Laura Owens: Whitney Museum of American Art

by Terry R. Myers

One of the added benefits of this well-timed mid-career survey of Laura Owens’ paintings comes from it having been organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art. Lately, we have been reminded that painting can still matter, which it always has—despite, or perhaps because of, the haters (who sometimes have been painters themselves). Agile painting weathers rather well in terms of being attacked or celebrated (which is sometimes the worst of the two reactions), including, of course, at this lightning rod of a museum that, to its credit, has stuck with the medium. With that said, I entered the fifth floor of the museum, where the majority of Owens’ output was on view, thinking about the risks that some painters are still more than willing to take— ready to go somewhere uncomfortable, if not painful—and willing to take something comforting, and make it more complicated than we ever imagined it could be. I remain convinced that a great painter is extra capable of doing this, mainly because of how paintings still get made. I was thrilled recently to read somewhere that Carolee Schneemann (a role model for Owens) was quoted stating “I don’t have a practice, I have a process.”1 The important contemporary painters of our moment still make full use of sources and methods, and are willing to put painting (and paint) through its paces, and take their lumps for doing so.

I have been fortunate to have seen a great many of Owens’ exhibitions, but after this effective survey, it is clear that she damn well knows how to make a painting. And I think she has gone about it in a beautifully Los Angeles way, meaning, for example, such things as: boundaries are pretty boring, what makes something like something else is often more interesting than what makes it different (even if you’re “faking” it), and never, ever forget that you are in a production town.

When Owens was a graduate student at CalArts, she not only survived her first “painting is over” chatter in the early 1990s (having resisted it myself, it seems super lame now), but also the January 1994 Northridge earthquake. I like to imagine that it was the literal instability of that situation that helped her wait until after the dust settled to make some bonafi de and still killer paintings: at the opening of her 1995 solo exhibition in Los Angeles I had written down “paradigm shift” in response to what I took as one powerful tremor of a debut exhibition. Now, I cannot help but think about de Kooning’s passion for what he called “trembling,” a quality he found in a broad range of art from the Egyptians to Cézanne, who, in particular, “was always trembling but very precisely.”2 Owens’ standout painting then remains so now: Untitled (1995) is, on the one hand, a depiction of a ridiculously expansive gallery—a green wave of a wall sweeps right across the right the top of the canvas, and is “hung” with a salon-style array of miniature versions of paintings: some hers, some not, some painted by her, some not. On the other hand, the formal all-overness of the painting challenges all of that depiction by deploying a material and painterly complexity that she has built upon ever since, even if most of its surface area is raw canvas.

The exhibition reinforces Owens’ ambitiousness over and over. Somehow, it is a big show, but does not feel packed. Part of the reason for this is the artist’s commitment to representing key paintings in new versions of the specific situations she encountered or created in the original presentation of the work. Her skills as an installation artist are significant. Two different Untitled paintings from 1999 are in similar situations they found themselves in nearly twenty years ago—and, as if for added structural and inclusive emphasis, both are diptychs. The first is the so-called Monkey painting, made originally to work and play with the wall of her London gallery, and the troublesome column in the middle of the room, and the second is what I have called the Numbers painting, produced for the 1999 Carnegie International, where it was also installed on opposite walls so that you would (as I wrote at the time) “have no choice but to come between them.” Hung in a corridor within the Whitney galleries, the numerals on one canvas are still able to look as if they have been projected in reverse on the other. Reading as connect-the-dots numerals, the paintings make the game appear even more mutual.

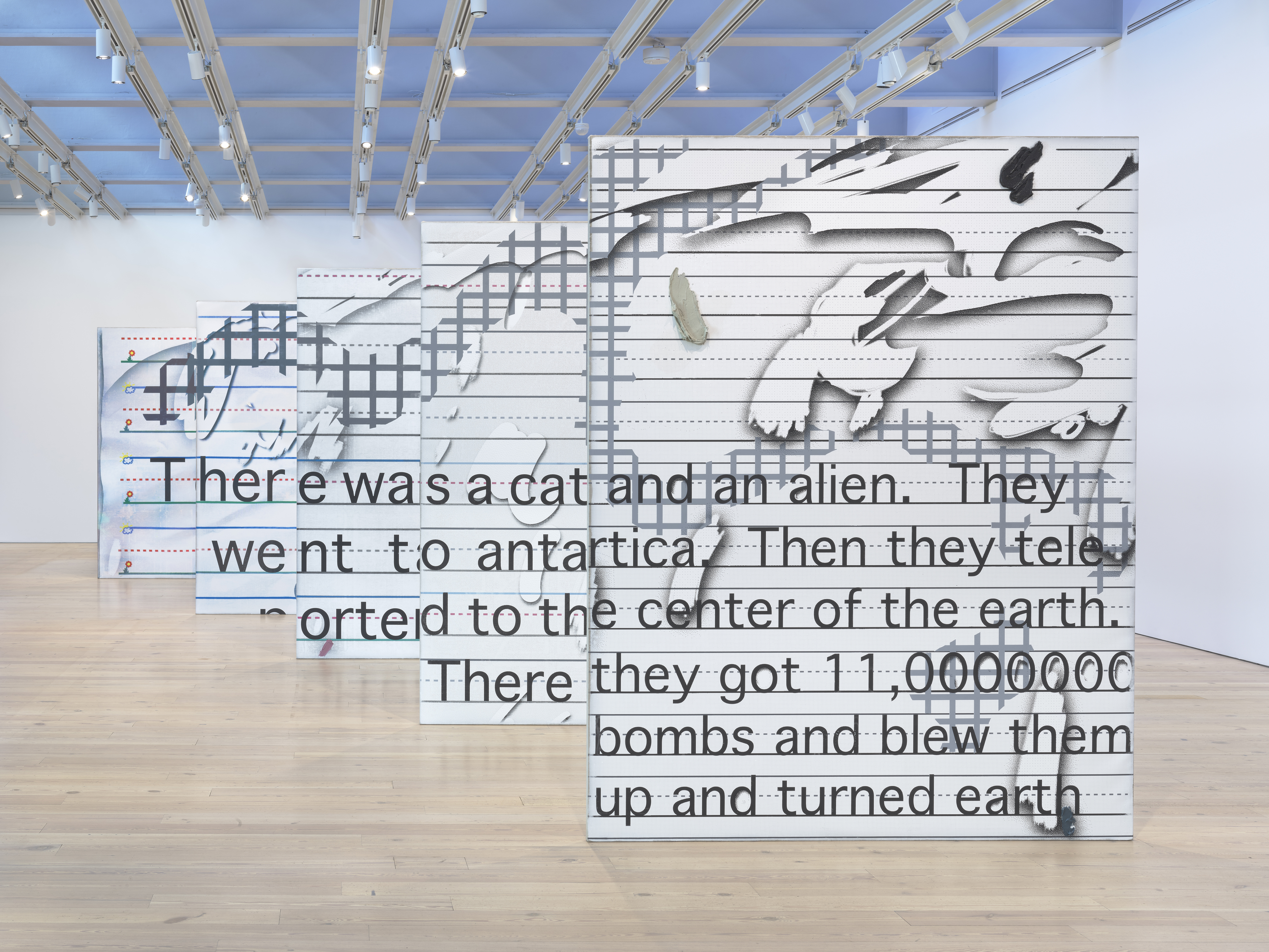

This involvement of the viewer is the big take away from this boisterous exhibition by a tough but generous painter: while perhaps each of us gets in the way of Owens’ paintings, she would not have it any other way. We are asked, for example, to locate a particular vantage point to read the words in the series of large-scale freestanding panels of Untitled (2015), impeccably installed on the eighth floor to give us plenty of room to perform some focused flanerie around them. Similarly, viewers are invited to interact via text message with several Untitled works from 2016 made of wallpaper, which were cut from the walls of their original presentation in San Francisco—their embedded speakers and prerecorded responses still operational. In the exhaustively playful catalogue for this survey, David Berezin lets us in on a secret: “[I]f you texted the question ‘Where are the paintings?’ all eight of the speakers would activate at different intervals and say the word ‘here.’ So it was like, ‘Here,’ ‘Here,’ ‘Here,’ ‘Here,’ bouncing around the room.”3

Yes, paintings can come to us—but we must go to them.

Laura Owens at the Whitney Museum of American Art ran from November 10, 2017–February 26, 2018.

- Hyperallergic, “Carolee Schneemann on Five Decades of Meat, Harnesses, and Innovation.” Online, October 2017.

- Willem de Kooning, “A Desperate View,” in The Collected Writings of Willem de Kooning (Madras and New York: Hanuman Books, 1988), p. 11.

- David Berezin, “Ten Paintings,” in Owens, Laura (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2017), p. 594.