Lola Álvarez Bravo: Picturing Mexico

by Annette LePique

Lola Álvarez Bravo: Picturing Mexico, the newest exhibition at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation in Saint Louis, is an insightful delve into the personal and idiosyncratic archives of one of Mexico’s first female photographers. Curator Stephanie Weissberg’s intimate focus on Lola’s private, experimental work forms a focal point that both anchors and expands viewer exploration of Lola’s practice—an interlocking web formed by anti-colonialism, Surrealism, the shifting ethnographic character of an industrialized post-revolution Mexico, and the artist’s own community of fellow thinkers and makers. The pieces that compose Picturing Mexico span from the 1930s to 1970s and feature a diverse array of subjects, but all share a sense of expectation: an anticipatory desire to experience and discover the image. These are photographs that require a “certain concentration”1 in order to be read—a quality which Lola herself characterized as “a sense of mystery, of surprise,”2 the bruising jolt of Barthes’ punctum. Centering Picturing Mexico on Lola’s profoundly personal works, combining a radical humanism with her experiments with the uncanny, provides a nuanced view of an oft overlooked female artist’s life and work.

Born Dolores Martinez de Anda in Jalisco, Mexico, Lola was introduced to photography in the early ‘20s by her long-time friend, and soon to be husband, photographer Manuel Alvarez Bravo. Both Manuel and Lola grew up during the Mexican Revolution and witnessed their country experience tectonic shifts in industry and culture. The couple married during the mid-20s, had one child, and divorced approximately a decade later. Lola’s divorce functioned as a pivotal moment in her life as it provided sudden independence and urgent economic need. Such need translated to Lola’s pursuit of photojournalism, commercial photography, and professional portraiture as means to support herself and her child.

Though marital relationships are fraught ground in any discussion of gender, artists, and making, this truism is pertinent to discussion of Lola’s early work. Lola’s early photographic experiments were routinely overlooked in favor of Manuel’s own artistic renown; a phenomenon that unfortunately came to define Lola’s art for the majority of her life. Mention of the long shadow Manuel cast over much of Lola’s life and work is not an attempt to reinforce such a relation but rather the hope to recognize, define, and deconstruct this power differential. Such deconstruction allows for a better understanding of the expanse of Lola’s work and unique contributions to the photographic field.

Post-divorce, during the mid-30s, Lola became chief photographer for El Maestro Rural, a monthly magazine published by the Ministry of Public Education for elementary school teachers,3 one of her first governmental photography assignments. As Lola’s position required a great deal of travel through rural and urban areas, she encountered hostility from men in her profession. Lola recalled such challenges succinctly: “I was the only woman fooling around with a camera in the streets, all the reporters laughed at me. . . so I became a fighter.”4

Though motivated by economic need, Lola’s determination to flourish within a male-dominated field stemmed from her own deep belief that her work was valuable as her photos showed “a Mexico that no longer exists.”5 Lola’s commitment to honoring the shifting cultural identities that composed a post-revolution, wartime Mexico stemmed from an anti-colonial influenced naturalism. Lola’s works presenting scenes from indigenous communities and the urban poor are unlike most early ethnographic photos of the time: images featuring posed subjects and artificially constructed surroundings. In contrast, Lola’s photographs are intimate gestures infused by the vibrant humanity of all her subjects.

One of Lola’s most famous photographs Entierro en Yalalag (Burial in Yalalag) (1946) constructs such sight for the viewer through the use of light and shadow. A group of indigenous Zapotec peoples are performing a burial ceremony in traditional, long white huipiles that shine bright against the desert landscape. Mystery and pain intertwined to capture an image marked by honesty.

This unremitting honesty with the camera lens constituted an act that, at the time, was deeply transgressive as Mexico was (and, like the United States, remains) a country grappling with its intertwined legacies of colonial wealth, inequality, and racism. When Lola was interviewed and asked about the challenge of exploring potentially painful subjects she stated that no matter what the image, with her camera, the subject will be seen and admired “por el camino de la luz”—through the path of light.6 The spiritual connotations of Lola’s comment notwithstanding, what stands out about her use of light is the simple notion that with light one is seen; the body and its pain and its mystery, is seen.

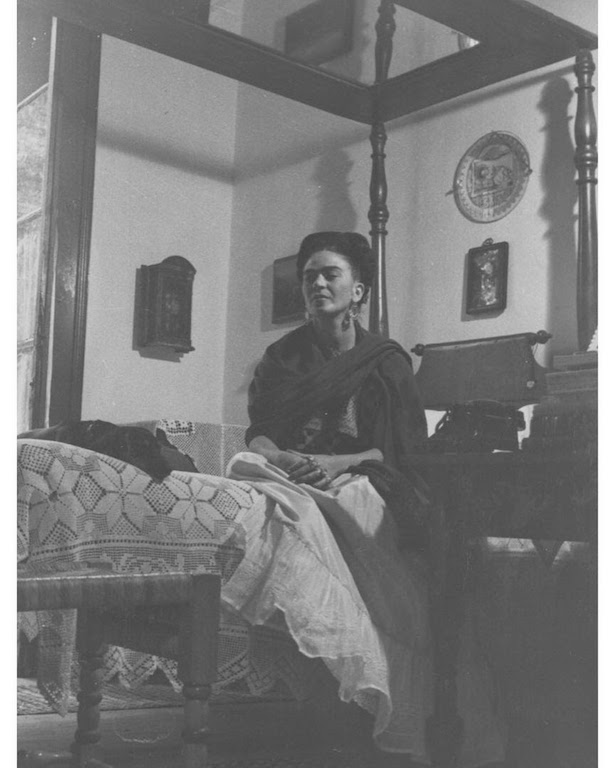

These acts of care and witness translate to Lola’s portraits of her friends. Wide-ranging and eclectic, Lola’s social circle included both Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, with Lola opening the art gallery that presented Kahlo’s first solo exhibition in Mexico.7 Frida Kahlo (on her bed) (1940s) shows Kahlo sitting upright on her bed, intimate and vulnerable, a reminder of the chronic illness and pain featured in much of her own work. However, there is a strength present in that this is a portrait of the artist’s friend, another woman comfortably sitting and slightly smiling in her space.

Yet, Lola experimented with portraits by transporting her friends and subjects through the boundaries of daily life. Lola removed her subjects’ bodies from their usual environments, uncannily reshaping the ethnographic boundaries she rejected in other work as she utilized these incongruous moments between the subject and space to create new, dreamlike associations. In Lola’s portrait of architect Ruth Rivera Marin, viewers can see Marin’s dark hair stain the foreground while the expanse of the log masks the full nature of her partially submerged surroundings. With Marin’s eyes closed, face to the light, she is reminiscent of an otherworldly Ophelia burst forth from the shallows.

The aesthetic and political threads that link Lola’s work allow for viewers to begin conversation on the pleasures and needs that motivated her drive to create. Beyond belief in any ideology or aesthetic leanings, there was an ever-present belief in herself: a woman who both recognized her vision was both bound by her time but boundless with light.

Lola Álvarez Bravo: Picturing Mexico runs at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation until February 16, 2019.

- James Oles, “Like Cut Glass An Approach to the Photography of Lola Alvarez Bravo”, Lola Alvarez Bravo in Her Own Light, trans. James Oles, University of Arizona Center for Creative Photography, 1994 (23).

- Elizabeth Ferrer, “The Third Eye”, Lola Alvarez Bravo, Aperture Center for Creative Photography Foundation: NYC, 2006 (46).

- Oles, “Like Cut Glass An Approach to the Photography of Lola Alvarez Bravo”, Lola Alvarez Bravo in Her Own Light, 19.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Oles, “Like Cut Glass An Approach to the Photography of Lola Alvarez Bravo”, Lola Alvarez Bravo in Her Own Light, 21.