Maria Lassnig: New York Films 1970-1980 // MoMA PS1

by Mary L. Coyne

While spring in New York has had its share of major exhibitions by female artists—Carolee Schneemann, Adrian Piper, the group exhibition Radical Women (organized by the Hammer and touring to the Brooklyn Museum), and an outdoor rooftop installation at the Metropolitan Museum of Art by Huma Bhabha—one of the most remarkably historically important presentations of scholarship was also the most subtle. An almost unseen cinematic presentation in the basement of PS1. Largely forgotten, in terms of Maria Lassnig’s practice (an exhibition at Petzel Gallery in 2011 showcased ten films), many of the artist’s twelve brief Super 8 and 16mm films are being shown for the first time, restored for the purposes of Maria Lassnig: New York Films 1970–1980.

The MoMA presentation subtly underscores the value to be found in taking a wider look at an established artist’s body of work—a practice that all too often occurs only after their death. These films were largely never finished, nor shown in the artist’s lifetime, which perhaps accounts for their frankness, a type of elucidate meditation on the artistic process, life in the studio, and the psychologies, lives, and bodies of Lassnig’s friends and colleagues. As such, the films of this period become essential to understanding the shift within Lassnig’s practice, which occurred around 1970 following the artist’s move to New York from Vienna in 1968, to be “in the country of strong women.”1 Shifting her focus from the personal to that of the body and its relations, her reaction to the sensory overload of Manhattan was not so much an abandonment of an earlier practice of ‘body sensation’ drawings and the subsequent ‘body awareness’ paintings, but rather a redefinition of a transposed body within a cultural and civic environment.2

The exhibition’s contribution—although not explicitly stated by curator Jocelyn Miller—is a permission to view Lassnig’s work of this period within the context of other largely time-based work from Lower Manhattan during the same period, especially those of Lassnig’s peers Carolee Schneemann and Joan Jonas. In 1994, Lassnig wrote, “…Nothing has altered the fact that in painting and drawings I proceed from the same reality; the physical event of bodily experience.”3 This calls for a second look at Lassnig’s ‘body awareness painting’ that expands from their acute yet active sensual brushstrokes and contours that convey both the sitter’s and painter’s liveness, but also shows a fundamental concern with the body and its movement within a spatial environment.

By exploring Lassnig’s study of space, the exhibition foregrounds the artist’s work into a formerly parallel, yet until now separate, discourse—within a community of artists, largely settled in and near Lower Manhattan, who developed a film-centric approach to feminist artistic practice. These artists (including Jonas, Schneemann, Yvonne Rainer, and Babette Mangolte, among others) and the persistence of the performative lens of which this latter group is consistently a part of, however shortsightedly, typically exist within an orbit independent of a study of Lassnig’s practice of the same time and place. The filmic portraits of Lassnig’s Soul Sisters on view in the exhibition, including one of artist and weaver Hildegard Abasalon, are remarkable in comparison to Lassnig’s paintings from the same period, but reveal in their intimate details and painterly compositions the same psychological interrogation into her subject’s being while situating the women’s bodies, gestures, and actions within a place.

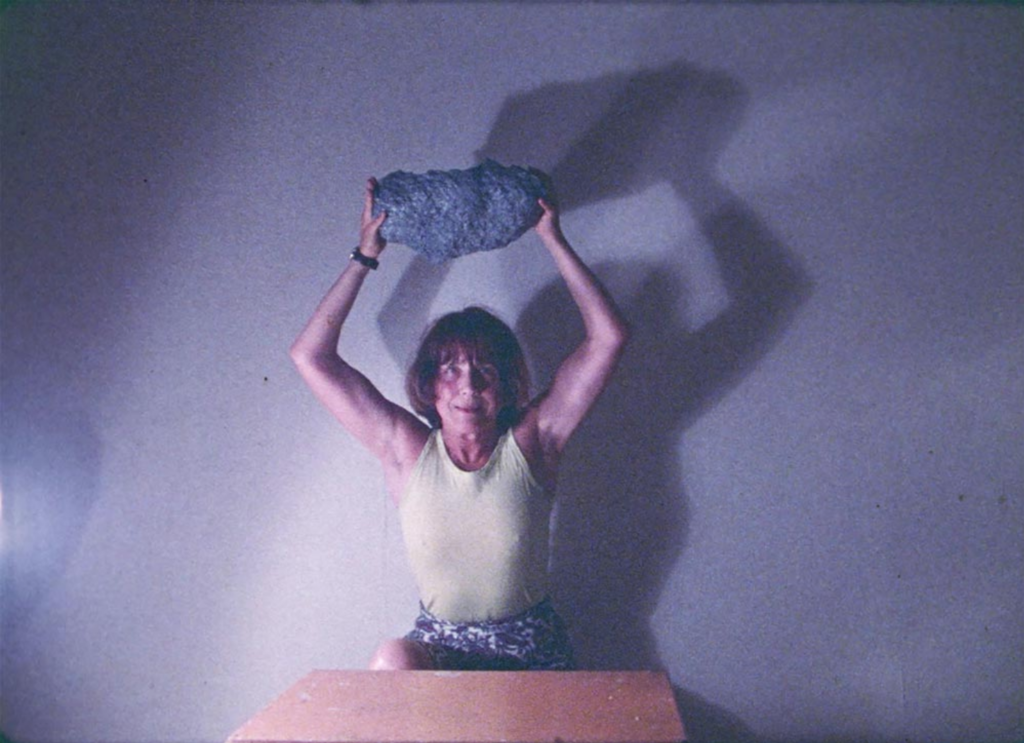

This filmic study of place has art historical parallels with conceptual practice, as in Michael Snow’s portrait of his studio from 1967, and Romanian artist Geta Brătescu’s series of photographs and watercolors (1970–1979), which take the quiet, solitude, and romance of the artist’s long-sought-for studio as their subject. Lassnig’s Stone Lifting: A Self Portrait in Progress (1971–74), is perhaps the most revealing in this approach, blending documentary film of the artist’s preparation for a 1974 solo exhibition at SoHo’s Green Mountain Gallery with candid and staged shots of Lassnig’s peers—the members feminist experimental film collective Women Artist Filmmakers Inc., of which Schneemann and Rosalind Schneider were early members. Stone Lifting (1974), one of the later works, plays at just over seven minutes, and features Lassnig broaching a simple performance for the camera, a format aptly used by Schleeman. In recurring shots edited throughout the length of the film, the artist sits frontally before the camera, repeatedly lifting, as the title suggests, a not insignificant stone above her head before letting in soundlessly drop to the studio floor. A near absurd act of struggle and tenacity—the repetition of the gesture—that cuts before the stone actually hits the floor, the film suspends any satisfactory or violent resolution. The narrative of Stone Lifting dialogues directly with the community’s occupation with female artistic labor and production. It is particularly significant as a precursor to Kantate, a 1992 filmic self-portrait, (created after the period of time this exhibition covers) in which Lassnig similarly addresses the camera and stands in the foreground of one of her own painted canvases. She recites key biographical moments of her life, as if in an attempt to resolve, through direct separation portraiture, painting, and the body.

Whether at her Avenue B studio, or summering in Carinthia, Austria, Lassnig used film as continuation of her lifelong exploration of self-portraiture—not only through dozens of paintings, but through still photography as well. Kopf (c. 1976), a short film made in Carinthia, uses stop motion animation, a skill Lassnig was learning at the School of the Visual Arts during her first two years in New York. In the film, Lassnig’s camera returns again and again to a sculptural bust, resting in the family garden that bears an uncanny resemblance to the artist herself, thus doubling the image of her own body via this inanimate proxy. Slyly comical, Lassnig’s Janus device indicates her application doubling, displacement, and abstraction, visible in her paintings and self-portraiture in photography, into her work in film.

The films on view in this exhibition represent the artist’s meditations on the studio as well as the street. A brilliant example of the latter is Broadway I (c. early 1970s), which documents a theater troupe bedecked in carnivalesque costume and accompanied by percussion and song. It should come as no surprise that performance, whether that of the artist in the studio or the vibrant street cultural performances of Lassnig’s adopted home, became integral case studies of her inquiry into the psychology and composition of the body within space. In Black Dancer (1974), a remarkable 1:20 minute film (which deserves far more analysis than I am treating it with here) incorporates filmic overlay and collage techniques used by both avant-garde filmmakers Richard O. Moore and Stan Van Der Beek in their work with dancers a half-decade earlier.

That Maria Lassnig: New York Films shares the galleries of MoMA PS1 concurrently with Carolee Schneemann: Kinetic Painting drives home a point that both exhibitions seek to clarify: that our study of both these remarkable artists has historically been limited to selected works—or even more egregiously, to media—where their very careers could be case studies in the service of interdisciplinary thought. In pondering Lassnig’s films, it is important to echo Schneemann’s statement that “I consider myself a painter, still and forever (no matter what ‘medium’)”4 in support of an appreciation of Lassnig’s work in film as an extension of—and in some ways a fulfillment of—the concerns that shaped her decades-long work with the body, motion, and paint.

Maria Lassnig: New York Films 1970-1980 at MoMA PS1 runs until June 18, 2018.

- Maria Lassnig, The Pen is the Sister of the Brush: Diaries 1943-1997, ed. Hans Ulrich Obrist (Göttingen: Steidl Hauser & Wirth, 2009).

- Wolfgang Dreschler “About the intimate link between the pained and the painter,” in Maria Lassnig (Wien: Musem moderner Kunst Stifung Ludwig Wien, 20er Haus, 1999), 63.

- Maria Lassnig quoted in Das Innere nach Außen (Amsterdam: Stedelijk Museum 1994), 5.

- Carolee Schneemann quoted in Holland Cotter’s “The Shock of the Nude,” The New York Times February 1, 2018.