago’s landscape to visualize a dream of group sex and erotic space-making for the predominately oppressed and invisible gay community he identified with, Fake builds up traces and fantasies of buildings that speak to notions of queer and trans history, utopia, loss, and identity. Channeling the ethos of Brown and using the Imagists’ dissident approach, Fake’s work lives in less of a binary art industry than his predecessors. Fake’s generation is one that can be featured in a commercial gallery—Fake’s recent solo exhibition Grey Area at Western Exhibitions—while at the same time it can receive the Ignatz Award for Outstanding Graphic Novel, Gaylord Phoenix.

In an increasingly institutionalized scene, there are still moments within the commercial and non-profit structures built around contemporary art that allow for the same collaboration the Imagists sought out nearly sixty years ago.

While the likes of Gladys Nilsson, Karl Wirsum, or Art Green celebrated the strange and uncanny, making exquisite corpse drawings together and believing in the spiritual essence of a unique flea market object, high-market artists such as Jeff Koons’ practice presents a flip of this culture, reveling instead in the high gloss manufactured star power of consumer capitalism. Locally, the non-conformist legacy of the Imagists reverberates in smaller organizations, such as Threewalls’ publication PHONEBOOK, and Temporary Services, whose website states, “The distinction between art practice and other creative human endeavors is irrelevant to us.” But this influence is also on a larger scale, creeping into established institutions and galleries, such as Corbett vs. Dempsey, whose program champions Imagist art history. Existing as a model of Imagist ideology itself, the commercial gallery fosters musicians, self-taught artists, international film screenings, and a record shop. Concurrently, The Freedom Principle: Experiments in Art and Music 1965 to Now, on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, offers an uncanny harmony to Karl Wirsum’s fusion of jazz, blues, and painting on an expanded curatorial scale. It was in fact Wirsum’s iconic portrait of musician Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, which visualized his raw theatrical presence so perfectly, that was used on Hawkins’ 1970 album cover. This crossover of art into ephemera, home collections, and collaborative practices was recently recognized in New York at Matthew Marks, both through an exhibition and publication that features the group’s collected publications, available this month.

In the necessary plurality of today’s art world—between titles of artist, curator, designer, and collector—the current of the Imagists’ counterculture is more relevant now than ever. In willing an individualized ethos into existence amid the unique economic structure of the art world today, the Imagist-style of rebellion offers an example of the idiosyncratic, hybridized system that led to the grounds for their work then, and perhaps a generation to come.