Aphorism | Anthem: Sonic Avenues #3 // Christine Sun Kim

by Patrick J. Reed

You give up the world line by line. Some sentences touch a nerve, and some, like this one, excerpted from Cormac McCarthy’s play The Sunset Limited (2006), compress it with all their might.1 I recall books that nauseated me and passages that tickled me, but rare is the sentence that stopped me dead in my tracks. Stopped the day. Stopped the generator running in my heart that sustains the illusion I know where I am going and why.

I shelved McCarthy for a while because it had seemed, in the late 2000s, that any dude with a proclivity for the arts had persuaded himself that he was heir to the novelist’s moralizing vision of apocalypse achieved. To a degree, I played that game too. I conjured a world on fire and put it to paper. But the game was never gay enough, no matter how aggressively I mined All The Pretty Horses (1992)for homoerotic subtext; no matter how hard I tried to queer to the apocalypse. Even the end of the world belonged to the good old boys. Yet stumbling across The Sunset Limited at the Pasadena Public Library, I decided to return to the good old boy who brought us, for example, the story of a hitman who impales craniums with a captive bolt pistol, out of a curiosity as to whether his work still felt authoritative on the subject of evil. I thought a play, that literary structure long favored by queer writers, might offer an alternative glimpse into McCarthy’s basilic literary record. I glimpsed therein you give up the world line by line, a sentence spoken by a suicidal professor to the man who saved him from jumping in front of a train.

The plot that develops around these two characters, named “White” and “Black” to indicate their respective skin colors and their opposing values—White seeks to kill himself, Black strives to stop him—provided few takeaways besides the adage in question, which struck me as the tautest definition of creative practice. I think in terms of drawing, and I think in terms of writing; often I struggle to separate the two, despite the artist-critic dichotomy. Both practices isolate the maker, no surprise there, but I found these efforts set one on a course out to sea. Every graphite mark and every turn of phrase adds another notch to the distance between you and the shore you thought you knew. You on your ghost ship, your quarantined ocean liner. Or rather, me on the Diamond Princess of my mind, scanning the horizon for the green flash at sunset that will assure me the adventure was worth it.

In 1973, Agnes Martin, another mystical, desert-dwelling loner of American Modernism, though not one whose authority I have doubted, created a portfolio of 30 screenprints in gray ink on cream-colored paper entitled On A Clear Day.2 Most of the prints feature carefully constructed grids, but the sixth through the tenth prints feature horizontal lines separated by margins made wider as the sequence progresses. The tenth print holds the widest space within its eight divides, such that breath seems to pass through them. Perhaps for this reason it calls to mind, if one can abide a little ekphrasis, something lyrical and open—like an aeolian harp or a composer’s staff or the framework for a freedom song. I happened to be researching these prints during the period I was reading The Sunset Limited, and my understanding of them was transformed as a result. What seemed at first like a meditation on the unnamable qualities of existence, as expressed through Martin’s spare abstraction, became a decisive statement on boundaries. I saw lines drawn in the sand and options canceled. I saw Martin’s famously uncompromising principles—to live in isolation, to commune solely with her inspiration, to destroy any painting that failed to meet her inspiration’s standards—unveiled. I saw illustrated in those prints the world she gave up in order to draw the line of best fit for the life she wished to live.

A coincidence: my research on On a Clear Day and my reading of The Sunset Limited intersected in time with the 54th Super Bowl, which aired on the Fox Broadcasting Company channel starting at 6:30 pm Eastern time, Sunday, February 2, 2020. For most of my life, with a brief exception in 2014 that was precipitated by a desire to party by whatever means necessary, I avoided this program. I do not care about the NFL, but the 2020 edition caught my attention because a) I do care about Shakira’s halftime show ululation, and b) I do care about the inimitable CSK, that is Christine Sun Kim, the artist who performed the national anthem and “America the Beautiful” in American Sign Language during the pre-game ceremony.3

I met Kim, whom I will call Christine, a handful of times while I was living in Berlin, usually at a dinner of the sort where the menu is conceptual, the concept is water, and everyone’s taste buds get the night off. When I saw her on television that winter afternoon, sheathed in a shimmering ice-blue dress and cool as could be, I remembered her unflagging poise. It is a quality that comes through in every interview or presentation that requires her to explain her Korean heritage, her Deafness, her creative practice anew, anew, anew; to explain that sound is her medium of choice, that “sound is like money, power, control—social currency,” but also like a ghost: felt though not seen.4 And silence, by vernacular standards, is “a very obscure sound” because true silence is an impossibility for the hearing and the deaf alike.5

In a 2013 interview, conducted on the occasion of her visit to Ultima, Oslo’s Contemporary Music Festival, Christine elucidated the links between her past and the basis of her art. “When I grew up,” she said,

I knew your social rules related to sound, […] even though I couldn’t hear; I didn’t have access to the sound. For example, in a quiet place like someone’s home at 3:00 in the morning, I knew I couldn’t move around fast or tromp on the ground. I had to tiptoe quietly to make sure that people were still asleep. Or in a meeting, I knew it wasn’t appropriate to yell or move around so much that it would cause noise and disrupt the meeting. So I know your social rules really well, and that allows me to take ownership of the sounds.6

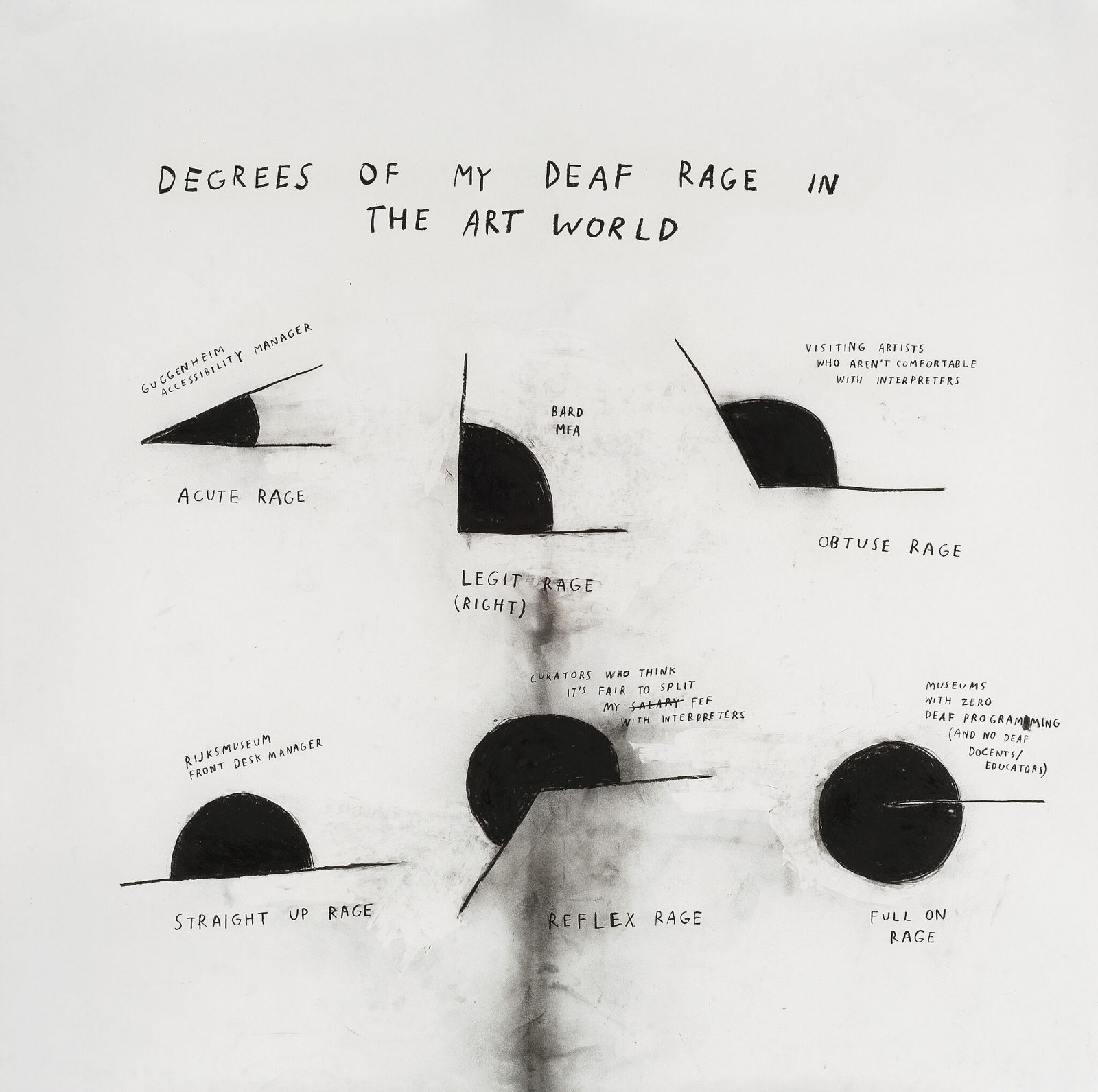

She navigates the hearing realm in ever evolving ways, which include performances that catalog the myriad variations of expression through movement, and deceptively spare installations that combine communication technology with visitor participation. Drawings are fundamental to her practice. The “Deaf Rage” pie-chart drawings schematize her astonishing encounters with a hearing-centric culture and document the extent to which society fails to apprehend Deafness. Degrees of Deaf Rage While Traveling (2018), for example, recounts “GETTING HIT IN THE HEAD WITH A BAG OF PEANUTS BY A FLIGHT ATTENDANT WHO TRIES TO GET OUR ATTENTION” at nearly three-quarters full rage, demonstrating once again that Christine is cooler than the average customer.

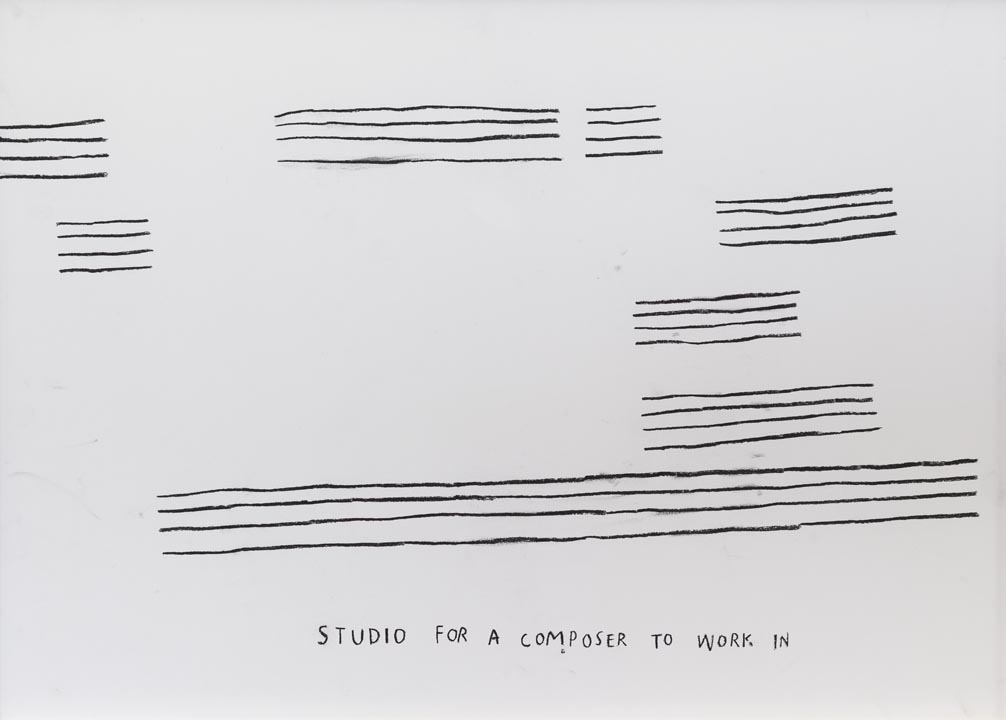

In the artist’s work Available Spaces for Composers (2016), her impulse to diagram, and thereby claim, sound alters the status of the musical staff from its rank as a substrate upon which music actualizes to an inherently “sounding” object. The drawings that comprise this eight-part series depict the staff broken into different configurations, each captioned with handwritten block letters that evoke the conventions for ASL glosses.7 “BATHROOM FOR A COMPOSER TO WORK IN” accompanies three long staff groups located atop six bite-sized clusters, while “KITCHEN FOR A COMPOSER TO WORK IN” accompanies five musical staff groups hard justified to the right. The staffs describe space in abstract terms made known to the viewer only through textual assistance, yet even if we accept at face value, these images in relation to their words—the meanings particular to their line quality and placement—remain elusive to us. Their lines are uneven, segmented, eye balled. Their charcoal pigments smear across the paper. Christine’s hand is very much present in these marks, made with the same hand by which she also speaks. Hence, we can, at least, understand the four lines that comprise her staff. As she explains in “The enchanting music of sign language,” her 2015 TED Talk, signing the word “staff” with four fingers instead of five, a count that refers to the traditional number of lines in the bass and treble clefs, feels more natural to her, and is thus an idiosyncrasy that is carried over into the drawings.8 Furthermore, “[…] there are no notes contained in the lines,” as she told her audience, “[…] because the lines already contain sound through the subtle smudges and smears.” They contain sounds of unmeasurable nuance. This is Christine at her most Fluxus, foregrounding the value in the structure by playing (with) the structure itself.

Christine’s performance at the Super Bowl was but another, grander instance of this subversive play. There she was, on the forty-yard line, among parallels that truss the American dream, giving new shape through locomotion to an ethos too long unformed. Such grace. Wisdom in motion. Seeing her there, all my thoughts hove into alignment. On a Clear Day. You give up the world line by line, and you remake it with your own two hands.

Sonic Avenues is an ongoing column by Staff Writer Patrick J. Reed that features essays on contemporary artists engaging with sound and the larger cultural implications of their work.

- Cormac McCarthy, The Sunset Limited. (New York: Vintage International, 2006), 131.

- Cormac McCarthy has been affiliated with the science research center, the Santa Fe Institute, as either a fellow or a trustee since the 1980s.

- For more on Shakira at the Super Bowl LIV, see “Sonic Avenues #2: Ululation,” also published in THE SEEN online; www.theseenjournal.org. To see Christine Sun Kim’s Super Bowl LIV performance of “America the Beautiful” and the national anthem, see the following videos posted online by the National Association of the Deaf (NAD): “Christine Sun Kim Performs ‘America, The Beautiful’ / Super Bowl LIV,” YouTube video, 2:12, from a performance televised by Fox Sports on February 2, 2020, posted by “NADvlogs,” February 3, 2020, www.youtube.com/watch?v=EmXFzQo4BFw&feature=youtu.be; and “Christine Sun Kim Performs the National Anthem / Super Bowl LIV,” YouTube video, 1:58, from a performance televised by Fox Sports on February 2, 2020, posted by “NADvlogs,” February 3, 2020, www.youtube.com/watch?v=c2TCT5HYlHQ. These videos are necessary documents provided by the NAD, as Fox Sports failed to broadcast Christine’s performance in full, an egregious error that caused a furor on social media, especially among the Deaf community.

- Christine Sun Kim, “The enchanting music of sign language,” (TED Talk lecture), digital video, 15:09, from a TED Fellows Retreat, posted by TED Conferences LLC, August 2015; Siri and Sive, “Christine Sun Kim Interview,” (sirisivefilm) digital video, 4:52, Interview with Artist Christine Sun Kim during her visit to the Ultima Festival, Oslo, in collaboration with nyMusikk and Dans for Voksne, 2013.

- Christine Sun Kim, “The enchanting music of sign language,” (TED Talk lecture).

- Siri and Sive, “Christine Sun Kim Interview,” Ultima Festival, Oslo. For clarity, minor punctuation and style adjustments have been applied to quotations from this interview, which were taken from video subtitle transcriptions since the author does not speak ASL. The original words and their meaning remain the same.

- Per the Chicago Manual of Style, “[ASL] glosses are words from the spoken language written in small capital letters.” Chicago Manual of Style, 16th ed., 11.147.

- The sign for “staff” in ASL is made by passing one’s right hand, with palm facing inward, fingers extended in parallel, and thumb up, across the space in front of one’s chest, from left to right.