Unbound: Contemporary Art After Frida Kahlo hails Frida’s role as a harbinger of art and politics of the present. Her practice is encapsulated through current cultural politics and the performativity of gender – depictions of the body in this exhibition could be seen as acted upon by politics, and the industrial practices that spawned globalization. Kahlo’s first exhibition in the United States was at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago in 1978, and so it is quite fitting that a context of contemporary art framed after her revolutionary legacy in Unbound should follow suit.

For Kahlo, distinctions of gender and sexual preference occurred within a spectrum – as spaces in flux – they were never fixed markers. In 1993, Judith Butler wrote about the performativity of gender in Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex,” stating that it is “a discursive practice that enacts or produces that which it names.”1 This statement establishes that the activity of assigned gender has been and is, in of itself, a performance. Similarly, in 1990, Arjun Appadurai coined the term “mediascapes,” which is defined as something that “…indexes the electronic capabilities of production and dissemination,” and contributed to “…images of the world created by these media.”2 What this essentially refers to is a world of globalized images – these cycled tropes are found in advertising, books, magazines, television, and cinema. Prior to the creation of such terms regarding globalization – but also queer, and networked imagery, Kahlo’s work served as the subversive anchor for these upcoming social and political developments.

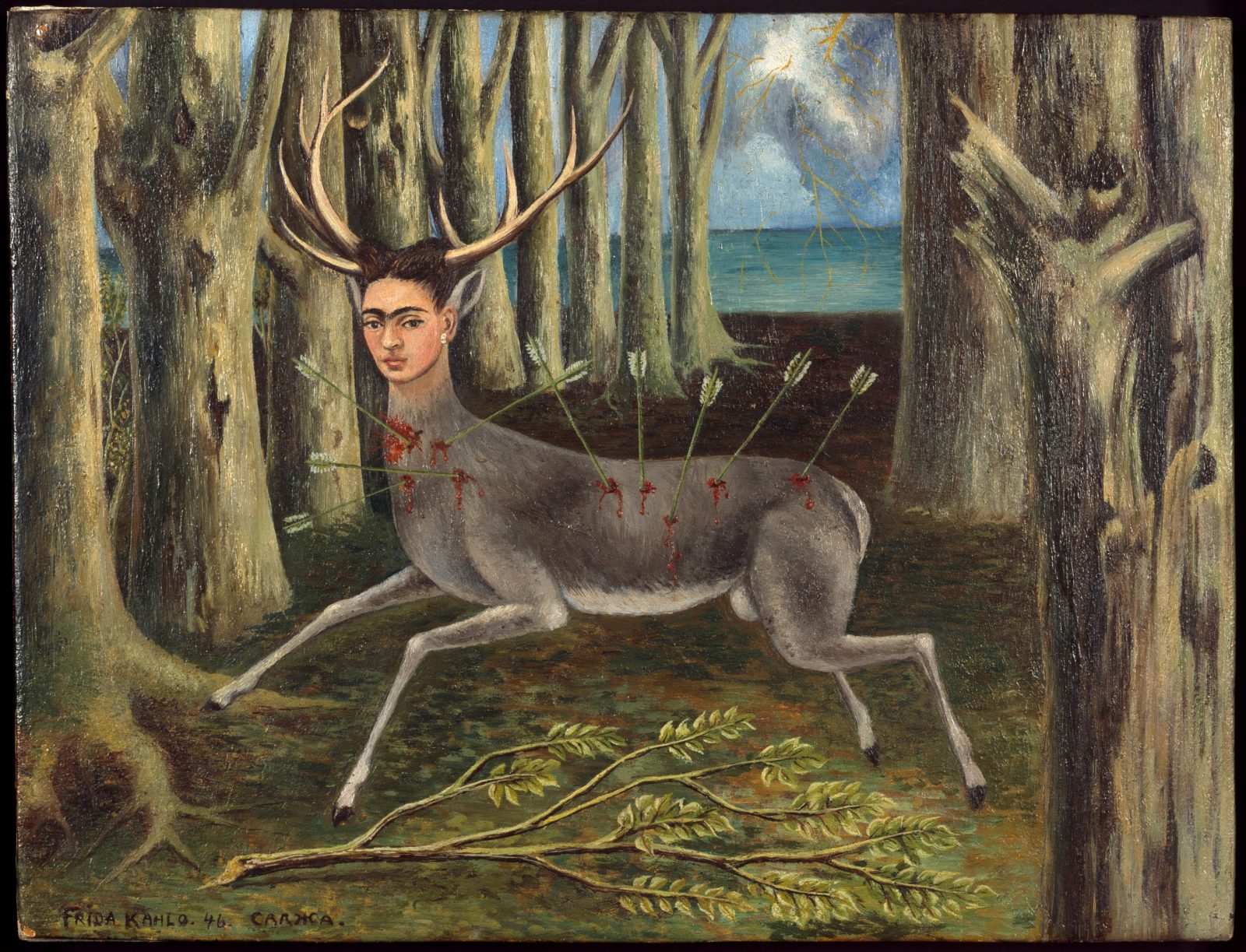

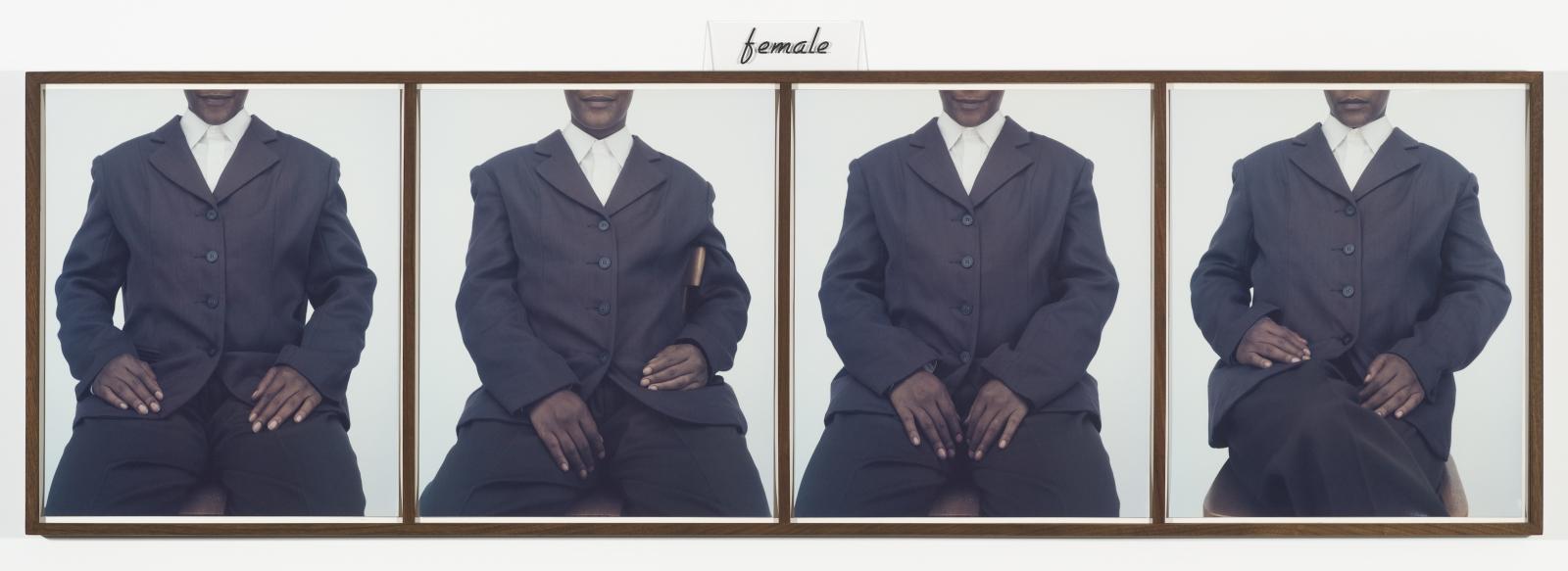

This exhibition only features two of Kahlo’s paintings, Arbol de la Esperanza (Tree of Hope) and El Ventida (Little Deer), but includes 31 other artists’ work. Unbound is loosely divided into four spaces – the political body, the absent or traumatized body, contesting national identity and performing gender. When one enters the exhibition, the bright red wall in the middle draws them into the space. Placed on the floor are a few sculptures, one is The She-Fox by Louise Bourgeois, a 6-foot sculpture made of black marble and steel – an aggressive treatment that takes the figure, and challenges traditional definitions of “femininity” and also depicts Bourgeois contested relationship with her mother. The truncated sculpture transforms the body, adding breasts, removing the throat, hybridizing with a fox’s body. Although the female form is apparent, it is rendered mutilated as Bourgeois bust is placed in her haunches.3 Following this piece are the color Polaroid series of photos, She by Lorna Simpson, which inverses categorical assumptions of gender. While the work is titled She, and the engraved Plexiglas placed on top of the photos reads “female,” the masculine dress and postures of the figure signal the ambiguity of such distinctions. In the posterior of the space, a dual projection and a reverberation of the singing voice is heard. Upon closer inspection, Turbulent by Shirin Neshat addresses Iranian Islamic Law that forbade women to sing before a public audience. Polarized by gender, an all male audience gazes out into the audience while a woman sings in the opposite projection.

Described as “unfixing categories of gender, referring to them as constructions of culture,” the type of conversation cited in the release might seem blasé, or approached by some with indifference. But that attitude would fail to grasp the historical and socio-political condition in which these artists made their work. Indeed, while Kahlo’s work functions as a type of signal for the upcoming international struggles of liberation – of civil and women rights for future generations – her revolutionary spirit paired with the artists in Unbound questions the hegemonic “predominance of straight, white, male perspectives” in the contemporary art world, and beyond.4

Unbound: Contemporary Art After Frida Kahlo at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago runs through October 5, 2014.

- Butler, Judith. Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of ‘Sex’. New York: Routledge, 1993.

- Appadurai, Arjun. “Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy — Appadurai 2 (2): 1 — Public Culture.” Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy — Appadurai 2 (2): 1 — Public Culture. Duke Journals, n.d. Web. 21 May 2014. http://publicculture.dukejournals.org/cgi/pdf_extract/2/2/1.

- Bourgeois, Louise, Marie-Laure Bernadac, and Hans-Ulrich Obrist. Destruction of the Father Reconstruction of the Father: Writings and Interviews, 1923-1997. Cambridge, MA: MIT in Association with Violette Editions, London, 1998. N. 140. Print.

- Widholm, Julie Rodrigues, and Abigail Winograd. “Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago.” Unbound: Contemporary Art After Frida Kahlo. Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, n.d. Web. 21 May 2014. http://www.mcachicago.org/exhibition/unbound-contemporary-art-after-frida-kahlo/.