Brick by Brick: Per Kirkeby // Kunsthalle Krems

by Ezara Spangl

The exhibition of Per Kirkeby’s works, currently on view at Kunsthalle Krems, appears to function as a sort of diminutive retrospective. The artist’s drawings and paintings are emphasized alongside his multifaceted practice—yet, what can be seen as one of the leading works within the show is a supplementary installation in the garden at the Minorite Church (Minoritenkirche), in nearby Krems-Stein. The brick sculpture, Untitled (1993), was commissioned by the Kunsthalle as a permanent outdoor sculpture as part of Zur Zeit, an exhibition of open-air sculptures in 1993. Alongside the majority of the works on view within the exhibition—which includes Masonite boards, drawings, bronze pieces, and canvas paintings—Kirkeby’s brick sculpture brings lucidity to the underlying logic of his practice within the context of this present show, which exists between abstraction and representation.

The solo exhibition was originally conceived for the artist’s eightieth birthday, but Kirkeby passed away on May 9, 2018 in Copenhagen, marking the exhibition unexpectedly posthumous. This shift in part transformed the exhibition into a concentrated look of his formation, impact, and legacy. Looking toward other artists’ work, Kirkeby was naturally influenced by minimalist artists, such as Donald Judd and Carl Andre, but also Kazimir Malevich, and his abstraction of the square. Kirkeby researched history and was interested in the Danish canon, such as neoclassical artist Nicolai Abraham Abildgaard, the Biedermeier master landscape painter Christen Schiellerup Købke, and sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen, who was working in Italy in the nineteenth-century, largely seen as the successor to Italian neoclassical sculptor Antonio Canova. Among these influences, Kirkeby wrote about Paul Cézanne, Édouard Manet, and Vincent van Gogh. During the 1970s, he was introduced to Michael Werner and became part of the Cologne art scene alongside Jörg Immendorf, Markus Lüpertz, and A.R. Penck. At that time, there was much prejudice against Germans in Denmark; as a Danish artist, Kirkeby was an outlier— actively showing in Germany and participating in the market there.1

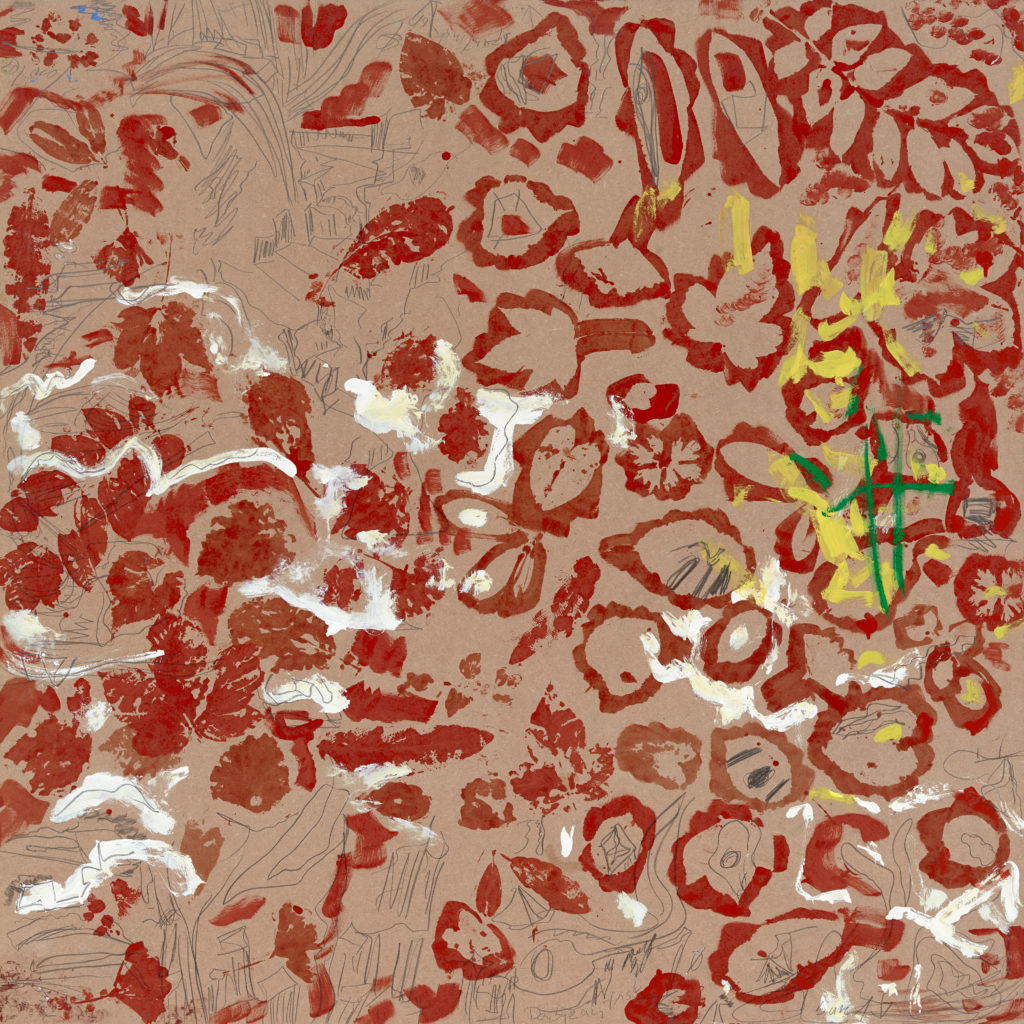

The earliest piece in the exhibition is the oil on Masonite work entitled Chac’erne mister orienteringen på grund af det gronne, den nye hovedfarve (1970/71). In this painting, animal and plant forms are visible in a field of green applied by many small brush strokes engaging positive and negative space. Kirkeby continued working for over forty years on square Masonite boards always in the same scale, roughly 48 x 48 inches. This format is shared with the blackboard pieces, in which he first used black paint to make a dark ground field for chalk renderings—as well as pencil, enamel paint, and spray paint, among other materials—for incessant portrayals of the natural world, declared as engaging the “Nordic expressionistic landscape tradition.”2

Throughout Kirkeby’s work is the expression of the hand the purveyor of ideas. Participating in the European tradition of oil on canvas, he was known for painting large wet-brush strokes of impasto paint, often scrapping off layers of paint and then building up new ones through this same process. Among these works included in the exhibition are also the Masonite boards, which repeatedly engage line to depict the natural world; drawings on brown or white paper using ink, chalk, graphite, and pencil through both line and rubbings; etchings; bronze sculptures cast from clay and plaster forms manipulated by fingers and hands; and the overpaintings, a series of painted-over canvases Kirkeby picked up in junkshops— as the artist states, “… I never painted over any picture I believed to have any kind of ‘value’ in the artistic sense. They were almost always pictures on the verge of being trashed.”3

Additionally, Kirkeby worked with language through the publication of his poems and essays, as well as worked in experimental film and theater scenography—including being commissioned by Lars von Trier for the films Breaking the Waves (1996), Dancer in the Dark (2000), and Antichrist (2009).4

The Naturens blyant (Nature’s Pencil) publication of essays from 1978 includes Kirkeby’s writings on his own practice, aesthetics, and architecture. In this publication—which is one of dozens of his books—he writes of historical influences: Francis Picabia, Öyvind Fahlstöhm, Bertel Thorvaldsen, Caspar David Friedrich, and J.M.W. Turner. In the frequently cited chapter, “En arkitekturhistorie (A History of Architecture),” Kirkeby describes his own architectural model as ‘neo-Gothic,’ ‘Classicist,’ and ‘neo-Baroque.’5 One review of the book articulates the prodigious nature of Kirkeby’s oeuvre:

…Per Kirkeby is not the first painter who expects the house to double as a picture. The house is a classic motif in visual art, and the painted picture once formed part of the house. What does it mean that the house itself is a picture? Kirkeby addresses the issue philosophically, abstractly, and actually. He refers to artists such as Ledoux, Ruskin, Pugin, and Morris, people regarded by posterity as driving the radical shifts in the development of architecture. Kirkeby shares elements of kinship with these people. He argues his case well: architecture as not merely anchored in systems, but to be reckoned with as works of art. Architecture that, by virtue of form, color, and decoration, melts into the imagery of whence we evoke a profusion of experiences…The text has much to offer architects. Per Kirkeby expresses himself succinctly. Not necessarily in overtly accessible and clear terms. But he manages to instill measures of uncertainty in readers with architectural backgrounds.6

In his paintings, Kirkeby frequently confronts viewers with expressionism bordering on mannerism. Combined with his multi-layered practice, it all comes across a bit like that of a heroic artist—however, this is not entirely true considering Kirkeby’s brick sculptures, which manifest his inspirations of the geological and natural world, are about the viewer’s perspective and engagement of the work.

Bricks are modular. They are assembled and laid. In his brick sculptures, Kirkeby locates a system that concurrently realizes his experience of space and light, while also creating form and support to his organic view. In the brick sculptures, the artist makes use of volume and hallow space— just as the use of the negative and positive space of the picture plane is realized in a completely sensorial manner. Coming into contact with the brick sculptures, some of which can be physically entered, the visitor may be guided by the sequence of walls, doors, and curves by entrances and exits, by volume and mass.

Born in 1939 in Copenhagen during the beginning of WWII, Kirkeby was surrounded by public housing buildings made of brick in the Bispebjerg district. One such large structure in his immediate childhood surrounding was the Grundtvig Church, which was finished just after his birth. It is a massive and dominant structure, at once implicitly somber and exhorting rigor. Kirkeby spoke of the influence of its architecture:

Yes, that was Grundtvig church. It is gradual, but also in hindsight it has become a good metaphor, not only for the possibility as far as the use of bricks. I was surrounded by this material since I was a child because there was no other building material. The time back then was before the spread of concrete; there was only brick. But this church had another meaning, because it was an unmodern, anachronistic building. It was only completed in World War II. But at first, it looks as if it comes from the Middle Ages. I do not think that is good either, because it is not right with the Middle Ages, it gets a little bit weird. I do not know for sure, but sometimes I think that this building imprinted on me.7

Before completing a degree in geology and paleontology in 1964 at the University of Copenhagen, Kirkeby joined the Experimental School of Art in Copenhagen. One of the artist’s earliest solo shows was in 1965 in Copenhagen with only four works—two of which were brick sculptures, stacked without mortar. Thereafter, bricks were always present in Kirkeby’s work. Later, after travelling to Mexico in 1971 and visiting Mayan ruins, he built his first functionless building in brick; the first brick sculpture that can be physically entered is the Huset (1973) in Ikast, Denmark. It is the size of a small children’s playhouse, composed entirely of bricks. He went on to design and realize many commissioned public and private outdoor works throughout Europe—particularly in Denmark, Germany, Switzerland, Austria, France, Spain, Norway, the Netherlands, and Belgium.

Important brick sculptures are far too numerous to list here, but a concise selection of works to contextualize Untitled (1993) in Krems-Stein: the house he designed on the island of Laesö (1994/95) as a vacation home for Dorte Mette Jensen and Arne Fremmich; the sculptures on Kirkeby’s property also on Laesö: Laesö I – XV (undated, but all after 1984); the Stubbeköbing (1975), which was first built as a chimney to smoke fish on the property of a friend in Grönsund, Denmark, though it was relocated to Sönderborg, Denmark; the works Karlsruhe-Universität I – VI, (1990); Ballerup I, II, III, Ballerup, Denmark (1996); and Grenoble I, II, III (1991/92) France.

The sunlight and space within the sculptures, at least of those that can be entered, are Kirkeby’s intentional secondary experiences. As Lars Morell writes, “Since 1988, Per Kirkeby has also begun to create brick sculptures that are enclosed and secretive on the outside but can be entered. In the inside of the sculptures, there are traces of sunlight which streams in through niches.”8 The works almost develop an equation: interior is to exterior, as room is to wall. The nonfunctional architecture provides space for the metaphysical; order and unity, calm and stability. The large sculpture at the Gothenburg harbor, Vindarnas Tempel (1992) can be seen far out at sea like a distant red spot, but also walked around and through from up close.

Within the body of the brick sculptures, there are multiple categories: unrealized, permanent, temporary, and architectural. Temporary sculptures such as those made in 2017 for Per Kirkeby: Brick Sculpture at the Palais des Beaux- Arts, Paris are executed with the expectation of being de-installed and stored. Other works such as Brick Sculpture (1994) outside of the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Humlebæk, Denmark are built as permanent commissioned works. There was also the occasion that a work was destroyed: work completed in 1982 in Kassel for Documenta 7 was, unfortunately, destroyed four years later. The only brick sculpture as of yet to be realized in the United States was at The Carnegie Museum of Art for the Carnegie International in 1995—this work was inspired by traditional pueblo architecture, built on an outdoor staircase and later disassembled.

Within his practice, fragments structure new forms: a door, a column. Kirkeby’s brick sculptures had their departure in architecture, yet remain primarily detached from function except to make metaphysical space. In his drawings, Kirkeby links canvas to cathedrals and arches to columns. He drew, studied, and photographed architecture, looking at Danish Gothic and Romanesque churches, such as the Haderslev Cathedral in Denmark. Kirkeby’s architectural observations into the views of gables, stairs, rounded arches, and colonnades and has been attributed to his 1960s Pop interests.9

It is a singular paradox that part of Kirkeby’s practice fits into minimalism, while simultaneously remaining idiosyncratic. As the artist states,

The brick sculptures also contain spatial considerations—about life and death, so to speak. That’s it, what makes the fascination of the successful brick works. By “brick” I mean in principal every beautiful material with which you can really make something beautiful. But there are limited construction options when one sticks only to brick, but actually, there are many ways open. Brick buildings, at least those that I consider to be successful, awaken a feeling that is hard to define when entering. What should such a handling of space and proportion, where one has nothing to gain, if one tries to describe the phenomenon formally. For me, the secret of these buildings had nothing to do with thoughts of life and death. Why are we here on this earth and how long, and what does death mean and what does it mean to say that death is perhaps the door to eternity?10

Of experiencing Kirkeby’s brick sculpture, curator Jill Silverman van Coenegrachts rightly articulates: “We are mystified, attracted, put-off, confused, inspired, and occasionally dismissive of their massive power and animation.”11 Viewing Kirkeby’s work is complicated; The ideal situation is such as that in Krems where the paintings are on view alongside to the brick sculpture—even if not precisely on the same premises—which in Krems and Krems-Stein accordingly requires zigzagging though the town to see both.

Per Kirkeby at the Kunsthalle Krems in Austria ran from November 25, 2018 until February 10, 2019.

- Kirkeby, Per. “Overpaintings,” in Kirkeby, Writings on Art, ed. Asger Schnack, trans. Martin Aitken (Putnam, Conn., 2012), n.p. (e-book), quoted in Steininger, Florian and al. Per Kirkeby, Kunsthalle Krems, (Vienna: Verlag für moderne Kunst, 2018), 33.

- Springfeldt, Björn. “An enourmous, textural universe.” Per Kirkeby: Paintings, Sculpures, Drawings, Books, Films: 1964—1990. Moderna museet, Stockholm, 1990, p.131.

- Kirkeby, 66.

- Ng, D. “Artist Per Kirkeby discusses painting, critics and ‘Antichrist’,” Culture Monster, Los Angeles Times. 23. Oct. 2009.

- Kirkeby, Per, and Ane Hejlskov Larsen. Per Kirkeby: Paintings 1957—1977. König, 2017, p. 233.

- S., “’Maleren og arkitekten’ (The painter and the architect),” Arkitekten, no. 10 (1978): 239, quoted in Kirkeby, Per, and Ane Hejlskov Larsen. Per Kirkeby: Paintings 1957—1977. König, 2017, pp. 233-234.

- Kirkeby, Per. “Per Kirkeby Im Gespräch Mit Siegfried Gohr.” Per Kirkeby Im Gespräch Mit Siegfried Gohr, by Per Kirkeby and Siegfried Gohr. Translated by Ezara Spangl. Kiepenheuer & Witsch, 1994, pp. 51–52.

- Morell, Lars. “Per Kirkeby’s brick sculptures,” Per Kirkeby: Paintings, Sculptures, Drawings, Books, Films: 1964—1990, Moderna museet, 1990 p.157.

- Kirkeby (n 6).

- Kirkeby (n. 10) 48-49. 11 van Coenegrachts, Jill Silverman. “The World is Material.” Kirkeby, Per. Per Kirkeby – Brick Sculptures, by Per Kirkeby et al., Cahiers D’Art, 2017, p. 61.

- van Coenegrachts, Jill Silverman. “The World is Material.” Kirkeby, Per. Per Kirkeby – Brick Sculptures, by Per Kirkeby et al., Cahiers D’Art, 2017, p. 61.