Profiling the Experience of a Residency: Spring Residents at Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts

by Joel Kuennen

In April, I flew over a bloated, sluiced Missouri River to Omaha, Nebraska to be THE SEEN’s first Critic-in-Residence at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts. I emerged from the sandstone-colored airport to meet Davina, their Communications Director, who ferried me past the former Conagra headquarters that sprawls around the public Heartland of America Park to one of the largest and most well-known residencies in the Midwest. Housed in a former bag factory, one of many large brick warehouses that take up a majority of the old market area of Omaha, Bemis feels like space incarnate. These warehouses are immense sienna stellae, divided by patchwork pathways of cobble, brick, and blacktop—buried veins of track break the surface occasionally, reminders that Omaha was once the transportation nexus to the West and the site of the largest stockyards in the US. A refrigerated warehouse still operates across the street from Bemis, its compressors and fans the size of semi-trucks humming day and night.

I was given a key and shown to my room, one of the visiting artists rooms that looked east to the KANEKO, an excellent museum dedicated to ceramic sculpture and home to Jun Kaneko’s studio. I walked to the nearest gas station/grocery shop, Cubby, and got some basic groceries to cover the week and settle in. I immediately met a loose cohort of the residents unwinding after a day in the studio—Kandis, Rodney, and Adam—and joined them next to the workshop space to share a drink. Eventually, the rest of the residents migrated into the circle, sharing tips and sips of wine and beer that remained from the three-month residency that was now nearing its end.

The next day, hickory smoke moved slowly through the cold air, wafting down from Cubby where a grillmaster had set up shop for the morning. I met with the newly appointed Chief Curator and Director of Public Programs, Rachel Adams and wrote, taking advantage of the quiet space and refining isolation of new surrounds to get some work done. I noticed a pigeon corpse eviscerated and left on the awning outside my window. Hawks use the brick stellae as perches to hunt city squab.

Irini Miga

My first visit was with New York-based, Grecian multimedia artist Irini Miga. Miga showed a new series of work, engraved scissors stuck into the grout lines of the cement floor of her studio. The scissors were etched with words that connoted the abstract function of demarcation. Her smooth concrete floor, an expanse of uniform gray, was now in the process of being cut up into a series of patches. Their qualities and their positions in relation to other elements of the room were now somehow more important. This patch was next to the restroom, that one has full sun for most of the afternoon.

Miga works through poetic transpositions and gestures that destabilize expected meaning. Grounded in poetics, Miga explores her humanity in fabular ways, constructing object narratives that relish meaning-making as a fundamentally aesthetic experience. For the resident’s exhibition, Miga created a work that began with Blake’s Ancient of Days and the span between the thumb and forefinger of the god figure that reaches down from a glowing orb into the void. Miga measured the distance between her own thumb and forefinger, the arc of that distance was then carved into drywall and filled with a glazed ceramic piece. The arc then reappears on the wall, two arcs facing each other. All of creation is along those arcs, between two fingers.

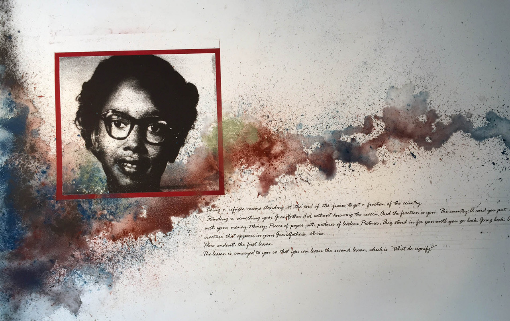

Rodney Ewing

After grabbing lunch from Cubby’s grillmaster—tangy ribs and sticky-thick mac and cheese—I met with San Francisco artist Rodney Ewing. He was beginning to sort out an installation strategy for showing a new series of works on paper that explored extreme violence against Black communities and their consequential cultural responses. The works move from the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, which re-emerged recently in popular culture thanks to an intense opening-scene of the HBO show, Watchmen, depicting the burning and bombing of the Greenwood neighborhood, the wealthiest Black neighborhood in America at the time, to the 1985 bombing of the MOVE house in Philadelphia where an incendiary device was dropped from a police helicopter onto the Black liberation group’s home, leading to a fire that burned 65 homes.

Ewing translates the horrors of racialized violence into abstract lines, connecting archival images to the broader contexts that are marginalized by the gaze of history. In doing this, Ewing does not abstract these violent acts, but points back to the real consequences obscured by the abstractions of history.

Jes Fan

After a short break, I ran downstairs to Fan’s studio. On the gray floor lay a white fur blanket with ceramic nets cast as low forms cradling glass spheres in which small black dots of melanin sat still, frozen inside the crystalline glass. Printed paintings by Lam Qua, a Chinese painter who specialized in Western-style portraiture and was hired by an American doctor to document bodily deformities before he operated, lay on the ground and pinned to the wall. Many of these paintings are held by Yale, and Fan planned to visit the archive following the residency.

Support structures made of clay, like deformed jungle gyms, were affixed to the walls, and drooping clear glass balanced on the supports. Fan’s work often begins with the body, moving outward to its cultural implications. His works manage to balance between soft and hard, grotesque and cradling. The body, its signifiers and markers, are both concrete and ever changing, the melanin of our skin darkens and lightens, tumors and cysts can bulge under our skin, to either resolve or be cut out. Each state of our body forces us to contend with the concrete reality of our existence within it and develop structures to support it and ourselves.

Adam Milner

The next day, I had the slow pleasure to begin with Adam Milner’s archaeological work. A voracious collector of personally meaningful objects (sometimes sourced from friends), Milner carves supports in rocks or felt-lined depressions fitted for each object, sometimes displaying the objects like museum pieces, other times displaying only the supports like empty ring boxes—using the object’s void to communicate the care that remains after distance or loss.

Milner has used blood as a medium for the last four years. He dyed a pair of seersucker tuxes with his and his partner’s blood and used his own blood as an ink to create paintings on paper. Over time, the blood continues to oxidize and transform. Most recently, over a random conversation with an engineer, he discovered that NASA fabricates fake moon rock to run tests on. The binding ingredient in these approximated lunar regoliths is bovine blood albumen. The brick of regolith in his studio contained a retainer and a novelty rolled penny embedded within the black-gray aggregate. Artifacts from his life, fossilized.

Melanie Mclain

Walking into Mclain’s studio, I see two cream-colored laminated composite wood sculptures attached to the wall just below waist-height. Smooth dips are carved into the cubes. Mclain lifts her knee and twists her leg towards her pelvis, her knee glides into the depression and settles there. A performance artist who creates structures to determine her performers movements, Mclain walked me through her social architecture work: a chin rest, a buttcheek rest, a finger rest, a desk with two cubbies and zippers secure the performer to the sculpture via a matching zipper on the performer’s jeans.

Mclain’s more complex sculptures, like the one that was installed at Socrates Sculpture Park between 2015 and 2016, position performers in uncomfortable positions—often stances and configurations that require the support of another performer to maintain. We talked about this seeming desire to punish the performer, to create difficulties in navigating social structures. The twists and contortions are beautiful, however.

Cameron Granger

Cameron, a filmmaker and multimedia artist from Cleveland, Ohio, installed four elementary school desktops on the wall of his studio. On the flat desks, four mapped projections showed clips Granger sourced from Youtube. Granger was exploring improvised cultural resistance to modes of reeducation, localized to Black kids growing up in an American education system that rewards Euro-centric conformation. The videos showed beat-making, cars doing donuts, singing and rapping, and title cards from Bad Boys (1995), Don’t be a Menace (1996), and Boyz n the Hood (1991). This work was later shown in an expanded formation in the Columbus Museum of Art’s Greater Columbus 2019 exhibition, curated by Danny Marcus, and included scenes from Dylann Roof’s confession. There is jubilance despite the context of racist mass murder and movies that present a violent vision of a community to itself. Jubilance can be an extremely effective form of resistance, creating a counter narrative to the oppressive visions from without.

Next to this, Granger had a large image printed of his father’s back. He was wearing a motorcycle jacket standing next to his hog. Granger did not know his father well and this image is one of the few he has of him. It acts as somewhat of punctum for him, albeit one he has trouble describing; his father sits as an image in his mind, unresolved, unplaced. Next to this image, a mirror with an engraving of his father’s face is barely visible behind one’s own reflection.

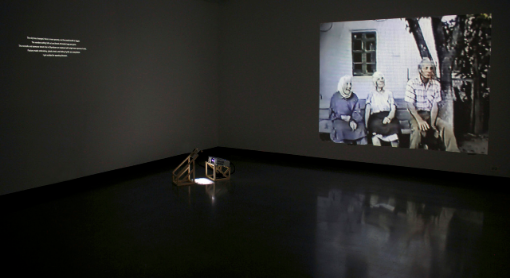

Kandis Friesen

Friesen grew up Russian Mennonite in Canada. This sect of Anabaptism still speaks a form of low-German called Plautdietsch that dates back to the group’s religious persecution and exile. This language itself is both insulating and a point of continuity reaching back into the distant past. Kandis’ family, originally from the Germanic lowlands, migrated East to Prussia, and was then drawn by Russia to settle the Ukrainian steppe after the fall of the Ottoman Empire. Following the Bolshevik Revolution, many Mennonites were dispossessed of land and after WWII the foreign, German-speaking minorities were sent to labor camps in Siberia and Kazakhstan. Friesen’s family emigrated to Canada after the fall of the Soviet Union, though she still has relatives in Kazakhstan and Germany.

Friesen’s practice ranges from blowing up details from family pictures and postcards, hyperfocusing on printing patterns and expanding the prints into new landscapes, to recreating ceramic tiles that resemble the asbestos roof tiles produced in Canada and used in Ukraine. Her practice is deeply informed by ethnographic and genealogical research she has conducted during successive trips to Ukraine. On one such trip, Friesen became enamored with the knockoff plastic shopping bags that are everywhere in Ukraine, seen as status symbols, these disposable bags with slight variations of luxury logos are an aspirational conjuring. In 2018 Friesen created a series of inverted BMW bags called, DAUT DINTJ DAUT HELT, Plautdietsch for “the thing that holds.”

Marc Vilanova

For the resident exhibition, Vilanova, created an ambitious installation, Spike, that attempts to visualize the “mind” of an AI. To do so, he and his studio assistant broke down yards and yards of a 40 pin ribbon cable, the point of connection between the motherboard and peripherals, like external drives. Each strand—14,200 of them—was hung from a large wooden U creating an encircling forest of dangling cables. Some 200 of the cables were then wired with varying intensity LED lights. The LEDS responded to an evolving score based on a feedback loop the artist created. This loop was based on the artist responding to his own work via an encephalogram (EEG). The light and sound of the installation are generated by the parallel patterns recorded by the encephalogram.

Vilanova’s work ranges from experimental saxophone performances that are mesmerizing in their beautiful misuse of the instrument to light and sound installations like the complex Spike. The recurring loop, a concept Vilanova was toying with at the time of our visit, can describe his broader practice wherein a sound, light, and tech visualize the arresting improvisations that both define and drive creative intelligences.

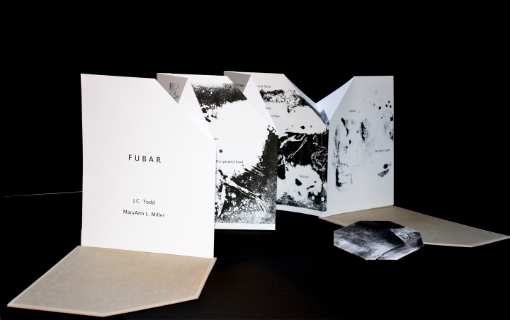

J.C. Todd

My final visit was with the poet and activist J.C. Todd. Todd hung a series of woodcut reproductions by Käthe Kollwitz around her studio from the series Krieg. The series of seven gaunt reflections on the human sacrifices of WWI, specifically those left behind—women, children, the orphaned and abandoned—stood as points of contemplation for Todd to respond to. “There’s a narrative of greater good / as if motion has a direction” begins one response. Todd’s work, including her artist book FUBAR (2016, 2018), questions the connection between progress and war. How has war become an inevitable entreé to progress, like its ensuing erasure is somehow a pretext to the foundation of an order that is deemed progressive?

Todd’s style is visceral. She connects the ideals of glory to the bodily consequences of aspirations, the feelings between us, the touch of a mother: “mother’s hands are / palm snugged to skull / ear muff of tendon”. Her words are taut, the sinew of human connection straining against our worst impulses.

At Bemis, I joined an impromptu community for a few days and felt the joy of exchange that had developed between these artists. Their works seemed to wind in and out of each other, informing and emboldening each other. I would like to thank Rachel Adams and the staff of Bemis for their generosity in hosting me and opening the door to the beautiful world they facilitate, season after season. Thank you to each artist—Irini Miga, Rodney Ewing, Jes Fan, Adam Milner, Melanie Mclain, Cameron Granger, Kandis Friesen, Marc Vilanova, and J.C. Todd—for sharing their work, sips and tips, and their research with me.

All images via the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts’ 2019 Residents Website.