Basim Magdy: The Stars Were Aligned for a Century of New Beginnings

by Omar Kholeif

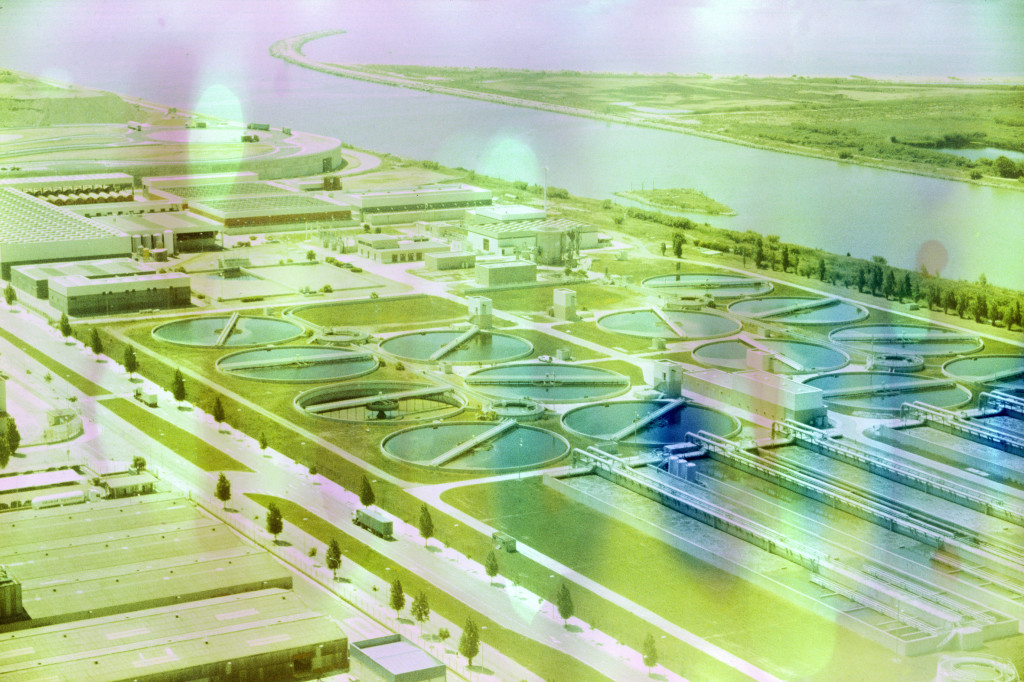

Basim Magdy was born in Assiut, Egypt, and now lives and works between Basel, Switzerland and Cairo, Egypt. Magdy’s work introduces viewers to the world through a satirical eye—his drawings, sculptures, videos, and installations are conceived with a taste for the absurd. Like dreams, elements of a familiar landscape stem out of reality where past, present, and future exist within a single realm of depiction. Within his practice, images—often depicting foliage and ruins, astronauts and rockets, airplanes, soldiers, cranes, and modernist structures—take on an aggressively surreal quality. Magdy’s references, from the slick veneer of advertising and sinister tropes of science fiction, to the televised style of nature and science documentaries, adopt an array of classical and unconventional media, including chemically altered film stock, a term the artist has coined ‘film pickling.’ Magdy spoke with Omar Kholeif, Manilow Senior Curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, on how his painting process has impacted the production of his films, his self-taught photographic practice, and the role of humor in his work.

Omar Kholeif: You studied as a painter in Egypt before you moved to Europe. I am curious how important is the practice of painting to you? Who were the figures that inspired you? And can you tell me more about them?

Basim Magdy: Painting is something I have enjoyed immensely for as long as I can remember. There is something about making creative decisions every second for hours at a time that I find gratifying. For the past sixteen years, painting and creating works on paper have been an essential part of my practice, running parallel to anything else I did—be it a film, a photography project, or an installation. Although, I am a slow painter, it is still the fastest way for me to capture ideas. The logic behind the layering process I use when I paint, which could mix as many mediums as acrylic, gouache, oil, spray paint and collage elements together, is the base for how I layer images, text and sound in my films. The framing of images in my films and photographs is always influenced by the way I compose my paintings. I guess I could say that the one painter whose work I have been consistently fascinated by since I was fourteen is Joan Miró. During the early years of my development as a person, my father—an artist and a writer himself—introduced me to his art book collection, which became a valuable source of inspiration to me. It was one of the main reasons why I decided at that early age to become an artist.

OK: Many of your early works on paper and canvas evoke a pop cultural sensibility: what was the inspiration for your early subjects and how did you construct them into works—was there a narrative floating between them?

BM: This was an experimental phase. I was trying to figure out what I was really interested in; it was a time to try different things. I guess part of what you describe as a ‘pop culture sensibility’ has to do with my fondness of bright colors and simple forms at that time. I was working a lot with stills from war movies. Later on this somehow evolved into an interest in more complex issues like the different visions of the future that never materialized, (i.e. where are the flying cars?) or a logic that proposes absurdity as a communication tool.

OK: Over time, you taught yourself how to use film and photographic technologies: what moved you in this direction?

BM: It started with my first encounter with a Super 8 camera, which was probably around 2008. Growing up in Egypt meant that, unlike in the US and Europe, owning a Super 8 camera to document holiday memories was not a common thing. This made that first encounter more of a discovery than a reason for nostalgia. I immediately became fascinated by how film does not attempt to mimic reality in its finest details. It has its own color and quality. It has its own interpretation of reality. Another thing I love about film is its tangibility as a material which allows me to see my fingerprints on it and change the image by introducing elements to its surface, may that be punching holes in it, drawing on or scratching it or even dunking the film in the most unexpected of household chemicals to see how the film emulsion reacts to this exposure it wasn’t designed for. Later on I moved on to working mainly with Super 16mm film but I also started exploring photography from a similar angle. I didn’t know much about film or photography when I started, but I consider myself lucky that it happened at the time of Youtube tutorials, because that is how I learned everything I know about shooting film and operating all the cameras I own. I found myself in this awkward situation, where I was obviously using what most other people would think of as an outdated medium, but was insisting on educating myself through Youtube tutorials because I believed printed manuals were outdated.

OK: You have devised this term ‘film pickling’: tell me what this formal process means conceptually for the work?

BM: I think of what I do with moving and still image as fiction. Exploring different ways to alter a photographic representation of reality is one of the tools I use to construct fictional narratives. I personally become more receptive to believing fiction when it visually defies my expectations. It started with an online post by a film enthusiast who put a roll of film in the dishwasher and posted scans of the outcome. I was fascinated by how the ordeal altered the film’s colors beautifully. I started using different chemicals and initiating my own process. What I also like about the process, apart from the painterly colors and the partial unexpectedness, is its flexibility to respond to different conceptual frameworks. I have processed images this way in works that deal with the blurred lines between hopefulness and failure, recording possible post-apocalyptic landscapes, or to construct the setting for a complex failing love story. Somehow the colors are always capable of making reality look otherworldly—while the photographed subjects sustain the familiarity of what we see around us.

OK: Your subjects: in any media always seem to be confronting the future, negotiating whether they are living in a world of utopia, or post-apocalyptic science fiction failure. Where has this perspective emerged from?

BM: I guess it has something to do with my very early interest in both surrealism and the theater of the absurd, but it really mostly evolves from my own observations of the world around me and how I, like most people, am constantly trying to analyze things for a better understanding of the world. When I was in my 20s, it felt as if the 20s were going to last forever, but suddenly you realize you’re in you’re 30s and that’s when the future and the passing of time become pressing daily thoughts. It is also the time when my personal experiences allowed me to mature in different ways, and I realized that there were no utopias—so I started seeing the world from that perspective.

One of the rewards of making fiction is that you can let your imagination run wild. My films are often embedded with subtle political observations, investigations of how societies function, and the active or passive roles individuals play within them. There is also the constant fluctuation of how images, text, and sound describe one another in what I hope is a poetic way. All of this is showcased inside endless questioning of what it means to be alive, in the sense that being alive is a process of going through time with all of its events, accomplishments, failures, and aspirations.

OK: Where do you think technologies are taking us?

BM: It is very hard to tell, but I hope it will take us towards a balanced mix of hopefulness and failure. I am confident, though, that we are heading for a future with much bigger gaps between the mega rich, the rich, and the poor. I believe this also applies to countries as much as individuals. We are already at a time where generating technology is a form of wealth and progress. I myself fall for the trap of reducing an answer to this question to how we will communicate in the future, and what the future holds for art—both of which are somehow related—but I think things will be a lot more challenging than how we communicate, and whether or not art will be collected twenty years from now, as the generation that casually shares millions of intricately composed images, videos, and writings for free on a daily basis comes of age. Technology will continue to serve the industry of creating debt for people and nations alike, just as it will continue to produce more capable weapons to fuel that debt. At the same time, it will continue to look for exit routes in our oceans, outer space and finding cures to incurable diseases. The future is a tangled web of billions of unexpected events. It will be an algorithm gone wild, and there is no way to anticipate what could happen.

OK: You often deploy humor as a technique through titles and sub-titles—do you have any specific comedic interests or references?

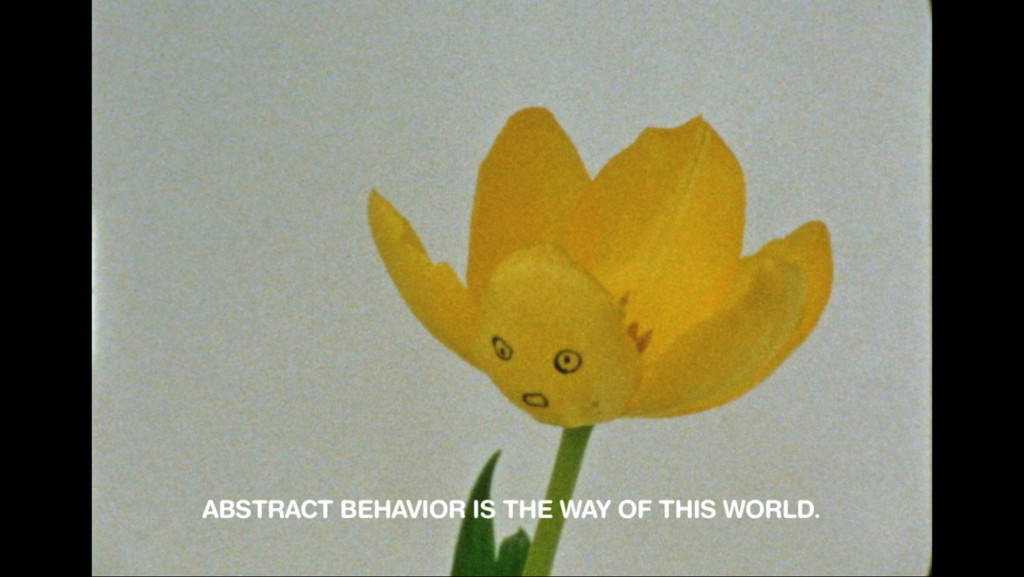

BM: Not particularly—I watch South Park, The Simpsons, Family Guy and Bob’s Burgers like a lot of people, but I do not know how much that influences my use of humor. My real interest in humor comes from a growing obsession with creating works that instigate an emotional reaction. I believe we all have the same feelings regardless of the languages we speak, our backgrounds or life experiences. We may express our feelings differently, but we all tend to laugh when we hear or see something funny. I like to use humor when I feel the subjects I am dealing with are too heavy, to balance things out. This started in my film 13 Essential Rules for Understanding the World (2011), which I see as a defeatist film, but also extremely realistic. I like to observe how people respond to it, which usually starts with laughs and smiles with the appearance of tulips with faces drawn on their petals and their seemingly narrating the 13 rules. By the 6th rule, people start realizing what is really happening there and the smiles are gone. No one wants to be confronted with the problems of the world without even a little bit of sarcasm or a smile.

OK: This is the first survey show of your work in the U.S.—what does it mean to look at all this work together and to consider in the same breath?

BM: It is an amazing feeling. The U.S. is the country where I have shown the most since I started working as an artist, and the number of shows I have had here exceeds any other country by a huge margin. So to finally have a solo museum show of this scale in the US and particularly at the MCA is really a milestone for me. It is also kind of emotional because of a personal story. On my first trip to the US in 1998, I passed though Chicago for 5 hours. I chose to spend 3 of them at the MCA—I was still an art student then, but I distinctly remember dreaming about showing at the MCA one day. It is finally happening.

The Stars Were Aligned for a Century of New Beginnings curated by Omar Kholeif will be on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago from December 10, 2016–March 19, 2017.