Digital Delirium: Pipolitti Rist at the New Museum

by Vanessa Gravenor

Pipilotti Rist’s work is known for her characteristic hallmarks of fusion between digital and cinematic space, between architecture and the body. Most of her work can be characterized by an aesthetic that weaves into feminism, body politics, and sexuality. This aesthetic is comprised of stretched out slow cam underwater shots that jerk the eye and rip apart perception. Though ironically, it is also these aesthetics that obfuscate her politics when not correctly instrumentalized.

These are some of the speculating challenges raised in Pixel Forest, the New Museum’s most comprehensive survey of Rist’s work in New York to date. The exhibition exemplifies what the institution supports, characteristically aimed towards the exposure of the media arts. These institutional politics contrast the display of Rist’s acclaimed Pour Your Body Out by the Museum of Modern Art in 2009, where a main conceptual aim was to feminize architecture through liquefying form, melting down a male modernist aesthetic. At the New Museum, curators Massimiliano Gioni, Margot Norton, and Helga Christoffersen appear to have dealt with Rist’s work also in a similarly subversive architectural manner, though the feminization of the architecture has become lost in the digital sprawl of the works. It remains unclear what Rist is melting at the New Museum, or if the content of her work is melting itself.1 This affects the work with a type of fetishistic quality, where her style has becoming dethatched from any noticeable action.

The New Museum as a whole does not span so much horizontally as it does vertically—comprised of three floors, each containing a different soundtrack. The sonic elements correlating to each work separates the space through defined “soundtracks” made up of melodious sounds sung solely by women. These melodies permeate the air, enveloping the viewer within Rist’s digital delirium, perhaps an example of successfully bringing the viewer away from the confines of architectural space in a subversive feminist manner.

Pixel Forest’s realm of immersive installation touches on a tactic critic Sylvia Lavin calls kissing architecture, where projections merge fully with space, making architecture alien. One such example is 4th Floor to Mildness (2016), where viewers are instructed to remove their shoes before stepping onto plush carpets, then ultimately on beds, in order to lay horizontal to look at the cascade of video projections. These screens are shaped into pond like shapes, mirroring the imagery Rist uses is her video. The imagery in 4th Floor To Mildness consists of water, a common motif that is woven through Pipilotti Rist’s work. This reversal of the ground/ceiling relationship further liquefies one sense of gravity.

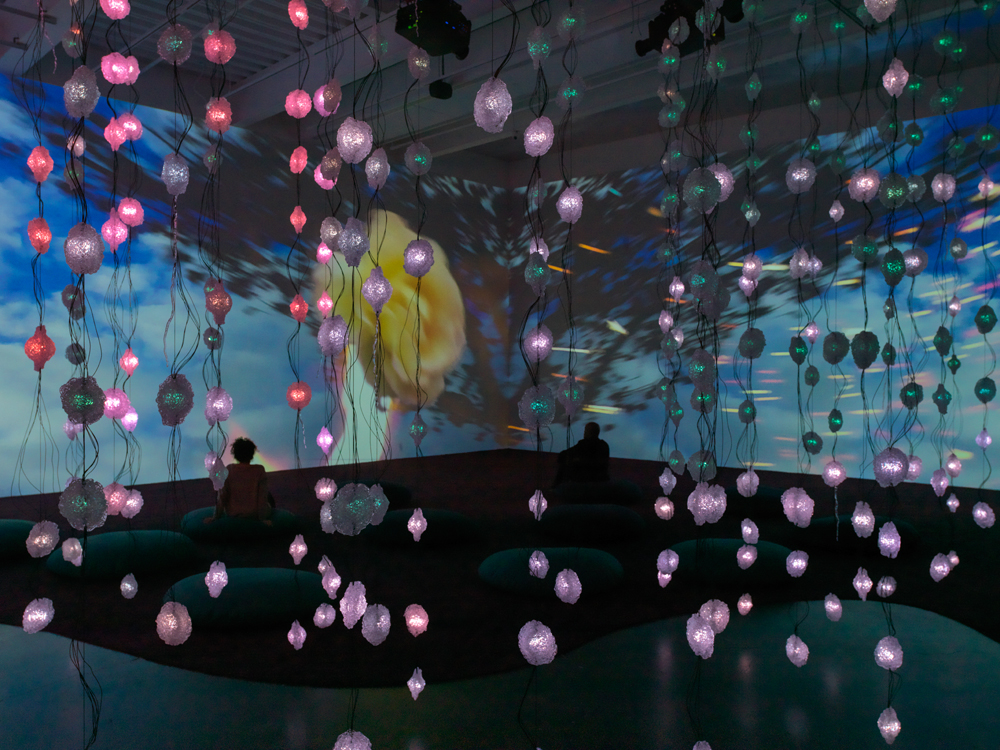

The third floor contains another immersive installation, Pixelwald (Pixel Forest), which consists of Hanging LED light installation and media player. The lights are shaped as natural matter, looking like flowers or wreaths. Pixelwald ironically was also a favorite place among the hordes of visitors to take selfies and Instagram images, which affected the installation with a similar spectacle-like quality as the likes of Yayoi Kusama’s Repetitive Vision (1996).

While the selections of works succeed in enveloping the viewer, the repetition of aesthetics and motifs soon become ubiquitous and stale, so that the image of the fragmented body soon appears as a fetish rather than a subversive statement. Ultimately, the stand-out works of Pixel Forest are the ones that most directly address identity politics through humor. These include Ever Is Over All (1997), where a woman skips down a European Street, laughing and smiling while smashing windows with a flower, and Sip My Ocean (1996), where a woman sings Chris Isaak’s “Wicked Game”, both whispering and screaming the lyrics. In another work, Selbstlos im Lavabad (Selfless In The Bath of Lava) (Bastard Version) (1994), Rist’s naked body has been recorded with the background keyed out. Rist calls out to the viewer, asking them to save her, breaking the typical suspension of cinematic belief. These works are the most poignant in the show, which truly crystalize Rist’s complex and yet digitally auto-tuned conceptual voice, which coyly walks the line of subversion and feminism, while at the same time, creating a cryptically sensuous natural world of sunshine and beaches.

Out of the main canonical works of Rist’s oeuvre I’m not the Girl who misses much, an early work from 1986, which encompasses Rist’s techno-feminist agenda, was noticeably sidelined to small single channel oblivion in a series of sculptural viewing pods lining one of the hallways at the back of the main exhibition hall. This sidelining sums up the main problems with Pixel Forest as a whole, which seems more concerned to pandering to the Instagram artist than breaking down the more difficult aspects of Rist’s work such as her identity politics and her structural technical handle that is often backed by humor. Though as a whole, these viewing pods offered a good opportunity to see Rist’s super-8 works, the viewing experienced became parceled and siloed off to oblivion, whereas the newer works, though expansive, also ended up finding themselves in a frame: the frame of the Instagram filter.

Pixel Forest lived up to expectations, though did not break or add a necessary critical break-down of Rist’s oeuvre. For those already seasoned in Rist’s underwater delirium and pointed humor, the expansive, yet not thoroughly dissected seeming retrospective would appear like any other put-together collection of the artist’s work from the past decades, which has led her to be a pioneer figure in video art. Considering Rist’s style, this had the effect of either appearing too spectacular (an ideal for the Instagram comrades) or entirely flat, summed up to a one-liner about the liquefied body. What seemed to appear as a pluralistic vision ends up fitting neatly into the backlogs of the digital interface of the smart phone, another banishment to a symbolic basement.

Pipilotti Rist: Pixel Forest at the New Museum ran until January 15, 2017.

- In Silvia Lavin’s seminal essay, Kissing Architecture, she claims Rist’s work at the MOMA melts the architecture of the space in a feminist fashion.