Proposals for an In/Exhaustible Image of Identity: Prisoner of Love // Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago

by Jameson Paige

It is challenging to describe an exhibition where the central artwork is so overwhelmingly exhilarating, present, and difficult. Yet, such is the predicament for viewers of Prisoner of Love at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) Chicago. Curated by Naomi Beckwith, the show sources its title from Glenn Ligon’s piece of the same name. The museum’s recent acquisition of Arthur Jafa’s acclaimed video piece, Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death (2016), acts as the impetus of the show. Though an enormous installation in scale and capacity, Jafa’s work is padded by an evolving constellation of artworks that explore the immensities of life and death, love and hate, pleasure and pain—themes pulled from Bruce Nauman’s well-known neon piece, Life, Death, Love, Hate, Pleasure, Pain (1983), also included within the exhibition. The three chapters of the exhibition move between these dualities, mobilizing a rotating cast of canonical artists, such as Carrie Mae Weems, Catherine Opie, and Doris Salcedo, among others.

Beckwith’s curatorial approach spatializes what Krista Thompson has termed the ‘sidelong glance’— “sidelong glances at Western art and cultures of vision…[are] a knowing way of looking that is very aware of, and in many regards averting, being seen in overdetermined ways on account of ‘color.’”1 As such, one of the permanent fixtures of the exhibition is the opening relationship between Nauman’s loud, central, and commercially-cognizant neon work, and Glenn Ligon’s shade-throwing, though much quieter painting installed to its right, entitled Untitled (Study #1 for Prisoner of Love) (1992). Through the proximity of these two works, the universalism embedded in Nauman’s understanding of the human condition is contested by Ligon’s racialized use of appropriated text “WE ARE THE INK THAT GIVES THE WHITE PAGE A MEANING,” which identifies a reading of blackness hidden in plain sight. This opening axis to the exhibition provokes a productive tension in subjectivity—questioning who is looking, who is feeling, and how these actions are linked.

For viewers, Jafa’s central artwork exists just beyond this first dialectic encounter. Similar to his other filmic works, Love Is The Message… amasses a series of found, disparate video clips, that convey an ontology of blackness for Jafa, many representing images of black people across time. The single-channel, 7:30 minute video samples materials ranging from university pep rallies, civil rights movement protests, Gospel music concerts, and Jafa’s own footage of theorists, such as Hortense Spillers. Rather than distill black life into a narrow search for survival, the sampled images’ final collaged form illustrates how “black subjects navigate the afterlife of slavery in moments that span the emotional register—from laughter to refusal to quiet contemplation.”2 In Love Is The Message…, Jafa focuses on images and sound to concentrate a combined affective ‘volume’ that is so dense it brings nightmare and ecstasy into close proximity—retaining a sublime incompressibility that somehow becomes singular.

The rhythm of Jafa’s syncopation of images within the film is guided by the soundtrack of Kanye West’s “Ultralight Beam”—a song that has been termed a gospel-infused “street parable.”3 Jafa has remarked on multiple occasions that in his work he aspires “to make a black cinema with ‘the power, beauty, and alienation of black music.’”4 Through Jafa’s manipulations of speed, tactful shearing, and incorporation of sound, the varied visual source material congeals into an evererupting pulse. The work becomes fragmented, incomplete, and narratively unstable—certainly embodying his aspirations for a black cinema.

restricted gift of Emerge. Courtesy of the artist and Rhona Hoffman Gallery.

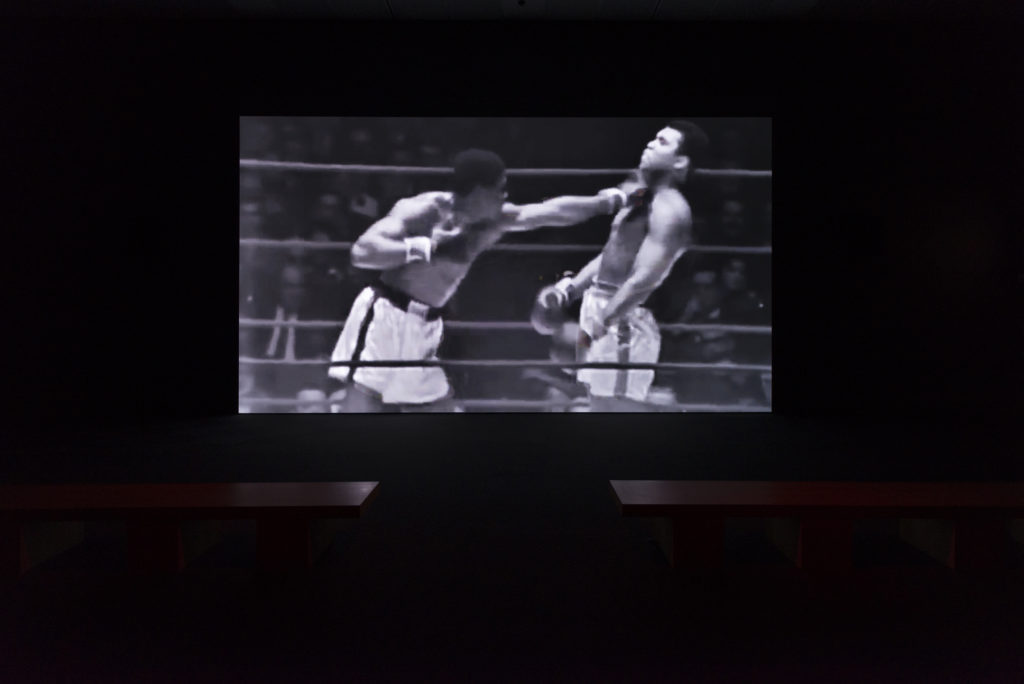

Part of the work’s ability to stir extreme affect—joy, horror, rage—is designed by its rhythmic hypnotism, which leaves viewers unable to resist complicity in Jafa’s peppered images of violence. It is this aspect that forms some of the video’s more haunting sequences. One example is a legendary vogue battle between the late Kassandra Ebony and Leiomy Maldonado (known as the “Wonder Woman of Vogue”) that curtly transitions via a death drop fake out into a woman being smacked across the room and knocked out. Maldonado’s slow motion, gravity-defying stunt recalls The Matrix (1999), inspiring exhilaration and joy in viewers—yet that joy quickly evaporates as the infamous death drop seamlessly folds into actual violence. Images continue to leap in content and affective measure—from the skilled scoring of an NFL touchdown, to Okwui Okpokwasili’s strained solo choreography—the melding of multiple cultural forms into a single complex schema. This unending compression snowballs into the single video work that is Love Is The Message…, focusing Jafa’s concept of blackness while sporadically likening its immensity to that of the glaring sun.

Art historian Huey Copeland connects Jafa’s work to black feminist artists before him, such as Renée Green and Lorna Simpson—artists who transgressively imagine how black bodies can be imaged in new configurations. Copeland posits that “Jafa’s works can be understood as forms of anti-portraiture that qualify the stilled representation of black figures in order to illuminate the dialectical relation between the self and the social.”5 This dialectic is woven as a constant spiral throughout Love Is The Message…, attuning viewers to one’s inability to control how the self is constructed by perceptions of race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, etc. at the societal level. Within this context, blackness is shaped by the complexity of these signifiers’ interlocution.

Whereas the act of becoming visible often provides the relief of representation, it subsequently binds a subject in expectation, calculability, and limitation. Jafa’s film adheres to this formulation, but pushes further, so that the images envisioning possibilities of blackness are inexhaustible. The cropped condition of these video clips reminds viewers that much has been left out, also pointing to the conceptual and material limits of visibility. Though Jafa’s work considers blackness’ confrontation with being seen, its fragmentary condition continuously evades seizure.

There is, however, an inevitable end to the video, signaling a death to the image that simultaneously represents and binds. The ending aptly depicts a collapsing James Brown during a 1964 performance of “Please, Please, Please.”6 The original version shows Brown being picked back up to his feet and cloaked in blanket, presumably to care for him, but more so to enforce his responsibility to perform. Jafa’s appropriation cuts earlier, where Brown is still on his knees pulling away from his impending and unwilling resurrection. The screen and music abruptly drown out as Brown exhaustingly screams.

Following Jafa’s complex piece, viewers encounter two surprisingly disappointing works by David Hammons and Lynda Benglis, which lazily appropriate Buddhist iconography and the Hindi language respectively. These pieces unfortunately undermine the complex embodiment of identity in Love Is The Message by perpetuating the shortsighted notion that Eastern spiritual practices can ‘heal’ the wounds the West has inflicted, illustrating a reductive Eastern essentialism in tow. The remainder of the “life and death” iteration of the exhibition expands upon Jafa’s emotionally raucous film into quieter territory. Melvin Edwards’s Off and Gone (1992) welds together volatile and aged metal fragments like chains and hooks to constrict a much more pristine water faucet. Here, the heaviness of history chokes life’s flow. Catherine Opie’s melancholic photograph of a demure, veiled, and empty armchair that floats before a blue drenched backdrop is utterly arresting when viewers note its title, In Memory/Leigh Bowery (2000). Anyone aware of Bowery’s exuberance for bright color, wild forms, and outlandish fashions will instantly become cognizant of the deep reaching feeling of loss registering on the body. The residual impression left on the empty chair longingly conjures the beautifully complex, warm fullness of Bowery’s persona, yet is unable materialize an image for us to grasp. Though much of this exhibition confronts the limits that images impose on us as human subjects, Opie’s work demonstrates that sometimes all we want is just one more photograph to hold onto.

As the exhibition cycles through its remaining two chapters—entitled “Love and Hate” and “Pleasure and Pain”—younger artists, such as Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Deana Lawson, and Michael Armitage bring further dimension to black figuration. The show’s central grounding of blackness causes a ripple through the imagistic strictures that configure identity’s appearance within the cultural field. However, one wonders if any image— singular, moving, abstract, or collaged—can match Jafa’s reflective use of the sun to depict the immense, astronomical feelings that one life can contain.

Prisoner of Love at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago ran through October 27, 2019.

- Thompson, Krista A. “A Sidelong Glance: The Practice of African Diaspora Art History in the United States.” Art Journal 70 (2011): 11.

- Copeland, Huey. “b.O.s. 1.3 / Love Is the Message, The Message Is Death.” ASAP/J. September 15, 2018. Accessed March 5, 2019.

- Kelly Price quoted in The FADER. Tanzer, Myles. “The True Story Of Kanye West’s “Ultralight Beam,” As Told By Fonzworth Bentley.” The FADER. April 04, 2018. Accessed March 05, 2019.

- Campt, Tina and Arthur Jafa. “Love Is the Message, The Plan Is Death,” e-flux Journal 81. April 2017. Accessed March 5, 2019.

- Ibid.

- James Brown. “James Brown Performs “Please Please Please” at the TAMI Show (Live).” Filmed October 1964. YouTube video, 6:16 minutes. Posted March 16, 2013. Accessed March 5, 2019.