Art of the Lived Experiment: UICA

by Alexandra Kadlec

Novelist Paul Auster once remarked, “Changing your mind is probably one of the most beautiful things people can do.”

The promise inhabiting this statement can be read as the driving force behind Art of the Lived Experiment (ALE), the international, multi-venue exhibition arriving in Grand Rapids this month. Featuring visual and performance art by twenty-six disability artists from all over the world, ALE’s call to action for visitors is to come with an openness to explore, engage and, quite possibly—leave transformed.

ALE premiered at DaDaFest International 2014, a Liverpool-based festival with the aim of celebrating difference and fostering meaningful discourse through deaf and disability arts. Originally curated by Aaron Williamson, the exhibition focused on the everyday, inevitable processes of change and adaptation in our lives, including our impermanent minds and bodies.

The inaugural and only U.S. appearance of ALE opened April 10 at the Urban Institute for Contemporary Arts (UICA), the Fed Galleries at Kendall College of Art and Design, and the Grand Rapids Art Museum. For this iteration, co-curated by Aaron Williamson and Amanda Cachia, artists have been similarly invited to interpret the concept of life as an experiment: one full of curiosity, risk and unpredictability.

The responses, provocative and kaleidoscopic in both context and content, in turn invite viewers to experiment with their meanings. Two works illuminate one of the many thematic angles present in the exhibition: the complex matter of identity—or, to be more specific, obscured identities.

In London-based artist David Lock’s portraiture series, Misfits, 2013, a collagist approach has been undertaken in an attempt to divide and disrupt the subject. The title implies the desire to fit, while acknowledging this impossibility for some.

But there is another possibility here: to examine the pieces individually and resist broad categorization of the whole. “In a sense,” says Lock, “harmony can never be achieved, as each fragment plays a part of a lost totality. This sense of loss underlines the vulnerability, but also strength and character, of the portraits.”

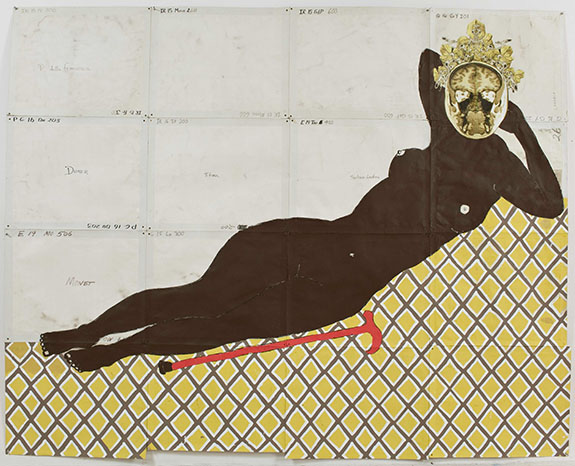

California-based artist Katherine Sherwood has abstracted representation further in Maya, 2014, appropriating Manet’s Olympia, 1863, but disguising the face completely with the image of a brain scan and a halo made up of historical neuro-anatomy images. A cane rests by her leg, adding another element of questioning into the picture.

The use of Olympia “was significant in many respects,” says Sherwood, “including her bold frontal gaze that was unseen in previous odalisque representations.”

The deliberation of this work is further asserted by biographical undertones. Having suffered a massive cerebral hemorrhage in 1997, Sherwood often uses scans of her own brain in her work, introducing new and unexpected forms of beauty—albeit a foreign, somewhat haunting kind—where the viewer least expects to find them. Displayed next to another variation, Sherwood’s Olympia, 2014, at UICA, these dual representations become imposing figures that challenge the viewer, their confrontational poses making it impossible to look away.

The human face represents what we might come to know, or not know, about someone. In the act of looking at another, we observe, investigate and infer in the blink of an eye. We read facial expressions and make judgments of attractiveness, intelligence, personality. When access to this is denied, or distorted, we are compelled to stop and think differently, and perhaps to look elsewhere, to make sense of things. The same could be said when prejudices or preconceptions cloud our vision, when we are not willing to see beyond our own experiences.

In myriad ways, the art and artists of ALE challenge this resistance by raising a number of questions worth considering, both individually and collectively. How do we identify disability: mental, physical, emotional, economic or otherwise? How do our abilities and disabilities enable or inhibit us from navigating the world, including our interactions with others? How might the creative act become a vehicle for reshaping our perceptions of difference? And then, what do we do with this newfound knowledge? By stepping into these conversations, our capacity to change and be changed begins to expand.

Art of the Lived Experiment, currently on view at UICA, the Fed Galleries at Kendall College of Art and Design, and the Grand Rapids Art Museum, runs through July 31, 2015.