Anne Collier: Open me like a book

by Ruslana Lichtzier

Anne Collier photographs reinvent the galleries of the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago as a sacred modernistic white cube, a frequently imagined space, but one rarely accomplished. Amidst the holiday cacophony and the David Bowie Is exhibition, Collier’s show is set apart in silence. At once enigmatic and revealed, it stimulates cool and yet intense seductions.

Collier is both a collector and a storyteller; her private, obsessive archive speaks to the history of the development of iconic images by their equally iconic producers. Both through photographing and re-appropriating images, she produces photographs of pictures that appear in books, records, folded posters, postcards, on top of stacks of photographs, at times in a development tray, or cut through a rotating cutter. The works always reveal a two-fold story—the image tells one, the title another.

The strategy that is employed is one of sequence. Collier creates multiple sequences within one photograph as well as between sets of photographs. An ebay-found, generic image, features a nude young woman, standing in the ocean, facing her back to the beach and to us; in 2007 Collier photographed and reprinted the found poster as a large-scale print, California Poster. A flat, generic portraiture of the California girl—maybe a kind of a self-portrait of the LA-born artist. This photograph instigates a second step. Negative (California), from 2013, is the reprint of the original negative—as a negative, after the artist found it online. In it, the ocean turns, as in reverse, to a surreal dune-like, threatening landscape, which an illuminated figure is going towards. In effect to this chain reaction, the first photograph, California Poster, cannot exist without the second.

Two photographs are presented next to each other on a wall.

Open Book #6 (George Platt Lynes) and Open Book #7 (Light Years) features two open books, held by the artist. The frontal composition, which shows the artist’s arms, but not her portrait, simulates and offers us the position of the artist. Again, an empty portrait. The open book becomes a photograph, and in return, the photograph suggests its reading as an open book. The two black pages of Open Book #6 (George Platt Lynes) read as modernistic factuality; echoing Malevich’s Black Square (1915), they represent the art historical chapter of “it is what it is.” But Collier doesn’t stop there; as often times, her exposed photograph conceals as much as it reveals. By naming the photographed book, George Platt Lynes, she not only clashes parallel histories that the modern trajectory ignored, but she also reveals her sources; those that combine crude modernistic origins together with pop culture in all its glam—as signified by George Platt Lynes himself, a luscious early twentieth century fashion photographer.

But maybe we can read into this even further. The photograph Open Book #6 (George Platt Lynes) dates to 2011, the same year that Lynes’ first book of male nudes was published. While throughout his lifetime, Lynes was known as a fashion and commercial photographer, his most passionate endeavor, photographing nude pictures of his male friends, remained concealed, in fear of the public’s reaction. It was known among his friends that on his deathbed Lynes destroyed his collection of negatives and prints. Only recently did it come to be public knowledge that he also sent a considerable amount of work to Alferd Kinsey, who at the time was researching homosexuality. In 2011, the year of Collier’s photograph, Lynes photographic work was published in a book by the Kinsey collection. With each photograph Collier narrates analogous and conflicted histories that are both general and deeply personal.

Of course, it is worth noting that this strategy—not the material manifestation—has appeared before in the works of Richard Prince, Sherrie Levine, Louise Lawler, and the grandfather of the Pictures Generation, Andy Warhol.

Two photographs are presented next to each other on a wall.

Trope, but yet affective seascapes, held in Kodak boxes, titled 8 x10 (Jim) and 8 x 10 (Lynda). Two stacks of what look like test prints, expose only the top two photographs, but reveal, trough the repeated prints, the unseen obsession that motivates a photographic act—to arrest the unique out of the stream of mundane. The titles again propose a second reading. Jim and Lydia are Collier’s departed parents; their ashes were scattered, twenty years apart, at the same location in the Pacific Ocean. Now, the photographs are read as evidences in an attempt to hold on to trauma; they present the congenital link between the photographic practice and the traumatic memory, both surrounded by an essence of a loss.

One should not, however, make the mistake in thinking that Collier’s photographs are tragically heavy, they are, in fact, rather light and humorous, a quality that saves them from being cool and ineffective; they can make you smile.

My Goals For One Year, from 2007, is a photograph of an open—probably self-help—workbook, pages number 13–14; which presents an empty fill-in list of personal and career categories. I imagine having this damn book in your studio. Siting in a corner of a desk, it calls to you, demands: write down your goals, for one day, another day, for a week, a month, for a year. So fucking depressing. As if to fight it, Collier photographs the pages. What seems to be an impotent battle, a battle that points to the inherent impotency of the photographer, exposed in a full-blown print of helplessness in front of the demand, and becomes, through humor, Collier’s weapon. It does present an unsolved problem of the call made by the Other.

Problems, from 2005, is a photograph of a cassette tape on a white backdrop. Silent, or rather mute, it manifests a photographic paradox, a medium that is trapped in absolute visuality. We read photography, but we cannot hear it. Like an outdated self-help recording, its voice is trapped in stillness; the photograph cannot teach us how to break through, and listen. This, is a problem. The silence, that listens to itself, is what you hear while walking through the exhibition.

In result, or rather in attempt to dive into the problem of the medium, Collier turns to the object of visuality—to what makes the visual possible, the eye. She develops her eye and her gaze in Developing Tray (2009), a black and white photograph of an enlargement of the photographer’s eye. The print is centered in a development tray floating on a black background. She cuts her sight and edits it in Cut (Color) (2009), where what seems to be a same size print of her own eye placed on a rotating cutter; her gaze is sliced in halves. In another photograph, Eye #1 (2014), Collier holds her eye, objectifying it into a print. In these works the artist positions herself as a female photographer in a world that is constructed by the male gaze. In return, her vision is sliced, by definition; in it, she can only edit, cut and objectify her own.

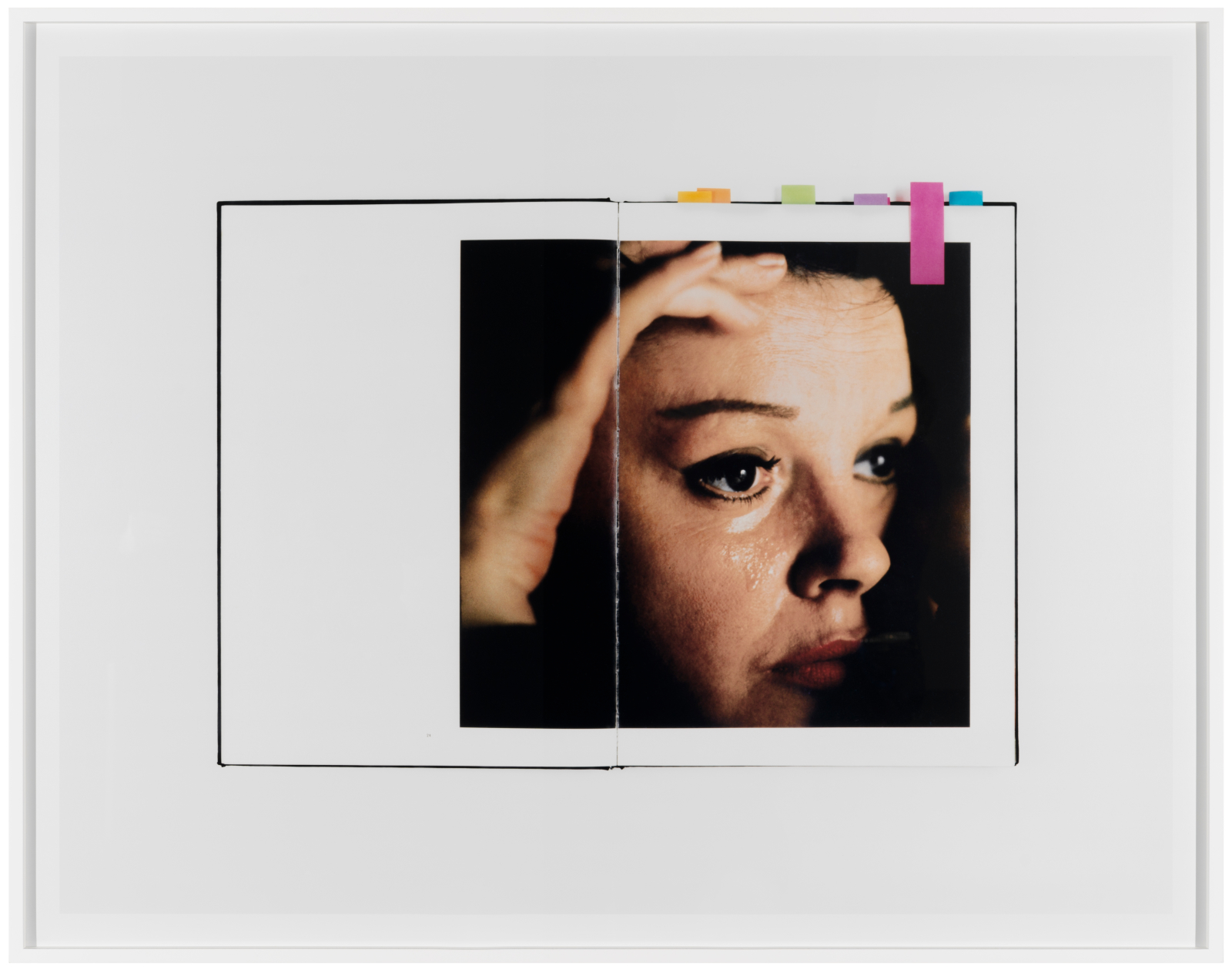

Her ongoing project since 2006, Woman With A Camera, gathers found images of female bodies next to cameras. What seems to be a self-empowerment strategy, in Woman With A Camera (diptych), that presents two reprinted promotional images of the 1978 movie Laura Mars, there Faye Dunaway points a 35 mm Nikon toward an unknown target, becomes much more puzzling statement in Woman With A Camera (The Last Sitting, Bert Stern) (2009). Here we see Stern’s open book, colorful page markers attached to it from all sides creating a colorful frame, and pointing to, yet again, other hidden photographs. The book is open to a picture of Marilyn Monroe, in her last photo session, 6 weeks before her death. Here she points, again, the 35 mm Nikon camera, this time, back to the photographer. Monroe remains unnamed, untitled, the notation refers to the photographer. Our gaze is trapped in her immortal, all encapsulating morbid glory, and I wonder, what kind of gaze we are forced to activate. Not only are we being put back in the male position, which activates the voyeurism, but also, the so-called empowered position of the female photographer is been given to the fetish object—to the model, and it takes a picture. The subject of this missing picture is the photographer. I do not feel that Collier writes a feminist manifesto that inverts female objectification, as others have claimed. Collier instead works through the complexities of the impossible seductions of the photographed female body, a seduction that is not spared from a woman photographer. She falls in love with it and laughs at her weakness. She slices her gaze because that’s the only thing she can do.

In this exhibition, we are confronted with very still photography. There is no one and nothing here to make a scene. There is no scene, no living bodies—only registrations.

Anne Collier is on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago through March 8, 2015.