On Apology: The Uncertainty of Saying Sorry in Contemporary Art

by Paul Smith

In the late months of 2015, a proliferation of apologies in the form of popular music was introduced into the public sphere. This pop ‘key’ was not only a defining form of post-confessional pleading, but also an audible phenomenon—the sound of Justin Bieber’s “Sorry” and Adele’s “Hello” (both released October 23, 2015) colonized popular sound. Though the singles are aesthetically different (Bieber’s tone a mining of club hits, while Adele’s references the “blue-eyed soul” of the 1960s), both narrative arcs trace familiar gestures of contrition, using the brevity of the pop song format, paired with one-word titles, to plead with the object of their love; to consider a future (together). Like most apologies, these lyrics predicted a world to which only the apology gives us access—the things left unsaid, and everything that could be imagined thereafter. By contrast, Drake’s July 31 release (its music video appearing on October 4) “Hotline Bling” and, more presciently, Selena Gomez’s “Same Old Love” (released September 10) refused—and devastatingly refuted—any regretful explanations. As both Drake and Gomez apprehended the apology in utero, Adele and Bieber thus begged doubly.

The apology is used primarily for what is known. It follows the confession, which is the first half of absolution. The confessional speaker admits all faults, from physical activities, to motive and psychological formation. Even today, ‘confession’ in courts of law often extends past physical activities, seeking to reveal the intentions behind crime1. Apology, by contrast, is the anxious extension of an offer. The apologizer gets to stop confessing and proceed with a changed life; the receiver of the admission takes the apology as an indication that the offenses will cease, and perhaps, that a token is offered.2

The aesthetics of confession have been with us since Augustine’s “Confessions,”3 written between 397–400 AD, and stretches through eighteenth-century criminal literature, addiction memoirs, and twentieth-century confessional poetry. Michel Foucault’s 1981 lecture Wrong-Doing, Truth-Telling: The Function of Avowal in Justice, at the Catholic University of Louvain, traces the Western histories and discourses surrounding confession—from pre-modern practices of self-interrogation, through the development of contemporary judicial systems.4 Foucault argues that not only was there a “massive growth of avowal” in the modern era, but that what was first imposed as a religious and punitive demand became highly desirable: we know ourselves because we speak of ourselves, in “a discourse of truth that the subject is led to maintain about himself.”5

The sharpness of 2015’s trend in pop-y, publicly hosted apologies might indicate that, for the time being, apology looks, tastes, and feels better than confession alone. But if dramatic tropes tell us anything, few things are more delicious than a spurned begging. The myriad ways in which pop idols have apologized—and the increased attention on “non-apologies” in pop/public discourse—gestures toward a longer history that explores the challenge of saying what is more than speech: the non-verbal ‘sorry’s of art.

Art and apology start early. Ancient Olympic athletes who were caught would fund the erection of a statue of Zeus—the monuments were called Zanes.6 These public tributes performed contrition and restitution simultaneously: with the cheating athlete’s name inscribed on the base, the figures continually attested to the cheater’s disgrace, while also honoring the public (and god). The offender must, as it were, hold up the public on their back (on the base), to atone for their sins. Likewise, Carravagio’s David con testa di Golia (1610) is often cited as apologetic: here, Goliath’s head is Caravaggio’s own who, then on the run for murder, allegedly gifted the painting imaging the artist’s clemency to the Cardinal Borghese. But both of these works were created before the modern concept of apologies took hold. Ancients sinned not against each other but against order, and the devious athlete or artist made amends to a public or exterior power than anchored social hierarchies. In this sense, Caravaggio apologized not to a grieving family, but to the official who could absolve him; disgraced Olympians made amends with god.

Interpersonal forgiveness was not developed until the early, albeit wildly hypocritical, infancy of egalitarianism in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.7 Modern apologies exist as a reconstitution of equal grounds for individuals—not the reconstruction of an ahistorical hierarchy (as performed by the earlier examples). In this modern context, the offender is the subject who upsets the very grounds of social relations, inhabiting a false higher ground—one they do not deserve. From this history, forgiveness depends on the coeval idea of the malleable, flexible self it implies or expects—that we can change and change for the receiver of our sorry’s.

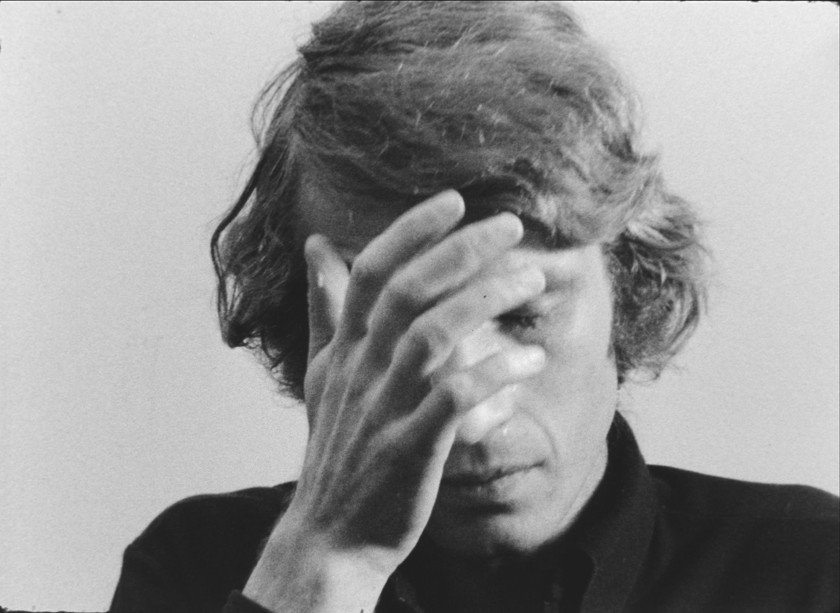

Nearly three centuries after Caravaggio, we find that the role of the apology in art has much more complex tenets. In Bas Jan Ader’s 1970-71 film I’m Too Sad to Tell You, we find the artist crying—out of remorse or grief, we are not sure—for three long minutes. While Ader’s sadness is tacit, the work does not ask us to assume he is apologetic. Instead, the elements of public flagellation, vulnerability, and insistent affects spread (one might say impose themselves) onto the viewer, suggesting that Ader’s weeping compensates for a wrong that has happened elsewhere. Observing this sort of intimacy feels like an aggression, but whether on Ader or the viewer’s part is uncertain. I’m Too Sad to Tell You compels us to find justification, to apologize for the viewer’s forced intrusion onto the artist—and, then uncomfortable at the scene, expect Ader to apologize to us. The film illustrates the ambivalence central to a good apology: witnessing or receiving a sorry that is not meant for the viewer vacillates between the seductive, the abject, the insulting, and the embarrassing. The grounds keep shifting.

Belated and excessive apologies are insincere, and evince a concern more for the sender than the receiver, as though the apologizer could absolve their own crimes through vocalization. Not all confessions are cathartic—and not all catharsis is the right choice. The apologetic subject upraises themselves through flagellation. Some artists have made a living with this kind of apology. In 1995, Peter Santino released his first “apology.” The text, entitled I AM SORRY, reads in part: “It has become clear that what I must offer is my sincere apology…I am sorry for allowing my ego to convince me of my cleverness/I am sorry for allowing that cleverness to permeate my work/I am very, very sorry.”8

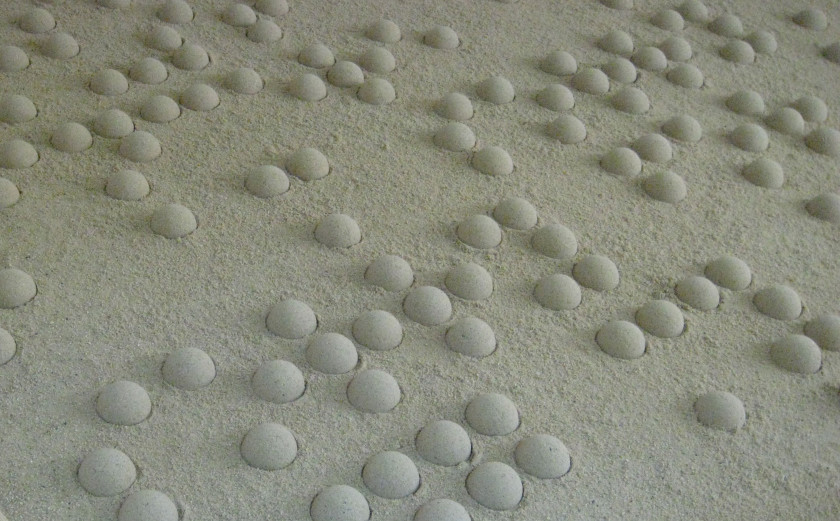

Santino’s apology is reasonable for an artist in the throes of doubt. Who hasn’t wanted to apologize and disown their creations? But following the proclamation, came a career of repetitions: the 1995 exhibition of 1000 cement balls arranged to read, in braille, “I am sorry, I am very sorry” at the Watari Um Museum in Tokyo in the fiftieth anniversary of the U.S. bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki; the original apology text rendered in raised sand in 1996; “je suis désole” in 1997. The sharpest iteration comes in 2009 in Leipzig, where Santino rewrote I AM SORRY in braille with hemispheres of sand. To read the apology is to destroy it. As Santino suggests, perhaps apologies need be erased or fade to take hold, though their performance is contingent on concrete change over time. This progression is absent from Santino’s career—as such, the irrelevance of the apology, when portrayed as a linear narrative, becomes increasingly apparent in the work as time proceeds (and Santino keeps on apologizing).

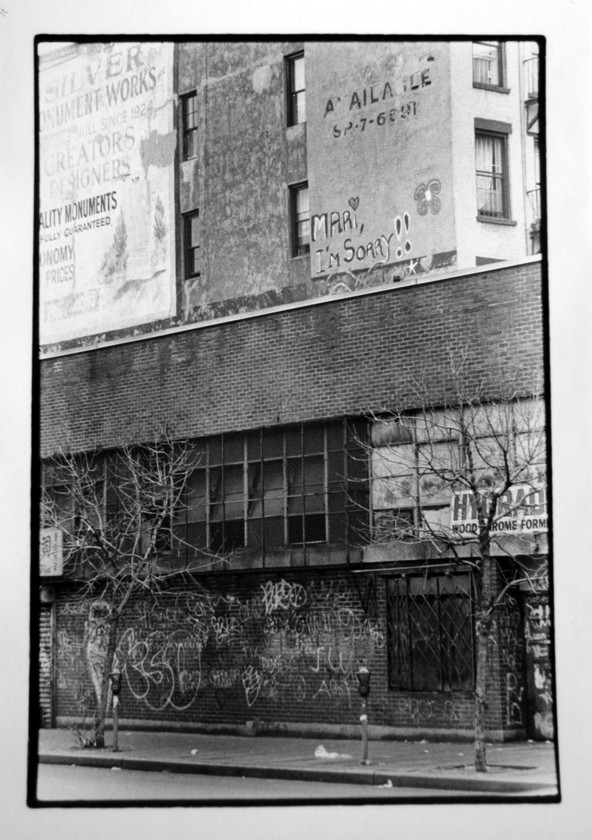

In a 1995/97 silver gelatin print, Zoe Leonard documents a spray-painted apology on the high side of a building, beneath and beside the old painted signs from deceased businesses advertising space and service. The text and the title read MARI, I’M SORRY!!, the first “I” dotted with a heart. Is this application of paint, like its companions on the walls, an advertisement of wares? Or is it splayed at random? Adorned with a flower, the text is a sharp rejoinder to the scrawled graffiti on the streets below or the block letter “AVAILABLE” wearing thin above. The saccharine imagery is testament to painful (to behold, at least) honesty, just as viewers land the distasteful role of observing a privacy they would perhaps rather not.

As with Ader, this public display of sincerity is disconcerting. In his text/lecture “Sublime Humility,” Paul Chan observes a careful distinction between humility and humiliation—while both are a humbling, only the latter gets us stuck.9 Humility—a sort of brave sincerity—unlocks the future of the apology for contemporary art. Here, one is humbled, but commits to concrete change. Though I’m Too Sad to Tell You was shot multiple takes, there is little doubt that Ader is sincere in his work (the piece is hard to read as ironic or distanced). Santino’s works might point to some confessional tendencies, or the frustrating politesse of compulsive apologizers. Just as Bieber’s riskless apology can afford to be upbeat, Adele’s is contrasted with an implied heartbreak. In both art and music, only the latter seeks to bare words as more than their weight.

To be functional, apologies must carry weight. The Latin root of gesture is gestus—‘to carry.’ So apologies must carry, transmit, and be heavy, or risk being the empty gesture that has no properties of holding. In “Sorry,” Justin Bieber asks “is it too late?” Too late is an apology that cannot carry, just as his ex Gomez makes clear by saying “I’ve heard it all before at least a million times” (almost five thousand times more than Bieber’s “by once or twice I mean maybe a couple of hundred times”). “Hotline Bling” and “Same Old Love” call out the non-specificity of their received apologies in advance—a pre-denial. What makes Bieber’s “Sorry” an empty apology is his refusal to take full responsibility for his actions. Bieber already voided his check—Santino, too, cashes in without full-measured sincerity. The unlikelihood of I AM SORRY being sincere is that its excess is more about clearance than change. No one enjoys this excess.

Apology is not only the content of multiple works of art, it is also a strategy. In his 2003 essay “Claiming Contingent Space,” Liam Gillick argues that “one of the important roles of a curator in a dynamic context now is to pre-apologize for something; to try and set the scene and to qualify expectations, and to make sure that there is no excess of expectations.”10 The “pre-apology” facilitates what Gillick identifies as a larger project of dispersal: rather than curators, critics, and artists producing sweeping gestures with concrete agendas, they instead multiply the ramifications of any given object. The “pre-apology” is also a function of extensive programming, as Fionn Meade observes: “if you frame out and schedule time for critical discourse, you’ve already met the ‘discursive’ expectation, a pre-apology.”11 In this light, apology can be seen as a series of qualifications, retractions, and tentative marks. Critique can be preemptively shut down by acknowledging failures—inviting the enemy to the camp, in a sort of gesture that says “yes but—”

Riskless apology is tendered towards removing obstacles, thus ensuring a more seamless transmission of the object, idea, or artist themselves. Is apology still ‘sorry’ if it’s an excuse, a pre-apology or partial retraction that allows the artist to save face without trial? Saying sorry in advance allows the rest of the statement to proceed unhindered—it is the qualifying mark, not the whole apparatus. Apology is admission in both senses—price for the future and burden of responsibility for the past. Both Drake and Adele make clear the stoppage their statements effect on them—similarly, Ader and Leonard document (one closely, the other at a distance) apologies that are largely public pauses. They take effect through the massive baring of affect, unlike those other cases that don’t try hard to feign feeling.

To be effective, the apology must be local. This poses an inhibitive context for art, which is so materially and conceptually specific, but perhaps less so for popular music, which caters to a larger scale public and has different strategies of facilitating projection. One cannot apologize to the [whole] world. This is why we read Leonard’s document as sincere, imagining it in the narrative of a story, and why Santino’s work elicits fatigue. Apologies are tenuous and small. This apprehension of locality appears only in the modern apology. When used today, it is the pre-modern “sorry’s” generality that obviates true contrition and responsibility.

The popularity of apologies, then, plays to two sides: the first smuggles sincerity into the public eye, while the other expresses a tacit desire for the continuity of acting a certain way. What of the receiver? To refuse the apology is to block the apologizer by condemning them to the eternal return of their crime. In this way, forgiveness as a means to an end is no purer than directed apology.

Using apology as content (Bieber and Santino)—as opposed to method (Ader, Gillick and Adele)—circumvents sincerity. As Bieber states in an October 2015 interview, “[‘Sorry’] is kind of the stamp in the end of the apologies that I’m giving to people. Why did Bieber replace the usual idiom—“seal”—with “stamp”? Perhaps, when stamped, his apologies can be seen as a postcard from a byegone Bieber, a federally issued means of transit or ticket to a better tomorrow. In another impression of “stamp,” Bieber conflates apology with a final gestural mark. A stamp is designed to move words across locales. The tastiest apologies are anxious, unsure of their rights to travel, unconvinced of their ability to carry. The sincerity of apology is equal parts naiveté and retraction.

Using apology as a method—as Bieber and Santino’s work make clear—circumvents sincerity. As Bieber states in his interview statement, “[‘Sorry’] is kind of the stamp in the end of the apologies that I’m giving to people”12. If we interpret ‘stamp’ for ‘seal,’ then apologies can be seen as a postcard, a federally issued means of transit or ticket to a better tomorrow. In another impression of the term ‘stamp’ (to stamp is to impress), Bieber conflates apology with a final gestural mark. A stamp is designed to allow for a parcel or letter to move across locales. The tastiest apologies are anxious, unsure of their rights to travel, unconvinced of their ability to carry, if the sun will rise again. The sincerity of apology is equal parts naiveté and retraction. As artists such as Ader and Leonard make clear, the honest apology is an uncertain one.

Paul Smith is a critic and curator, currently based in Chicago. He is co-director of Cornerstore Gallery, assistant in the Hans Ulrich Obrist Archive, and Bookstore Manager at Kavi Gupta Gallery. Paul contributes to Newcity Art and The Seen. His work deals with commodity cultures in art history.

- In The Culture of Confession from Augustine to Foucault, Chloe Taylor defines the confession as “understood not simply as relating to the circumstantial acts or arbitrary thoughts of the speaking subject, but much more significantly as being the truth of her inner subject,” which is produced “through this form of discourse” (Taylor, 80).

- Ibid.

- Augustine

- Foucault, Michel. Wrong-Doing, Truth-Telling: The Function of Avowal in Justice. Trans. Sawyer, Stephen W. Ed. Fabienne Brion and Bernard E. Harcourt. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2014. 18.

- Ibid.

- http://odysseus.culture.gr/h/2/eh251.jsp?obj_id=5824; http://www.contemporaryartgallery.ca/blog/cheaters-cheating/

- Konstan, David. Before Forgiveness: The Origins of a Moral Idea. New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Accessed at: http://www.santino.tv/archive/Failure%20Institute/sorry.htm

- Chan, Paul. “Sublime Humility.” Paul Chan: Selected Writings 2000-2014. Basel, New York: Laurenz Foundation, Shaulager, and Badlands Unlimited, 2014. 44.

- Gillick, Liam. “Claiming Contingent Space.” Curating with Light Luggage: Reflections, Discussions and Revisions. Liam Gillick, Maria Lind Eds. Berlin, Munich: Revolver/Kunstverein München, 2003. 134.

- Meade, Fionn. “Spaces of Critical Exchange,” Interview with Liam Gillick. Mousse 33.

- Justin Bieber in conversation with Kent (Smallzy) Small, on the Australian radio show “Smallzy’s Surgery,” October 2015. https://soundcloud.com/smallzyofficial/justin-bieber-at-the-mtv-emas-2015-smallzys-surgery