Profile of the Artist: Ursula Biemann

by Vanessa Gravenor

Reversing Information Flows: Forest Law and Deep Weather

Ursula Biemann is a Swiss video artist whose work focuses on the neocolonialist, exploitation of resources, with all its deleterious affects on the Global South. Within her video essayist practice, Biemann contends with the value of the body—its eradication to what Giorgio Agamben calls “bare life”—in the face of industrial systems where resources are valued more highly than life. Her subjects are changing ecologies, figures that threaten labor populations in the Global South, and foreclose the possibilities of future life. Biemann’s tactics make use of a combination of fieldwork, theoretical research, and collaboration with artists, sociologists, and anthropologists. On view in Montreal at the Leonard & Bina Ellen Gallery till April 18th, I was able to view a video essay Forest Law on a trial surrounding the rights of the indigenous people over the land of the Ecuadorian Amazon.

Ursula Biemann earned a BFA from School of Visual Arts in New York City, and was a participant in the Whitney Independent Study Program. Among her early projects include a video essay project called Performing the Border, which documented female Mexican Assembly labor. Within the last decades, Biemann has focused on the overlap of boarder and migratory zones with corporate exploitation of oil by going directly to the sites where the resources are mined. Biemann can be grouped with other artists from the early 2000s who, as Dieter Roelstraete has explained it, use anthropology as a means of their art work.1 Yet, unlike the alternative “History Channel” that Roelstraete claims as characteristic of these artists / anthropologists, Biemann offers viewers an alternative News Channel. By opposing newsroom settings, catchy headlines, and the trope of “reporting” by reversing typical information flows, Biemann’s videos allow information to flow from the sites in question, and give space for the future to stand as a co-shared zone. The land and the subjects who testify in her videos ultimately become witnesses stuck in an undercurrent of global practices that are founded in a not so distant colonial past.

Biemann’s practice underscores the after-modern and what Zygmunt Bauman calls the liquid modern times that created a notion of globalization flattening all sense of locality in the liquefying flow from Empire to Democracy. In Biemann’s case, this liquidity takes on a material form as the very real flooding of lands as a result of changing ecologies.2http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3786078/3

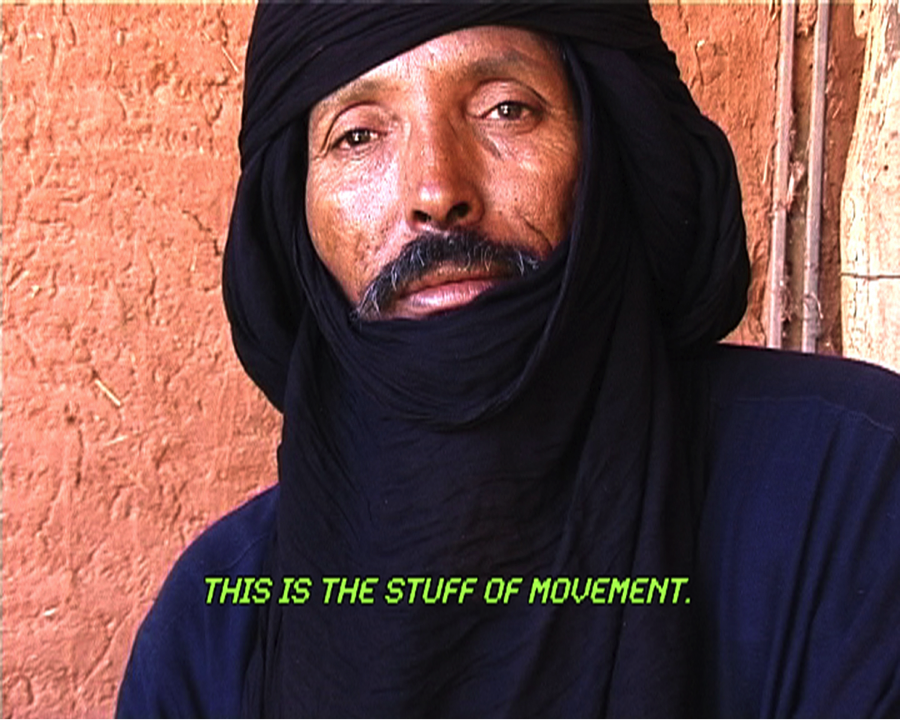

Many of her video essays, such as Forest Law (a collaboration with Paulo Tavares), Black Sea Files, and Deep Weather begin with an exterior glimpse of the local land she then magnetizes. In this way, Biemann is constantly going from a general language above the body of her subjects (land politics) to showing the personal faces of laborers and advocates. Both Deep Weather and Forest Law include voice over spoken word offering poetic and yet startling observations told from the distance of a helicopter plane or what appear to be drone imaging. In Deep Weather, she whispers the text—her voice takes on something of a hysterical or quivering sound as she recounts stories of violent deaths that become embedded traumas within the mutating land.

Forest Law explores the Ecuadorian Amazon people of Sarayaku and their recent court case where the indigenous people argued for the rights of nature. Central to Biemann’s practice is the concept of citizenship, focusing on figures that might live as nomads or in states of precarity. In this video, a Sarayaku leader explains that while the government categorizes his people as impoverished, this categorization for wealth does not take into account the wealth of the land that the people have learned to live symbiotically with. The Sarayaku leader says, “this land is our life”—suggesting that the land should have rights on par with citizens.

What becomes very clear over the course of the video is how incompatible the formalities and classifications of global culture are with the viewpoints of the Sarayaku people. The leader explains how explosives for oil prospection were buried in the forest, but never detonated. Falling into a Class C, the explosives can be left in the land, as they are deemed not dangerous because of how far away they are from people, thus having no direct threat on life. However, this is in absolute conflict to the Sarayaku and their reality—the forest gives them life, and is a being that in itself gives them their home and territory, not simply an industrial provider of resources.

Throughout the video, although the indigenous voice is central, there are interspersed images of scientists that seek to archive different plant species. While this might be a typical planning for the future by creating a comprehensive study and archive for the past, Biemann acutely notes that as these scientists plan for the future of botanical classification, there might not be a present for them to found their future on.

Another video project, Deep Weather, focuses on laborers living in Bangladesh that work to keep their eroding shoreline at bay. In her hushed and whispered spoken word text, Biemann shares violent events of populations—not individuals—being drowned in their sleep. Here, once again, we see the space of the living as becoming inhospitable do to “a constantly fluctuating mobile mass,” which is the land in a state of crisis.

Although Biemann’s video essayist practice focuses on elements of stark reality, what all the videos subtly hint at is the artifice of the architecture of wealth that is accelerating nature into states of oblivion. In many ways, she implicates herself through her own voice, through her own privileged accounts are told from a distance. She reminds the viewers in the gallery, who are probably sitting in a museum or academic setting, how modernist viewpoints of global progress not only still persist, but are also becoming more virulent and blinding.

Ursula Biemann’s Forest Law in collaboration with Paulo Tavares was part of a traveling International Arts Exhibition Project World of Matter that was recently on view in the Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery at Concordia University.