In late 2017, the queer media outlet them. released its inaugural video for Sister, Cister, featuring the writer, curator, and activist Kimberly Drew and the scholar, filmmaker, and activist Tourmaline Gossett.1 As Drew and Gossett sit in a pristine nail salon, the two dip their heads towards one another in a kind of cosmetology communion, discussing identity, gender performance, and ally-ship in calm, reassured tones. A month earlier, Gossett had posted a scathing Instagram update naming David France as the director who had stolen her hard-won archival research and cinematic preparation for a film on Marsha P. Johnson, a concept France then turned around and sold to Netflix. Over the course of the short video, Drew and Gossett keep returning to the notion of “messiness,” of permitting oneself, among all intersections, to be messy.

It was this idea of messiness that stayed with me as I stood over Kellie Romany’s In an Effort to be Held (2016) at the DePaul Art Museum’s Out of Easy Reach. An ambitious endeavor, Out of Easy Reach is a tripartite exhibition held between the DePaul Art Museum, UIC’s Gallery 400, and the Stony Island Arts Bank. The exhibition’s thesis is as ambitious as its organization; DPAM’s gallery alone stakes its claim on the body, the archive, and landscape under the larger exhibition umbrella of abstraction as a method of navigating visibility and identity for Black and Latinx women-identifying artists. But as I gravitated towards Romany’s installation, I was not thinking about whether the exhibition could withstand the weight of its own (admirable) audacity, or if such a broad scope in topic would undercut the potency of the included works. Instead, I was thinking about messiness.

In an Effort to be Held is a cluster of small ceramic discs arranged on a rectangular white table, pressed widthwise against the entry wall of the exhibition. The center of each ceramic disc has been carefully stained with varying concentrations of oil paint mimicking the shades of skin tones, ranging from deep brown to diluted ochre. At the far end of the table, two sets of white gloves have been laid out with their fingers pointing towards the stained ceramics. Visitors to the gallery are invited to slip on the gloves and gently handle the discs, inspecting their textures and tones on a more intimate register. The simple act of handling these palm-sized pieces is like conjuring up an endless backlog of connections. On one end of the spectrum, Romany’s work calls up the image of a refrigerator replete with circular petri dishes of Henrietta Lacks’ cells, just one instance in a history of segmenting P.O.C bodies for study and consumption. On the other end of the spectrum, are rows of rounded pigment vials used to create Fenty Beauty’s complexion-inclusive foundation line, a sharp addition to the beauty market for the visibility of people of color. From Tuskegee to Lorna Simpson, Romany’s In and Effort to be Held prompts the viewer to consider her ceramics from every angle, and simultaneously, afford their complex and messy histories the same scrutiny.

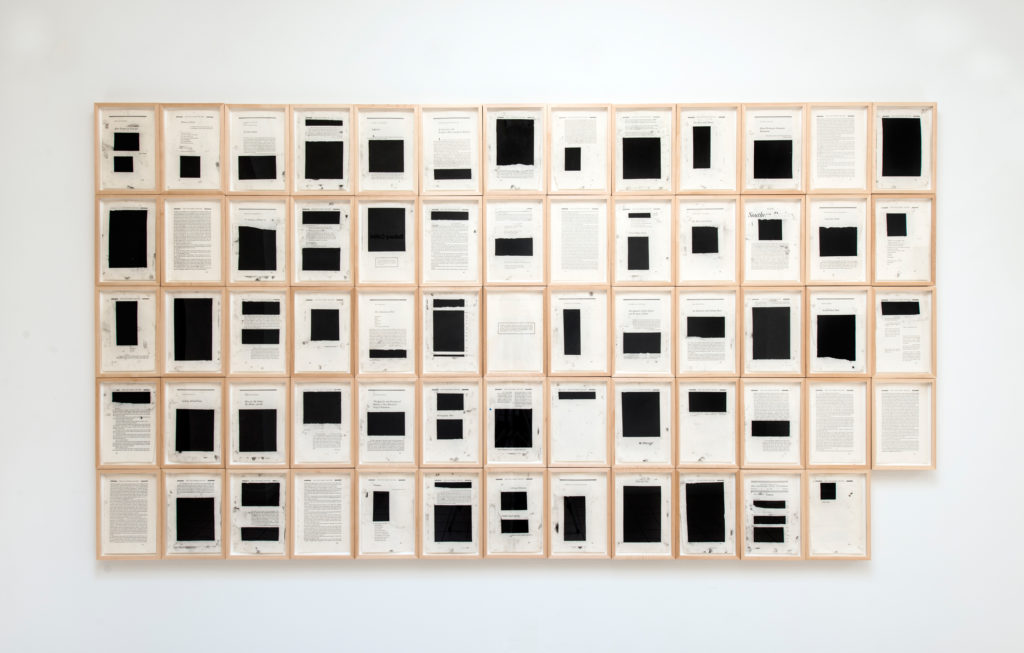

The messiness of history is the harbinger of abstraction. Whatever narratives do not fit the master plan are diminished, rewritten, or entirely lost, abstracted to the point of unrecognizability. Out of Easy Reach works to tackle, “the crisis of visibility of women of color within the narrative of abstraction’s history.”2 Bethany Collins’ on-the-nose Southern Review 1985 (Special Edition), literally omits wide swaths of text from the pages of the eponymous “Southern Review” with imposing black redaction marks. The artist has framed each page and hung them in a grid, reaping surprising formal relationships between disparate text blocks. Alternatively, Abigail DeVille’s, I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me,3 (2015) features shredded archival photographs from the Vivian G. Harsh Collection of Afro-American History and Literature Archive. Where Collins’ Southern Review is clinical in its presentation, DeVille’s I am invisible… embraces the haphazard appearance of collage. Situated in the last gallery near the conclusion of the exhibition, DeVille presents a flat, nexus-like assembly of mirrors, glass, photographs, epoxy, and CRT TVs. The work is disarrayed and sentimental, but hard-edged and incisive. Louder than Romany, DeVille’s work advocates for abstraction, but moreover advocates for messiness as a form of abstraction. Messiness is all-inclusive, cuts no corners, indexes everything yet, in its unorganized totality, is difficult for outsiders to crack. Only you know your mess best. Messiness as abstraction, as a method of simultaneously obscuring and archiving one’s own identity is a radically reparative act.

It’s no surprise, then, that the exhibition’s curation placed a notable number of works in gallery corners. Jennie C. Jones, Ayanah Moor, and Abigail DeVille’s contributions to the exhibition all spring from and skirt along corners. Steffani Jemison’s, Same Time creates its own corners, and Caroline Kent’s overwhelmingly reverential, First you look so strong, Then you fade away (2015) and Procession (2015) are the sole occupants of the exhibition’s smallest back gallery. Messes and their liberating indiscrimination grow out from the margins, disrupting the oppression of the scripted and orderly. They are encroachingly peripheral until they are not any more. As Out of Easy Reach’s exhibition statement asserts, abstraction holds the power to move “beyond binary thinking, beyond the body, and beyond the expectations of representation…”4 Perhaps, instead, the vector of messiness as abstraction moves the body, its representation, and binary trappings beyond us. They are accounted for and cataloged but left to mélange with the contradictory and textured— just beyond definitive grasp, and out of easy reach.

Out of Easy Reach was open at DPAM, UIC’s Gallery 400, and the Stony Island Arts Bank until August 5, and is now at the Grunwald Gallery at Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana.

- them. “How Gender Impacts Everyday Life | Sister, Cister.” Filmed October, 2017. Youtube video, 9:48. Posted October, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R9hbF13BqKE.

- “About,” DePaul Art Museum, UIC Gallery 400, and Stony Island Arts Bank, July 20, 2018, http://www.outofeasyreach.com/.

- “I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me from Nobody Knows My Name,” 2015

- “About,” DePaul Art Museum et al.