Sable Elyse Smith: Men Who Swallow Themselves In Mirrors

by Natalie Hegert

The United States has the highest rate of incarceration in the world. It is a statistic we have become accustomed to hearing. But those numbers leave out the reality, the impact, and the imprint of the carceral state—what Ta-Nehisi Coates terms “the Gray Wastes”1—on the social fabric of the country, on the landscape, on individual bodies.

The geographic impact alone is startling. A series of aerial views of prison facilities recur in many of artist Sable Elyse Smith’s works: ordered, gray, low-slung Corbusian ziggurats flanked by parking lots, surrounded by rural fields and desert runoff, in extreme isolation. In such a landscape, the individual is disappeared, made invisible, subsumed by the power of the state.

Smith’s work, recently highlighted in a major solo exhibition entitled Ordinary Violence at the Queens Museum in New York, addresses the institutional and often invisible or normalized brutality that seeps through the systems under which we live. In fragmented visions that oscillate from intimate anecdotes, to appropriated blips of music and video clips—from words to images, from narrative to non-narrative— Smith interweaves personal experience with power structures. In her videos, the subject is often absent or just out of the frame, voices get interrupted, the song cuts out just before the groove.

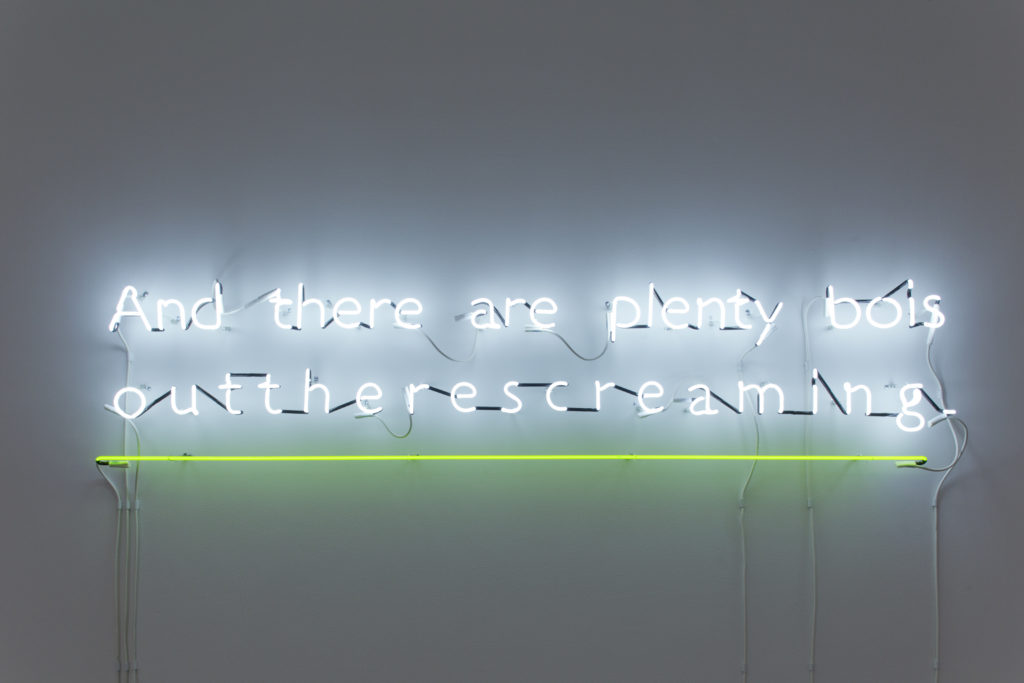

Natalie Hegert: At SITE Santa Fe, you are showing a newly commissioned neon work, the fourth of an ongoing series of neon text works entitled, somewhat incongruously, Landscapes. Owing to neon’s prevalence in commercial signage, many neon text works often come off as a vehicle for slogans, amounting to glib oneliners. Your neon works, on the other hand, operate in a different, more enigmatic way, employing poetry to suggest an image or feeling—the words working more on the level of affect than concept, perhaps. There is a tension in these works between the intimate subject matter and the neon as a format for public signage. As a writer, how do you, essentially, write for neon? What initially attracted you to neon as a medium?

Sable Elyse Smith: In these works, I am not necessarily writing for neon. I am writing—and versions of these texts, or fragments, become neons. Yes, our quotidian association with them may be from signage, but they also have a significant art historical reference. The medium of neon was selected for a number of reasons, particularly its materiality. It operates in the realm of seduction; there is this sumptuous quality to it. Obviously, this deals with light, and this light is presented as sexy and seductive, but in actuality it is a sickly light. It is harsh and artificial, and the color of the skin is altered underneath it. It hints to an institutional light and the light of advertising at the same time. The longer you stare at it over time, the harder it becomes to look at. Another very important, yet subtle, quality of neon as a material is its buzz—a sound that is emitted almost undetected at times, or that threads itself to the other ambient sound in the room so much so that it begins to seep into you. Often, it is only when it is no longer present that you feel it. This buzz is a repeated motif in my work to talk about that quality of invisibility. NH: Why are they “landscapes?” You have talked about your neon works in relation to painting and the Hudson River School; how do they figure into that history?

SE.S: The neon works gesture to multiple definitions of the word landscape, and wrestle with the genre of Western landscape painting. A genre that is obsessed with light. The neons are all horizontal in orientation, and the underscore of the text visually renders a horizon line. The neon as a whole—meaning its materiality, color, and the content of the text itself—all paint simultaneously different “landscape images.” Here, I am using the term ‘landscape’ loosely, as a dreamscape, a psychological landscape, etc.

Queens Museum, and JTT, New York. Photo Credit: Hai Zhang.

With the landscapes depicted within prison visiting room murals, aerial photographs of prison complexes, or the landscapes of the Hudson River School, for example—in each of these images, there are bodies being disappeared, and a machine behind that disappearance. My landscapes take us back to the body.

NH: Does that connect to the use of Charles and Ray Eames’ Powers of 10 (1977) in your video work Men Who Swallow Themselves in Mirrors (2017)? How does scale operate as a device throughout your work?

SE.S: This definitely connects. The inclusion of that Eames’ film was of course to talk about scale, as well as to directly question one’s way of looking at the content in my film—and in media content in general—since Men Who Swallow Themselves in Mirrors appropriates media from our contemporary pop cultural sphere. In this sense, the installation asks you to question the context around the image one might be consuming at any moment, and to really think about its implications if you scale back by “powers of ten.”

NH: Your work deals with the prison system in the United States, and its impact on the landscape, the psyche, the body, and the communities affected by mass incarceration. Your series of coloring book paintings offers a glimpse at the experiences of the most impressionable constituency affected by the prison and court system: children. How did your experiences of visiting your father in prison affect you, both as a child, and over time? You have described the way that your body reacts to entering the architecture of the prison, how your posture and voice change in response, as a kind of quotidian violence that accumulates in the body over time. Does your work serve as a way to reclaim agency in the face of this authority?

SE.S: My work is concerned with asking us to take a sharper look at the systems governing our lives and the language we use—and are socialized to use—to describe and re-inscribe certain systems and individuals. My work inherently privileges the body. In relationship to prison it is aiming to add complex narratives to the landscape of stories told around carcerality. And the practice’s focus is on highlighting humanity.

The fascination for me with the coloring book works is the way that language and image function within them; the racial implications of a black and white line drawing, and a camouflaged or inadvertent foreclosure of imagination. This is a suggestion that is dangerous in any space—not just the prison/judicial space. What happens when we accept and internalize a specific type of language?

2017-2018. Courtesy of the artist, New Museum, and JTT, New York. Photo Credit: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio.

NH: In making your work, you necessarily have to navigate, work with, and against, the institution of the prison system. How would you define your relationship to the institution of art—is there a struggle to work with and against that institution as well?

SE.S: I make deliberate decisions about what institutions I engage with, and in what context that engagement takes place. These are things that I do not compromise on. The many facets of my art and education practice operate within and outside of the institution of art and that is important to me.

My allegiance is not solely to operating in the space and context of the white cube. The stakes for the questions I am asking in my practice are a lot higher.