For Love and Money: Summer of Love—Art Fashion, and Rock and Roll

by Stephen F. Eisenman

The City by the Bay is celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of the Summer of Love, but there is a wintery vibe here. Eight thousand people are living on the streets, and sky-high rents (an average $4,500 for a two-bedroom apartment), have turned students and artists into threatened species. Federal targeting of the LGBTQ community and immigrants, in a city with lots of both, creates a feeling of siege. Weed is legal, but cannot be smoked on the street, so tokers hide in alleys and in the corners of parks, creating a menacing atmosphere beneath sweet, smoky clouds.

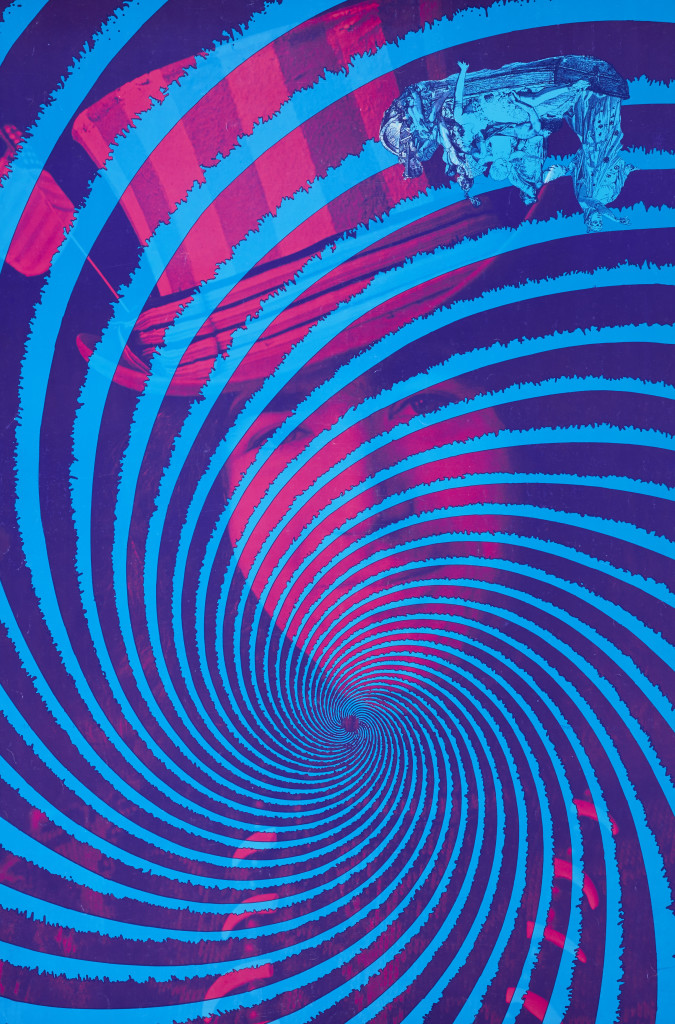

offset lithograph poster. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Walter and

Josephine Landor, 2001.97.29A. © Walter Medeiros / Sätty Estate. Image Courtesy of

the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

And then there is the marketing: there are Summer of Love trading cards promoted on billboards and kiosks; advertisement for hotels and attractions that deploy a Magical Mystery Tour typeface; and lectures, exhibitions, and scholarly symposia exploring hippies, LSD, psychedelic posters, and the counterculture. When an avant-garde has graduated to the seminar room, you know it is truly dead.

This leads us to the exhibition at the de Young Museum, Summer of Love – Art, Fashion and Rock and Roll. It is the third exhibition in recent years devoted to a similar topic—the first, which started its tour in 2015 at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, was called Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia, and contained art that few people have ever seen, as well as design, architectural models, music, film, dance, and psychedelic rock posters. The second was Say You Want a Revolution: Records and Rebels, 1966-1970 at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London in Summer 2016, and was bigger, more distracted, and less successful, as it tried to be groovy. The darkened galleries, thumping music, costumes, liquid lights, and once again posters, created a disco atmosphere that was untrue to many of the materials on display. Given its title, what was worse was that it paid insufficient attention to the politics and economics of the music business, which while difficult to exhibit in a museum context, could have been done with the right graphics, didactics, and installation. The exhibition at the de Young museum has a different focus than the previous two: more fashion, less music, and less art. In fact, except for the posters and photographs, which are mostly documentary, there is no art in the exhibition at all, save for two lonely but terrific paste-ups by Jess (Jess was a crucial figure among Bay Area artist’s for his campy Surrealism and openly queer lifestyle). There are however numerous posters by the five greats: Alton Kelly, Stanley Mouse, Victor Moscoso, Rick Griffin, and Wes Wilson, though the many works are so scattered throughout the exhibition that they resemble wallpaper, which falsifies their aesthetic and purpose. While the originals appeared side by side, and installed floor to ceiling in the places they were originally sold, such the Print Mint on Haight Street and Freidman Enterprises on Grant Avenue, they were intended for individual contemplation on the streets or in rooms—preferably while stoned.

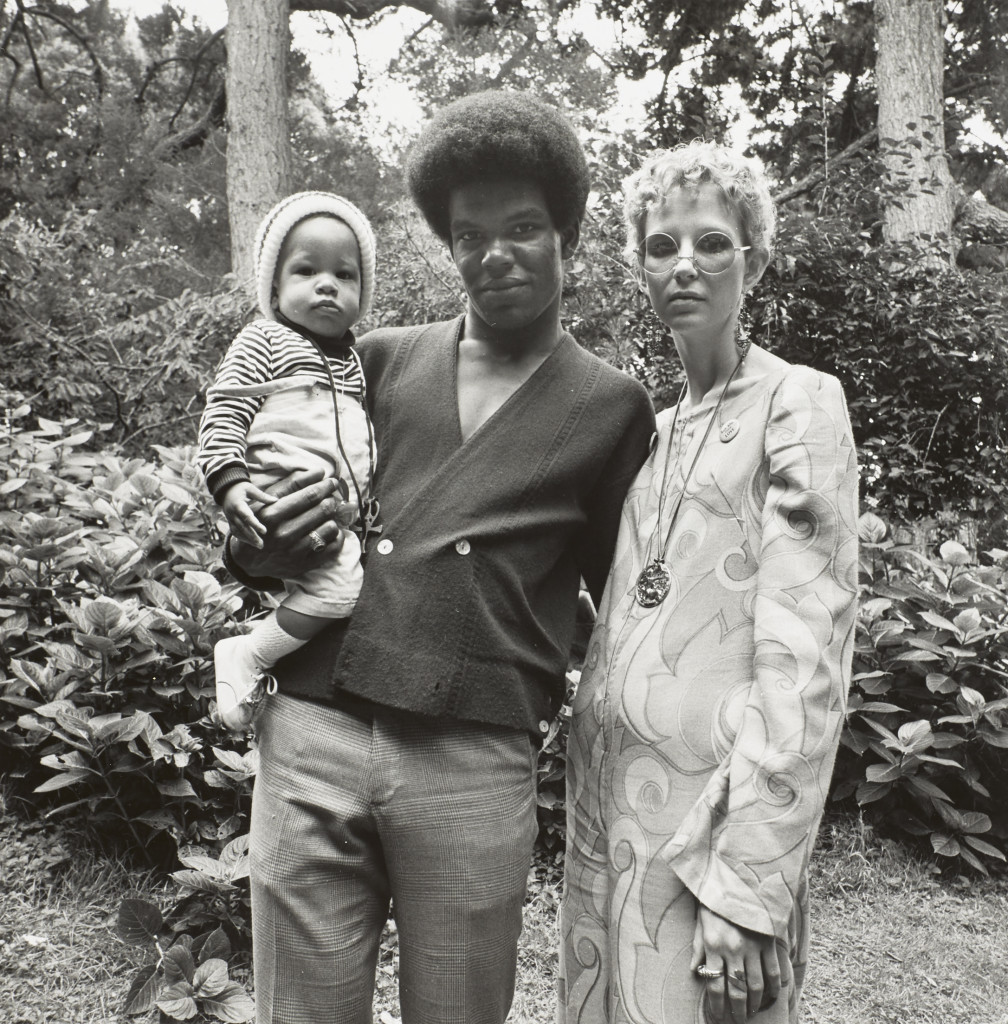

Gelatin silver print. Lumière Gallery, Atlanta, and Robert A. Yellowlees. Courtesy

Special Collections, University Library, University of California Santa Cruz. Pirkle Jones

and Ruth-Marion Baruch Photographs. Image Courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of

San Francisco.

The posters’ strange typography and layout (letters were often sculpted from negative space), combined with their optic vibration, rendered many unreadable except after long examination. The idea was to slowly feed into your head names like Quicksilver Messenger Service, The Doors, The Grateful Dead, The Steve Miller Blues Band, Big Brother and the Holding Company, Filmore West, and the Avalon Ballroom. Moscoso’s poster, Neptune’s Notion (1967), designed for Moby Grape at the Avalon, combines unlikely source material—an Ingres’ painting of Jupiter and Thetis (1811) and found images of stylized fish—into a bizarre and unforgettable ensemble. (Either Moscoso got his mythology wrong—Neptune and Jupiter have nothing to do with one another—or he invoked the sea gods in reference to Melville’s white whale, as the first name of the rock group was Moby.) Moscoso’s training with color theorist Joseph Albers at Yale is apparent here: the complementary blue and orange establish an electric middle plane while the hot magenta of Thetis and Jupiter advances toward the viewer.

However, the real core of Summer of Love is the clothes: denim, tie-dyed, woven, crocheted, leather, vintage, tight, loose, mini, floor length, patched and fringed. Their histories tell an important story of insurgency and appropriation. Take the case of Luna Moth Robbins, (born Jodi Paladini), who from 1966–68 was a member of The Diggers, a small but influential San Francisco anarchist and performance group that among other things, established free food and clothing stores. In 1967, Robbins tie-dyed white shirts that had been donated to the store, in order to promptly give them away. Afterwards, she taught her skills to Ann Thomas (aka “Tie-dye Annie”) who started a business, selling her products to Cass Elliot, Janis Joplin, and John Sebastien, among others. The trajectory traces the pathway of avant-garde into commodity culture.

Gallery, Atlanta, and Robert A. Yellowlees. Image Courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of

San Francisco

The circuit needs to be examined just a bit more to better understand what happened with fashion during the Summer of Love.

In San Francisco, disaffected young people decided to signal their alienation and assert their autonomy—as others had before them—through clothes. In this case, they rejected the tailored polyester and rayon of department stores for cast-offs from Goodwill and the Salvation Army. They particularly liked clothes that marked a distinct time and place, for example California and the American West. In some cases, they repurposed used garments to make them more colorful, expressive, or idiosyncratic. Quickly, a few entrepreneurs recognized an opportunity. They opened resale shops to cater to this market, and then in succession, small workshops to make ready-to-wear products, and larger ones to produce both off-the-shelf and made-to-measure versions for the likes of Jimi Hendrix, Sly Stone, Grace Slick, Joplin, Bob Dylan and the rest. Finally, national manufactures followed the trend. The Peace Dress (covered with peace signs), made by Martha Fox for the Alvin Duskin label, appeared in 1967, and by 1970, thousands had been sold in multiple color-ways. The entire circuit, from thrift store fashion to mass manufacture and national distribution, occurred within a single year.

print. Courtesy of Joseph Bellows Gallery. Image Courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of

San Francisco

What was true for fashion, was also true for popular music, posters, light shows, and the rest. Small communities of disaffected or dissident young people explored previously unrecognized or undeveloped expressive forms and spaces, thereby identifying for advertisers and manufacturers potential new arenas for investment and exploitation. The exhibition The Summer of Love mostly occludes this process by dispensing with chronology, ignoring the interplay of industry and subculture, and instead regularly invoking the terms “hippie” and “counterculture.” The former has a long and complex history, but only came into general use in 1967 after San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen (who earlier coined “beatnik”) used it to describe the kids who had recently moved to North Beach and then the Haight. The term “counterculture” is equally wooly. For the social scientist Theodore Roszak, who coined it in 1969, the term was a portmanteau that included a wide diversity of individuals and groups opposed to “technocratic society.” There was never a counterculture that acted in a unique manner, had uniform beliefs, or a clear program of action. So then who was it that descended upon San Francisco in 1967 during the Summer of Love and what did they want?

First of all, the influx of young people was already underway by the summer of 1966. Second, the love was vitiated by hunger, rough sleeping, sexually transmitted diseases (no HIV yet, fortunately), rape, arrests for drug possession, and lots of bad acid trips. And third, the youth rebellion was short lived. Most of the kids who attended the Human Be-In at the Polo Grounds in January of 1967, or who came to the Haight that Summer, went back to school or moved back home by the Fall. Nevertheless, something highly significant was taking place that year in the Bay Area that had little to do the influx of hippies: a proxy war over class, race and politics in the form of a contest over culture. The Diggers in Haight Ashbury, with their project of giving everything away (they even offered “surplus energy”), challenged the authority of consumer culture and the commodity circuit described above. The Black Panthers (strongest in Oakland) fostered black empowerment and self-protection. Like the Diggers, they opened soup kitchens and clinics, but also promoted the open carrying of pistols and long guns. Thus, they challenged the police monopoly of violence and conservative state legislators passed stringent gun control measures in response. The unsurprising result of Black Panther provocation, however, was FBI infiltration and massive repression.

The various US countercultures that identified with the Summer of Love, the Bay Area, and the 1960s in general, constituted a brief, and occasionally powerful challenge to prevailing political and economic structures and institution. But they operated in the face of enormously powerful assimilative forces and were met with organized state opposition. In 1968, Nixon’s election inaugurated a capitalist counter-revolution that accelerated under the regime of Ronald Reagan, (austerity, destruction of unions, imperial war, mass incarceration, retrenchment of the welfare state) that continues today. But the underlying energy and desire of the various sub and countercultures of the Summer of Love (and the like), survived the repression and has resurfaced in recent years in many forms—for example in the Occupy movement, the Sanders campaign, the resistance to Trump, and in the UK, the rise of Jeremy Corbyn’s Momentum group.

That is how radical change may happen, through the work of memory and the consolidation of forces—what in 1967 was called “a gathering of the tribes.” The exhibitions in San Francisco, and the two others that came before, only hint at the great cultural and political stakes at play during the period, yet remain valuable reminders of battles fought and lost, and as anticipations of other, greater struggles still to come.

The Summer of Love Experience: Art, Fashion, and Rock & Roll was on view at the de Young Museum from April 8 – August 20, 2017.