Barbara Kasten: Stages

by Joshua Michael Demaree

Photographer Barbara Kasten’s work is like a jolt of electricity to the eye. Her signature pieces that feature the fragmentation of form coupled with a studied use of color is instantly striking, capturing the eye’s attention even thirty years after their creation. But it is her craftsmanship, her powerful control of the work’s materiality, that truly holds the viewer’s attention—revealing the sagacity of Kasten’s on-going exploration of the interplay between mediums, specifically sculpture, installation, painting, and photography.

The first major survey of Kasten’s work opened at the University of Pennsylvania’s renowned Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) in Philadelphia on February 4 and will run through August 16. The exhibition presents a selection of her work from across nearly five decades, as well as the debut of a newly commissioned piece, Axis (2015), paired with ephemera surrounding Kasten’s work in both fine art and commercial contexts, and her role as an activist for women photographers.

That this is Kasten’s first major survey is shocking. While her influence is clear, especially during the Digital Age, her recognition has been minimal despite her place as a dexterous link between 20th century art movements and the 21st century. When surrounded by her work, it becomes instantly clear that Kasten has been heavily influenced by Russian Constructivism and Bauhaus design. In fact, while attending California College of Arts and Crafts, Kasten studied with Trude Guermonprez, herself a second-generation students at the Bauhaus, working in textiles. Kasten’s early work reveals Guermonprez’s influence (whose masterfully weaved textiles transcend into forms and representation previously dominated by sculpture and painting) openly through her use of textile in sculptural works and her Photogenic Painting series of cyanotypes.

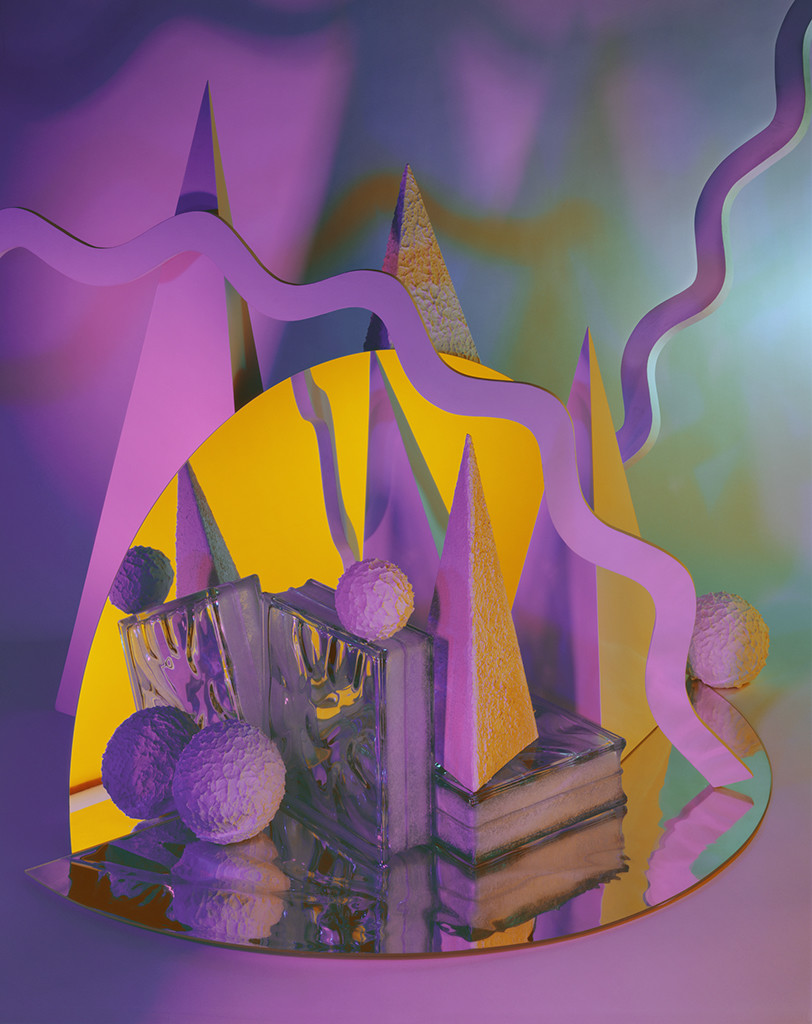

Despite these historical references, Kasten keeps an eye ever-forward. The aesthetics and form of her most famous work from the 1980’s, her series of Constructions, capture a distinctly modern visuality. Each construction entails a sculptural installation (Kasten calls them “props”), the arrangement of meticulous lighting, which she then photographed with polaroid film. From her cyanotypes to these constructions, we see Kasten’s fascination with the interplay of three-dimensional spaces translated into two-dimensions, how documenting a space not only flattens it, but confuses it. This confusion is doubly so, since Kasten uses her props (sculptures, glass, and mirrors) and her lighting to fracture the planes of the space, ensuring that the complexities of her three-dimensional constructions are doubled when one dimension is removed.

While Kasten uses this seemingly basic exercise in form as the basis for many of her subsequent series for the next two decades, her aesthetics in doing so have remained prescient of visual cultural tastes. Her architectural site series, in which she moved her constructions to a grand scale by using newly constructed architectural spaces as the set for her variety of mirrors and props and lighting, presents a series of images that evoke the digital age that would come to take unfaltering prominence in less than a decade’s time.

Digital visuality favors the easily fragmented and manipulated. High contrast has, in the past decade, switched to a preference for over-saturation, which has been a characteristic of Kasten’s lighting for the past thirty years. The power in her images are that they once presented a well-crafted foreignness, but now can be found in copies of form and color in hundreds of thousands of Instagram feeds.

Her work, though an inspiration to present day digitally-altered images, does not, however, share in the same infinite reproducibility of those images. In many ways, her work counteracts the idea of the cheap image—that an aesthetic eye and moderate technical skill in Photoshop can create a thing of lasting beauty and fortitude. While these images are demanding of attention, they are essentially without cost or value. Kasten’s work is meticulous and it shows and this, more likely than her foreshadowing taste, is the lasting power of her work.

In a video shown on the ICA’s second floor, we watch as Kasten and her assistants orchestrate Architectural Site 17, August 29, 1988 at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, Georgia. The event is grueling. Working all night, her and her group arrange and re-arrange props and lighting equipment. Then they sit and wait. She takes photograph after photograph as the light shifts throughout the night. Soon people have arrived for work, but eager to capture how the soft morning light will interact with the site, she has an assistant block the doors. The video illustrates Kasten in masterful control of her art—a kind of control that requires technical skill, determination, and a magisterial attention to detail.

Beyond the impressiveness of Kasten’s prescient eye or her commitment to the quality of her craft, is her devotion to nearly five decades of study to one essential idea: the interplay between three-dimensional and two-dimensional space. This fidelity to creative research is of a bygone era. Art culture—now largely inseparable from digital culture—for many overindebted MFA graduates demands constant reinvention. A personal kind of one-upmanship fostered by a wrongfully enshrined sense of neoliberal individualism.

This is why the show’s newest work, a video titled Axis (2015) that was commissioned for the exhibition, feels cheapened in comparison to her other work. It is a logical step for her studies in light and form over the past decade, but loses the materiality that so endears her earlier work. In a show amassed with concentrated studies of a singular concept through gradually transitioning mediums, the leap to video is a shock. It suffers from its singularity. With this being said, Kasten’s mastery of moving from three to two-dimensions is enough to keep me attentive to any futures attempts she makes in video.

The ICA, which has made a name for itself by coupling exhibitions of new talents with established (and often under-appreciated) powerhouse artists for shows that run for months. The runtime is kept fresh by a focus on amazing programming, bringing in artists and curators to comment on the exhibition, giving it new breath every few weeks (not to mention their frequent celebrity visitors, including both Questlove and Dev Hynes in recent memory). Barbara Kasten: Stages is no different with upcoming discussions with art-designers Peter Shire and Martino Gamper as well as Kasten herself alongside David Hartt, Takeshi Murata, and Sara VanDerBeek.

Barbara Kasten: Stages, curated by Alex Klein, is on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia through August 16, 2015.