Sonic Avenues #2: Ululation

by Patrick J. Reed

The lips, the teeth, the tip of the tongue. The tip of the tongue gives way to the rest: dorsal surface, median sulcus, a blanket of papillae. A swallowing abyss. We have imagined this alien landscape before. Rabelais’s The Horrible and Terrifying Deeds and Words of the Very Renowned Pantagruel King of the Dipsodes, Son of the Great Giant Gargantua (c. 1532–c. 1564) describes a world within a giant’s mouth. Pantagruel’s oral cavity contains meadows and pigeons and cities that fall victim to gaseous plagues. It harbors thieves in the great forests “down by the hinder teeth.”1 The province enjoys life as though it were the quintessential Renaissance landscape, and readers are left to imagine how it might endure gale-force sneezes or violent shouts, or even, if you will indulge the fantasy, ululation—that high-pitched wail modified with an oscillating tongue. A giant’s tongue flicking up and down would certainly wreak havoc. Wild temblor in the plains, the gullet people might call it.

In actuality, ululation heralds no calamity; rather, it expresses joy, sometimes mourning, and sometimes also battlefield rage. One hears ululations the world over, although the Western mainstream pins it, not inaccurately but often pejoratively, to Middle Eastern and Arab cultures. To the uninformed, the warble provokes incredulity, e.g. the mockery that followed what a reporter described as Shakira’s “very tongue-y attempt” at ululation during the Super Bowl LIV halftime performance.2 Amid the online buffoonery, a comment about trying to get the last peach out of a fruit cup transcended the turkey and cunnilingus jokes, if only to confirm that American wit celebrates willful ignorance and that the market for fruit cups is alive and well.

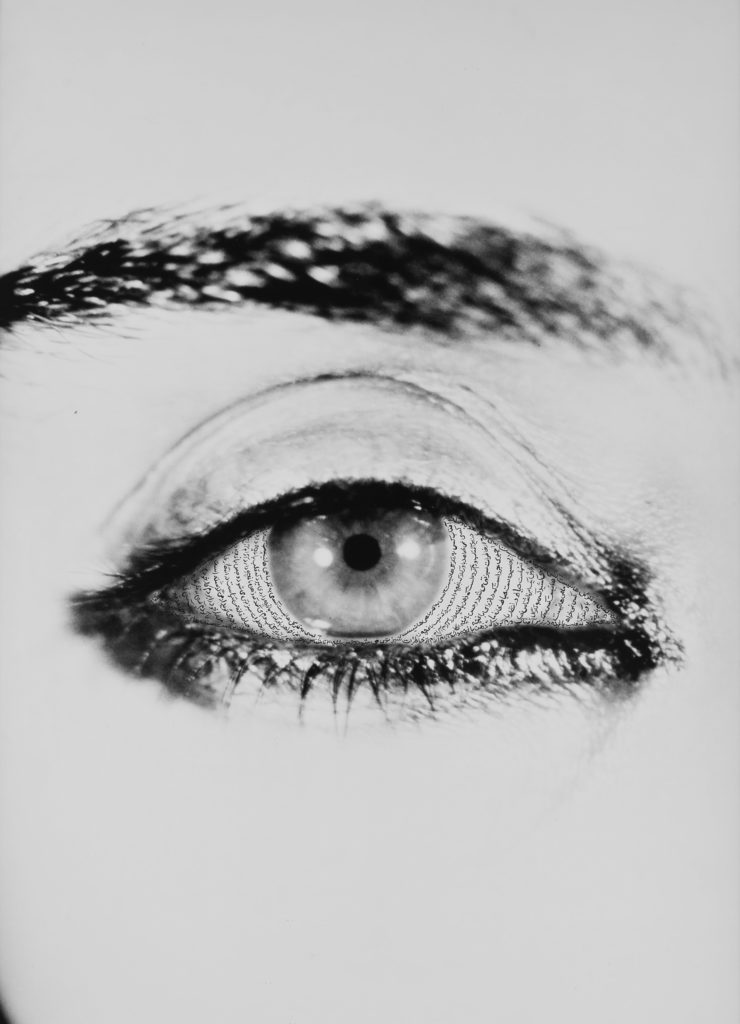

While Shakira’s “gobble” bemused the nation from the Hard Rock Stadium in Miami Gardens, Florida, a similar, albeit more plaintive, sound ricocheted off the walls of the Broad Museum in Los Angeles, where Shirin Neshat’s two-channel video installation Owj [Rapture] (1999) played on loop as a part of her retrospective I Will Greet the Sun Again. Of the works in the exhibition I mention this one, about the earliest, in part for its key moment of ululation and in part because Owj serves as a lydian stone for the Iranian-American artist’s career. It encapsulates the dominant themes of Neshat’s artistic enterprise, i.e. gender in Islamic cultures, archetypal human relations, divisions between collective identities. The action plays out on facing screens. Its narrative unfolds like a myth. On one side, a group of men descend upon a citadel and rally; on the other, women in black chadors emerge from the desert and respond to the men, only to reject them and head for the open sea.

Cultural theorist Hamid Dabashi points out that “there is a sudden rupture in Rapture. Almost halfway through the event, there is an abrupt rising of feminine ululation that interrupts and stops the masculine busy-ness. Men are cast into long shots and women are brought into a close-up. Males are interrupted, females are interrupting.”3 Arthur C. Danto also notes this pivotal moment: “In the work itself, men and women are spectacles for one another, in that the women react to what the men do and the men react to the more decisive action the women take in response to what they see as the deep frivolity of masculine conduct.” He continues, “The women stand in ranks, first looking in what I interpret as incredulous disapproval, then ululating…It is not so much a battle as a conflict of moral wills over what most deeply matters. There are no subtitles, but ululating is a sound of contempt, or even of mourning.”4 By both (men’s) accounts, ululation is a woman’s instrument, an assessment in concert with Neshat’s stark, political allegory of the sexes, and an assessment that reminds us of ululation’s power to amplify user agency.

Neshat’s contrast between men and women, a superficial binary scored by ululation, parallels her equally favored contrast between East and West, a dichotomy likewise accentuated by the sound. Here, ululation is a Middle Eastern interjection, loud and proud; it is the sharpest expression of a difference integral to her heritage and exaggerated by foes, a condition, one might argue, of double consciousness. Her biography as an artist exiled in the United States during the Islamic Revolution in Iran and its subsequent war with Iraq provided the fodder for her early photographs and videos, including Owj.5 With these works, she attempts seizure of a complex identity jeopardized by socio-political upheaval—a specifically female, Persian identity in danger of erasure by the fundamentalism within Iran and the Islamophobia knocking, still knocking, at its door.

The near diplomatic meltdown caused by the American drone-strike killing of Iranian Major General Qasem Soleimani on January 3, 2020 hyperactivated the perennial East-West rivalry, and, by extension, the timeliness of I Will Greet the Sun Again. Neshat’s work thwarts contempt for cultures of the MENA region, and, in light of Trump’s threat to target Iranian cultural sites should the country avenge Soleimani’s death—a threat that failed to materialize after Iran launched missiles at U.S. forces in Iraq a few days later, not least of all because such action would have constituted war crimes—its institutional presence in the American body politic is all the more necessary.

On the home front, we find the vainglorious side of Trump’s threat manifest in the “Making Federal Buildings Beautiful Again” executive order, a directive (in draft form at the time of writing) that requires neoclassical designs for future federal government buildings, something akin to heritage sites for the Fruit-Cup Generation. The implications of this potential legislation are shameful. It is as if we learned nothing from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Michael Kimmelman put it best: “…the order provokes inevitable allusions to authoritarian regimes of the past that imposed their own architectural marching orders, and dredges up images of antebellum America, when classicizing Federal architecture was all the rage. Associations like these might sound extreme; but then, so does the order.”6 I would argue that Kimmelman’s associations are right on point. The MFBBA (or whatever) would set a precedent for erasing America’s cultural diversity as reflected in its built environment and lay the foundation, so to speak, for a domestic cultural decimation as tragic to global heritage as the burning of any great library.

Tradition should not mean contraction. We should build our diversity diversely, sound out our differences in unrestrained trills. Wild temblors! We should wish for seven tongues, like Rabelais’s monster Hearsay, but wish to use them as Neshat’s women do—in protest. Seven tongues to decry the day, to ululate seven-fold against horrible and terrifying deeds and words.

Shirin Neshat: I Will Greet the Sun Again ran at the Broad Museum from October 19—February 16, 2020.

- Francois Rabelais, Five Books Of The Lives, Heroic Deeds And Sayings Of Gargantua And His Son Pantagruel (c. 1532–c. 1564; Project Gutenberg, 2004), bk. II, chap. 2.XXXII, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1200/1200-h/1200-h.htm#link22HCH0031.

- In reference to Shakira’s on-camera uluation, said reporter, Dahlia Bazzaz of the Seattle Times, used the term “zaghrouta,” which is a celebratory application of ululation in Arab culture. Allyson Chiu, “‘It’s not a turkey call’: The cultural significance behind Shakira’s meme-worthy ‘tongue thing’ at the Super Bowl,” Washington Post, February 3, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/02/03/shakira-tongue-superbowl.

- Hamid Dabashi, “Bordercrossings: Shirin Neshat’s Body of Evidence,” in Shirin Neshat, ed. Giorgio Verzotti (Milan: Edizioni Charta, 2002), 53.

- Arthur C. Danto, “Shirin Neshat and the Concept of Absolute Spirit,” in Shirin Neshat (New York: Rizzoli, 2010), 11.

- This turbulent era in Iran’s history occurred from 1978 to 1988. Although Neshat arrived in the United States in 1975 for the purpose of study and did not visit Iran again until the 1990s. Following an incident in 1995, when she was detained at the Tehran airport and interrogated by the authorities, she returned to the United States, where she remains in exile.

- Michael Kimmelman, “MAGA War on Architectural Diversity Weaponizes Greek Columns,” New York Times, February 7, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/07/arts/design/federal-building-architecture.html.