Beyond Buildings: Chicago Architecture Biennial

by Kate Pollasch

As it embarks on its second international forum, the Chicago Architecture Biennial opens this fall. Led by Co-Artistic Directors Sharon Johnston and Mark Lee, of the Los Angeles-based firm Johnston Marklee, the Biennial boasts a citywide exhibition and programing engagement plan that brings the proverbial architecture world to the Chicago stage. The theme of this year’s biennial, Make New History, unpacks the field’s relationship to its own history with a “me, looking at you, looking at me” self-reflexivity. Framed around questions of politics, power, and history, the Biennial poses the challenge: “how might we build connections to the past that are relevant and valuable to our present?” In the expansive complexity of this theme, architecture, design, documentation, and conceptual thinking stand on the same platform of importance, presenting an opportunity to examine the symbiotic ecosystem of architectural history alongside the often-myopic norm that positions the act of building as a prioritization.

Artists have a strong presence in this year’s Biennial, with many individuals operating under hybridized professions—that of artist, designer, architect, and educator—as the new norm of creative professionalism. Of the Biennial’s one hundred and forty-one practitioners looking closely at the relationship between art and architecture, the work of Ania Jaworska, James Welling, and Amanda Williams addresses strikingly different content within a similar conceptual language. Their works offer a new way of looking at the past, and a thought-provoking interruption of the present. In their own way, each artist calls forth what can go unseen to the everyday eye, reminding us not only of the flaws of human perception, but also the power in questioning how we consider the image of architecture. Each reflects a different understanding about architecture beyond the building, and beyond space, as a malleable platform for change.

In many ways, Chicago-based Amanda Williams sets the stage to the Biennial with her exhibition Chicago Works: Amanda Williams at the Museum of Contemporary Art, a satellite partner to the Biennial programing. Originally trained as an architect, Williams’ Color(ed) Theory (2014–present) project debuted at the first Chicago Architecture Biennial—the series, which included locating abandoned homes in the Englewood neighborhood set to be demolished by the city, featured their exterior monochromatically painted in electric colors, as if marking a declarative outcry on behalf of the buildings’ impending demise. The selected palette of the houses, devised from Williams’ own system, are associated with consumer products—the hues bearing titles such as Harold’s Chicken Shack Red, Currency Exchange Yellow, Safe Passage yellow, Newport Squares Teal, Crown Royal Purple, or Flamin’ Hot Orange, among others.

Throughout the Chicago Works exhibition, Williams builds upon this project, incorporating new sculptural and installations to set a stage that addresses how the forces behind construction, abandonment, revitalization, and demolition—the architecture of a city itself—equally shapes how people are affected by its influence. In speaking about this body of work, Williams mentions that the process opened questions about what it means to single out a community of which she was not resident—to be an outsider entering a community, and working with the insiders. Just as her practice inverses value and memory, Williams is also quick to challenge what community means.

In works such as Goldmine/is the Gold Mine? (2016–17), Williams inverses perceptions of material value and preservation by gilding a stack of bricks from a demolished house, and placing them in the museum’s context. The work begs the question: if what was once rubble is now coated in gold and given space to be studied, does its value change? Williams’ artworks refuses easy answers to these challenges, favoring instead the opportunity for more complex inquiry: who chooses value, what is the value of a brick on the streets of Englewood versus its placement within institutional walls? While the buildings and materials Williams works with are not invisible without intervention, her practice operates as a re-illumination on how passive gestures of neglect and disconnect can puncture and penetrate a neighborhood, just as strongly as active gestures of bulldozing, rezoning, and condemnation.

the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago.

With Williams standing at the front of the Biennial program, the fall opening at the Chicago Cultural Center anticipates more artistic considerations on what it means to interrupt pre-existing relationships to architecture.

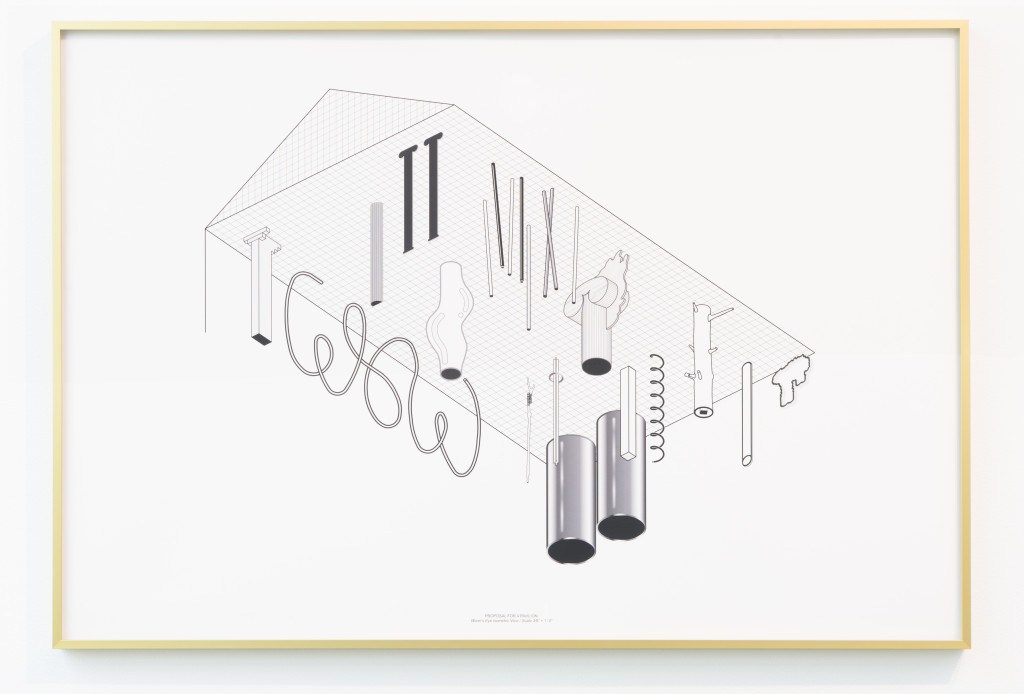

In the forthcoming installation at the Chicago Cultural Center, the work of Ania Jaworska and James Welling similarly imprints the building’s structure. Jaworska—an artist, architect, and educator—takes seemingly simple domestic forms and flips their context. In her sculptures and forms, such as bookshelves or stools, their central elements draw a phenomenological realignment, employing a subtle humor that rattles the viewer from their ‘bad posture’ and complicit relationship with objects and space. Jaworska’s work tackles one of the first forms of engagement and connection inside the Biennial’s central building that most would hardly notice—the concierge desk at the Randolph Street Lobby entrance. A structure for viewing and being viewed, Jaworska interrogates the form of the desk, which often silently communicates to visitors to approach and engage with staff, while also signaling that they are being monitored. Using iconic forms, such as the arch and the column, Jaworska’s intervention magnifies the entrance, at the same time it places boundaries and complications around its configuration. Elevating the desk and chairs so that seated staff and standing guests will interact at eye level, the installation recalls how Williams’ gold leaf bricks intervene with discarded architectural materials. By enveloping the old desk within this new sculptural skin, Jaworska does not destroy or dismantle its purpose, but rather re-visualizes how architecture can mediate information, engagement, and viewership in a public space. Welling’s work will have one of the least subtle locations in the Biennial exhibition—invited to photograph Mies van der Rohe’s iconic IIT campus and Lake Shore Drive apartments in Chicago, his photographs are installed on the façade of the Cultural Center in large scale. Through a deep artistic history with architecture, Welling has dedicated much of his career to photographing spaces and structures with visual curiosity and formal ingenuity. Tackling many of the titans of architecture, Welling’s photographs collapse time to create a visual space of unfamiliarity. In this recent body of work, as throughout his practice, Welling’s photographs render areas of artificial color with psychedelic electricity that counter the streamline, neutral palette of Miesian design to push even the most veteran architecture buff to wonder if they have been there before.

The Cultural Center—designed to speak as a marker of the city’s intellectual and metropolitan advances—and has been a longstanding beacon of free public engagement and programing. Layering images of the modern IIT campus and Lake Shore Drive private apartment within the framework of the public space, Welling collapses an additional layer of architectural thinking.

The concept of this collapse remains prevalent in contemporary practice. Welling interrogates what a building can mean at conception, creation, throughout history, and in the present day. In this timeless mobility, we return to Williams, and how her work in Englewood might translate forty years from now. As Make New History provokes, we must ask: will this biennial ripple outward as a source of applied change? Or will our new state of awareness leave us mired and unable to fabricate solutions and steps towards change?