Charles Ray: Sculpture, 1997–2014 // The Art Institute of Chicago

by Terry R. Myers

No artist of his generation takes up space like Charles Ray, even when he sticks to a single sculpture in a room. Like many of the most important sculptors before him, size, scale and space have been core concerns of his since the late 1980s, and he has kept his investigations of them idiosyncratic and unpredictable by taking his time. In all of my years of seeing many of his exhibitions, I don’t remember a circumstance in which he claimed space as a power grab. Instead, Ray regards space more as a topic of discussion, a philosophical dialogue or debate, orchestrated to take apart critical issues and then put them back together in an almost always genius way. With this survey of eighteen works produced between 1997 and 2014, currently on view at the Art Institute of Chicago, Ray has been given an ideal situation to provide a level of contemplation rarely achieved by contemporary art these days. In no uncertain terms this show reminds us that, yes, patience is still a virtue.

So is persistence. My first experience with one of Ray’s sculptures in 1989 has stayed with me ever since. Situated alone in one of the rooms of Feature Gallery when it was in Soho in New York, Tabletop (1988) provoked me at the time to write, “We’ve probably never been asked to look so hard at any of these objects.” The things in question—a plate, glass, bowl, canister, saltshaker, and potted plant—were on what I called then “a Bonnard breakfast table,” and were all turning at a pace that was barely perceptible. It may be that I still think of this sculpture as one of Ray’s best—mainly because it was, so to speak, my first time—but it remains for me a kind of visual and mental slow-burn explosive device; mind-blowing and understated all at once.

Ray’s mid-career survey that traveled the United States in 1998 effectively encapsulated his work up until that time (I saw it at all three venues), but it seems as well that it helped the artist sharpen his focus while slowing himself, and then us, way, way down. The decision to de-install the Art Institute’s contemporary collection and open up the second-floor space by reconfiguring it into three large galleries is brilliant for at least two reasons. The first would be lost on the first time visitor, but notwithstanding I found the memory residue of the galleries’ presentation of history poignant: the temporarily-missing Donald Judd acts as a type of refined locator of space and ground, the absent Eva Hesse as a reminder of play between pictorial and actual space, etc. That Ray’s well-known Hinoki (2007) stayed pretty much in place helps here—the timeless and time-consuming recreation of the fallen log is recast as a witness to monumental change. For all of us, however, the installation creates a dynamic environment for the significant space between everything; the entire situation is transformed into what I have taken to be a kind of morality play about the ways in which a lot of big ideas about absence, form, mass, presence, and space all matter now more than ever.

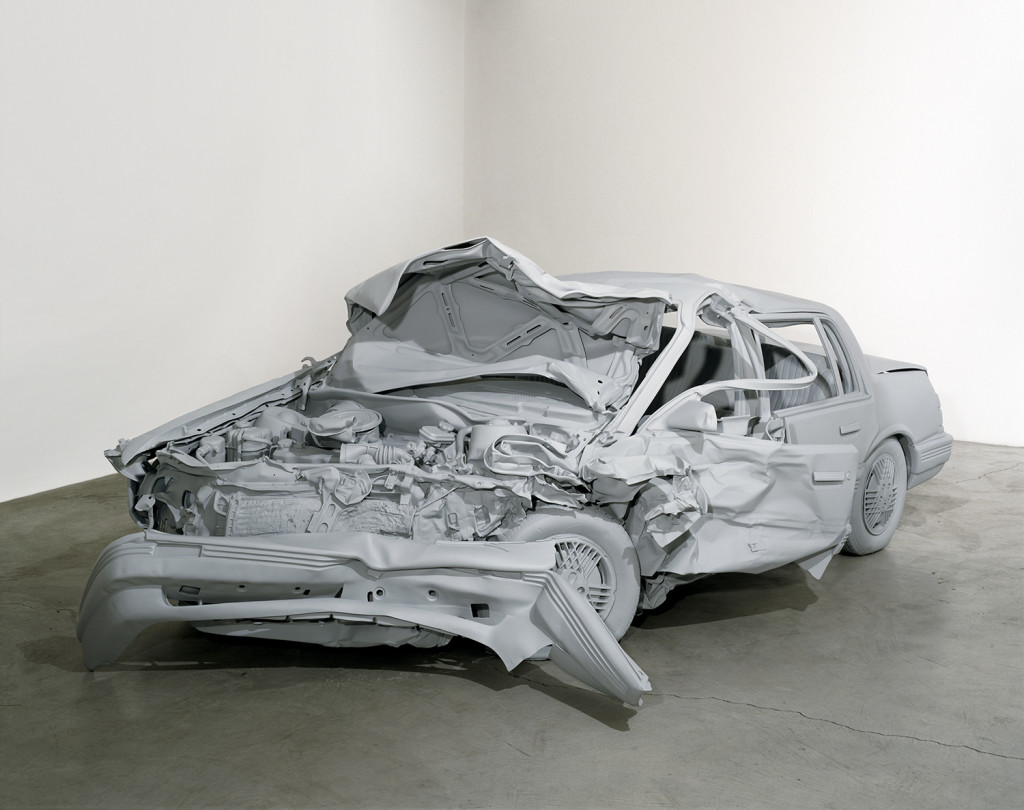

The seriousness of these ideas is what makes Ray’s focus on figuration all the more potent. A quick glance into these galleries could lead us to jump to the conclusion that we had traveled back in time, into the comfort zone of the monument: the statue in all of its historical meaning and specificity. By starting the chronology of the exhibition with Unpainted Sculpture (1997), a painted-in-gray fiberglass work based upon a car that had been involved in a fatal crash, Ray anchors its missing human body as its own kind of grounding presence, eternalizing a violent and fleeting moment, and making it shockingly serene. It is this almost tangible sense of serenity that hit me hardest in this exhibition, a quietude that doesn’t sacrifice intensity, but rather puts it to work, whether in the almost vibrating sharpness of Tractor (2005), the pristine smoothness of The New Beetle (2006), the solid liquidity of Mime (2014), or, most dramatically, the complicated yet calming transcendence of Huck and Jim (2014). Even though this last sculpture is the only one in the exhibition not installed to provide for what still comes across as its full potential (placed in a niche outside one of the entrances to the large galleries), it presents itself as a triumphant masterpiece for our time right now, condensing all that is powerful about Ray’s work into that space between Jim’s outstretched hand and Huck’s back. It speaks volumes.

Charles Ray: Sculpture, 1997–2014 at the Art Institute of Chicago runs through October 4, 2015.