Claudia Wieser: Structural Rhythm and the Interweaving of History

by Rachel Adams

“(Art) history unfolds in spirals, jumping back and forth. There is no such thing as a linear development, at least if you have a closer look.”—Yilmaz Dziewior1

Claudia Wieser’s artworks are the results of inspiration taken from spheres including architecture and design, spirituality, and performing arts. By developing visual relationships between Wieser’s works and artists from across time, I hope to highlight the important role influence can play in an artist’s work and the ways Wieser culls a variety of references from public art and architecture, the history of painting, craft, and theater to create new experiences though the balanced rhythm of interacting forms. With her wallpaper works, Wieser carefully stitches together a constellation of disparate elements. Similarly, this essay gestures toward a new understanding of Wieser’s work through its relationship to history.

“I believe it is possible that, through horizontal and vertical lines constructed with awareness, but not with calculation, led by high intuition, and brought to harmony and rhythm, these basic forms of beauty, supplemented if necessary by other direct lines or curves, can become a work of art, as strong as it is true.”—Piet Mondrian2

Most of Wieser’s work is abstract, linked closely to the structured and regimented history of geometric abstraction. While there can be a certain looseness in her mark-making—as seen in her drawings, hand-painted tiles, and sculptures—her designs often lean into structure. They are usually not symmetrical, which supports Wieser’s goal of wanting to move beyond just the aesthetic in her work. In examining the practices of Josef Albers (1888–1976), Elsi Giauque (1900–89) and Lygia Pape (1927–2004), a clear connection emerges with the formal qualities of Wieser’s contemporary artworks, even with a century separating their creations.

While more prominently known for his homage to the square, Albers began his student career at the Bauhaus assembling collages from pieces of broken glass.3 Park, c. 1924, was a turning point for Albers. In this work, Albers created a logical system for organization based upon distinct groupings of colors. The metal strips create a framework for each rectangle of colored glass, and while no uniform pattern emerges—much like Wieser’s Untitled, 2020, commissioned for “Generations”—the composition and architectural lines generate an expressive effect. The formal qualities of Wieser’s ceramic tile works rely heavily on the interaction and connection between colors to seduce the viewer similar to the way Albers’ Park does.

While Wieser’s affinity with the Bauhaus has been explored,4 her close connection with other pioneers of geometric abstraction is not as widely studied. Fiber artist Giauque created works that can be put in clear conversation with Wieser’s. Giauque’s significant but under-recognized early works, including Blau-Rot, 1925, are critical pieces in the intersecting histories of fiber art, modernism, and geometric abstraction.5 Artworks like this one resonate deeply with Wieser’s drawings and ceramic works through similar geometries, combinations of forms, and color palettes. Wieser’s work also parallels the Brazillian Neo-Concrete movement, which included artists Lygia Clark, Hélio Oiticica, and Lygia Pape. In particular, Pape’s Book of Creation, 1959–60, shares significant formal elements with Wieser’s ceramic tiles, though in three dimensions. By merging architecture and design elements with visual mediums like fiber, ceramics, and painting, Giauque, Pape, and Wieser all find new ways to materialize space through formal abstraction.

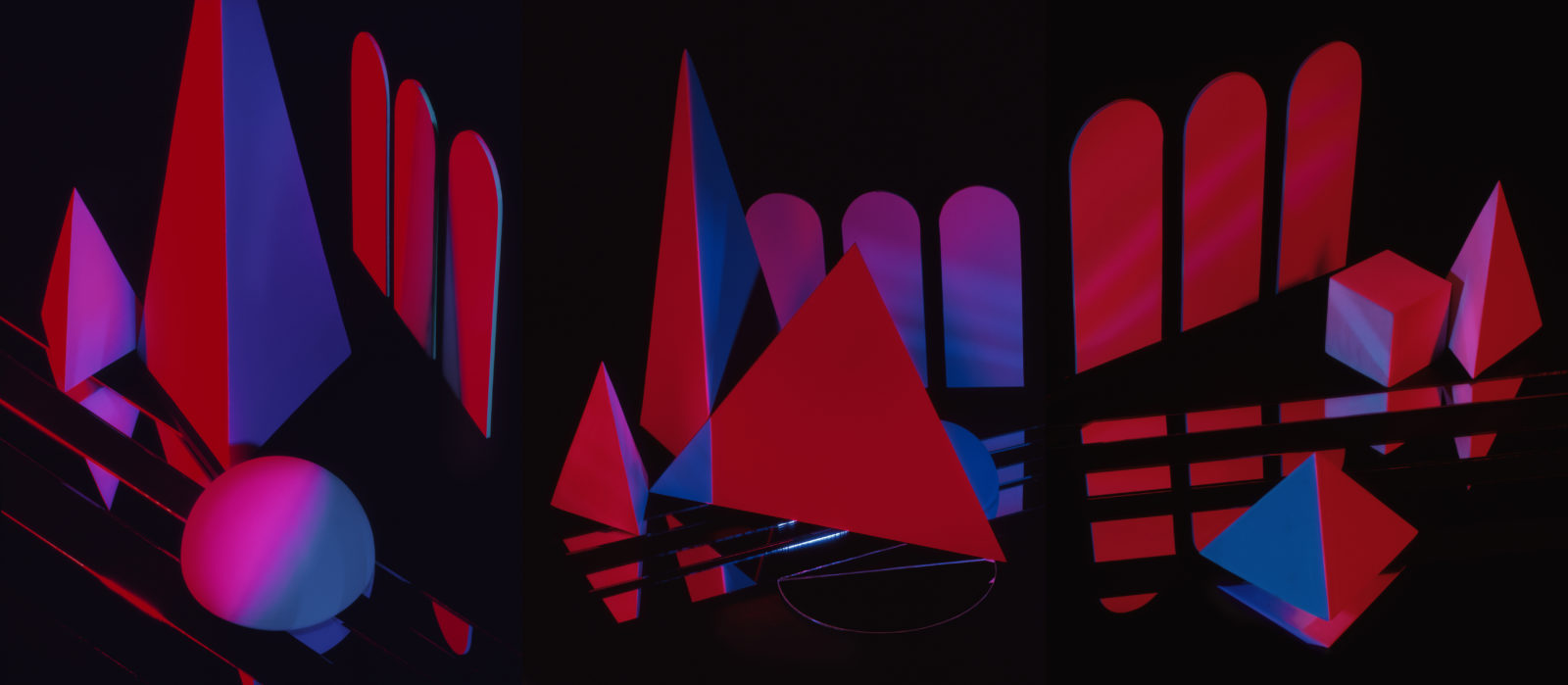

“It’s about how materials interact with light and how light is so essential to the way that we look at the world.”—Barbara Kasten6

The architectural qualities of light figure deeply into Wieser’s practice. Provoking the viewer and simultaneously placing them directly into the work through multiple angles of reflections, Wieser plays with visual ambiguity, never ceding one correct vantage point from which to view her work. Her fractured mirrored surfaces and sculptures create new experiences from different angles and use light to transform spaces into forums where the artist’s interests in fine art, architecture, design, theatre, and film collide.

In a 2010 exhibition at New York’s Drawing Center—“Poems of the Right Angle,” curated by Joanna Kleinberg—Wieser engulfed the exhibition space with greyscale prismatic wallpaper that looks like textured wall rubbings and creates oscillating shapes resembling slivers of light. Paired with a ceramic and mirrored wall relief, this wallpaper, originally created in 2004, echoes deeply into art history. The sculptural wall relief bears a resemblance to German artist Fritz Winter’s 1934 oil painting Light Breaking Through, which is part of a series called Licht-Bilder, or light pictures, focused on the refraction of light through crystals. In this body of work, one can see how “light and materiality coincide, overlap and even switch places,”7 as writer and critic John Yau puts it, and the visual twinning between Winter’s painting and Wieser’s installation at the Drawing Center creates a new way of looking at these works in their own contexts.

The Drawing Center installation is part of an ongoing exploration Wieser began in 2008 that involves mirrored surfaces. Emulating a technique she discovered in Paris by Art Deco architect Robert Mallet-Stevens (1886–1945) using fractured, stacked mirrors to reflect space, Wieser has created both reliefs and sculptures in the round that visually rupture the spaces in which they reside. Mallet-Stevens is known for uniting elements of Modernism based on historic traditions while integrating an avant-garde vocabulary of Cubism and Futurism into his designs.8 Similar to Mallet-Stevens, who also designed stage and film sets as well as grand architectural interiors, Wieser uses space to create non-linear narratives that change depending on who inhabits the space and how they physically move through the exhibition.

“To embellish buildings was once the noblest function of the fine arts; they were indispensable components of great architecture…Architects, painters, and sculptors must recognize anew and learn to grasp the composite character of a building both as an entity and in its separate parts. Only then will their work be imbued with the architectonic spirit which it has lost as ‘salon art’.”—Walter Gropius9

Wieser’s exhibitions often reference theater and present a sense of drama, wherein the viewer becomes another layer in the work. With many of her presentations, she creates all-encompassing experiences in an exhibition space, fabricating a place of interaction while paying homage to her many inspirations. Influenced by Wassily Kandinsky’s (1866–1944) Music Room, Deutsche Bauaustellung, 1931, in which the artist sought out to offer an alternative to the “blank wall.”10 Wieser’s seemingly undulating wallpaper constructions often comprise photographs of her works included in the actual exhibition, mirrored refracted surfaces that break up the space, and ceramic tile works adding bright color and sheen to the work. Compositional doubling, layering, and reflection add to the viewer’s experience of taking part in a production. Similar to the theatricality found in de Stijl artist Theo van Doesburg’s (1883–1931) Cafe Aubette’s cinema and ballroom design,11 Wieser’s installations and exhibitions—with their rhythmic balance of form, color, and the presence of the artist’s hand—synthesize her work and the architecture of the surrounding space.

“The pictures are theatrical inasmuch as they are about staging and artistic ‘play.’”—Andy Grundberg and Julia Scully on Barbara Kasten12

Much like the work of Barbara Kasten (b. 1936), who builds, stages, and photographs architectonic vignettes from a variety of materials, Wieser creates situations within her installations that feel stage-like and often imagine visitors as characters and small sculptures as props. While Kasten’s Constructs series from the early 1980s “referenced constructivism through temporary theatrical tableaus that were then photographed,”13 both artists focus on dressing the stage as much they explore concerns of dimensionality and materiality within the work.14 In Wieser’s installations, the props take on a multitude of forms and colors that imbue the space with a certain drama, especially in relation to Wieser’s wallpaper designs and the fractured mirrors reflecting the space back in on itself. From a distance, her sculptures appear almost flat, allowing one to see the connection with her drawings and opening up a conversation with Constructivist ideas of form and design.15 Kasten has been known to show both her three-dimensional Constructs installations as well as the photographs made of them in the same place, and Wieser does something similar by integrating photographs of her past work into her wallpapers. Both artists create a loop, playing within time and space.

“Her paintings are models meant to help guide the viewer towards a higher state of consciousness — deeply imaginative, syncretic amalgamations of af Klint’s beliefs and research into esoterica and science.”—John Yau on Hilma af Klint16

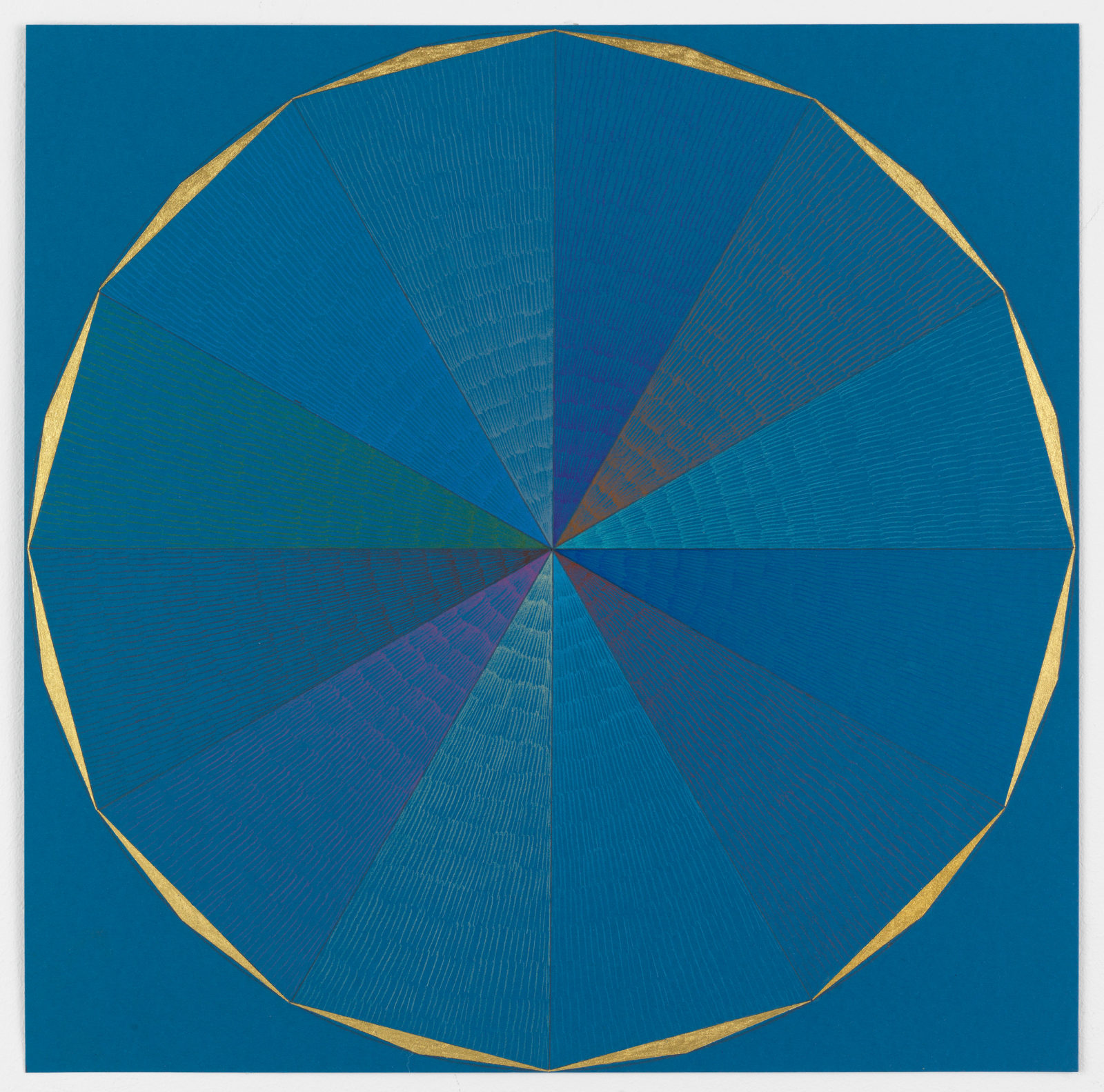

In Kandinsky’s On the Spiritual in Art (1911), the artist discusses how color and form can create a symbolic language that can stir the human soul.17 Employing materials such as metal, gold, ceramic, and wood, which have a storied tradition throughout the history of art, Wieser makes a definite nod toward ideas found in spiritualism throughout time. Repeating shapes and patterns, both religious and secular, that oftentimes refer to sacred geometry, Wieser engages with ideas found in mysticism and spiritualism—and with artists who have employed similar techniques before her.

The works of Hilma af Klint (1862–1944) speak to an effort to “find visual expression for a transcendent, spiritual reality beyond the observable world.”18 Af Klint developed her style—which varied from simplistic, monochromatic works to complex compositions of shapes, lines, colors, and words—over time through the influence of Theosophy, the educator and visionary Rudolf Steiner, and studies in modern science.19 Many, if not most, of af Klimt’s works “contain symbols, signs, language, diagrams, biomorphic forms, color charts, and geometric shapes.”20 Specifically, Group X, No. 1, Altarpiece, 1915,from af Klint’s series Paintings for The Temple, which was planned for an installation in a spiral temple, is an example that includes a combination of these elements relating to spirituality.

Paul Klee (1879–1940), who also had an interest in spiritualism, explored geometry through repetition, pattern, and color, employing his own personal symbolism. His work often contains references to unity, transformation, growth, and time: “It is the artists’ mission to penetrate as far as may be toward that secret place where primal power nurtures all evolution…In the womb of nature is the primal ground of creation where the secret key to all things lies hidden.”21

Wieser’s work has similar meditative and awe-inspiring qualities to those found in the works of af Klint and Klee. The practices of all three artists speak to metaphysical possibility through their respective abstract pictorial languages. The formal style of Wieser’s compositions speaks to transformation of space and, by pushing the bounds of her abstract vocabulary, Wieser opens the door to spirituality and religion.

“It is a sense of place and the orchestration of a person’s passage through it, with which she is concerned”—Nancy Princenthal on Jackie Ferrara22

While Wieser exhibits her work in white-walled galleries and museums, there is a major public and architectural component ever present in her practice. Wieser has an intuitive understanding of space and how to enhance or expand it visually—whether a gallery, a hallway, or a swimming pool. At the Bauhaus, Walter Gropius was reticent to allow women to practice architecture and instead steered them toward weaving, pottery, drawing, and photography.23 While that gendered division has of course changed in art schools today, many female artists such as Wieser, Jackie Ferrara (b. 1929), and Joyce Kozloff (b. 1942) combine architecture with design and decorative arts to amplify spaces. As Kozloff states, “The intention is to be both unique and familiar, combining traditional design elements in an interrelationship that is vast without being imposing.”24 All three artists work with ideas and materials to transform the environment, inviting aesthetic experiences that are both visual and spatial.

Across her practice, Wieser’s work mines and expands upon cultural histories, creating balanced compositions that marinate her classically Modernist style with spirituality and antiquity. Wieser’s installations act as spatial, three-dimensional collages, combining sculpture, wallpaper, drawings, ceramic, and mirrors—creating a new space. There are thousands of connections to be made between all the materials, lines, reflections, and geometric forms within Wieser’s practice.

Utilizing the process of collage as a starting point, the aim of this text is to expand upon Wieser’s influences and inspirations through vignettes that include touchpoints throughout history that relate to her practice formally, aesthetically, and conceptually. Presenting Wieser alongside af Klimt, Kandinsky, Kasten, Ferrara, Kozloff, Pape, Giauque, Winter, Mallet-Stevens, Klee, van Doesburg, and Albers, hopefully illuminates the multiplicity of art and how ideas can overlap across generations and continents.

This text was published on the occasion of Claudia Wieser: Generations and a program hosted by EXPO CHICAGO in collaboration with the Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago and the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts.

Claudia Wieser: Generations is on view at the Smart Museum of Art through December 13, 2020.

- Yilmaz Dziewior, interviewed by David Maljković, Exhibitions for Secession (Vienna: Secession, 2011), 34.

- “A Movement in a Moment: De Stijl,” Phaidon, accessed Sept. 20, 2020, https://www.phaidon.com/agenda/art/articles/2015/may/12/a-movement-in-a-moment-de-stijl/.

- “Albers and Moholy-Nagy: from the Bauhaus to the New World, room guide, room 1,” Tate, accessed Sept. 20, 2020, https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/albers-and-moholy-nagy-bauhaus-new-world/albers-and-moholy-nagy-0.

- See Jennifer Carty’s essay in the catalogue, Claudia Wieser: Generations.

- Gallery guide from “Fiber: Sculpture 1960–present” (Boston: Institute of Contemporary Art, 2014).

- Millie Walton, “Boundary-breaking artist Barbara Kasten on light & perception,” Lux Magazine, Summer 2020, https://www.lux-mag.com/boundary-breaking-artist-barbara-kasten-on-light-perception/.

- John Yau, “Fritz Winter’s Crystalline Vision,” Hyperallergic, Jan. 27, 2013, https://hyperallergic.com/64046/fritz-winters-crystalline-vision/.

- Jean-François Pinchon, Rob Mallet-Stevens: Architecture, Furniture, Interior Design (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991).

- Walter Gropius, “Programme of the Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar” in Programs and Manifestoes on 20th Century Architecture, ed. Ulrich Conrads (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1971), 49.

- Clark V. Poling, “Kandinsky at the Bauhaus in Dessau and Berlin, 1925–1933,” in Kandinsky Russian and Bauhaus Years 1915-1933, ed. Clark V. Poling (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 1983), last accessed Sept. 20, 2020, https://issuu.com/artsfblog1/docs/kandinsky_-_russian_and_bauhaus_yea.

- “Café Aubette, Strasbourg, France,” Museum of Modern Art, last accessed Sept. 20, 2020, https://www.moma.org/collection/works/976.

- Andy Grundberg and Julia Scully, “Currents: American Photography Today,” Modern Photography (October 1980): p 94.

- “Construct,” Barbara Kasten, accessed Sept. 20, 2020, http://barbarakasten.net/category/construct/.

- See Alex Klein, “Pictures and Props” in Barbara Kasten: Stages, ed. Alex Klein (Zurich: JRP | Ringier, 2015), 105.

- See “Constructivism,” Tate, accessed Sept. 20, 2020, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/c/constructivism. Constructivism was a branch of abstract art founded in Russia by artists Vladimir Tatlin and Alexander Rodchenko in Russia around 1915. The following is from their manifesto published in 1923: “The material formation of the object is to be substituted for its aesthetic combination. The object is to be treated as a whole and thus will be of no discernible ‘style’ but simply a product of an industrial order like a car, an aeroplane and such like. Constructivism is a purely technical mastery and organization of materials.”

- John Yau, “Hilma af Klint, Outlier for the Ages,” Hyperallergic, Nov. 25, 2018, https://hyperallergic.com/472426/hilma-af-klint-paintings-for-the-future-solomon-r-guggenheim-museum/.

- Wassily Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1977)

- Tracey Bashkoff, “Temples for Paintings” in Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future, ed. Tracey Bashkoff (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2018), 17.

- Ken Johnson, “The Modernists vs. the Mystics,” New York Times, April 12, 2005, https://www.nytimes.com/2005/04/12/arts/design/the-modernist-vs-the-mystics.html.

- Yau, “Hilma af Klint.”

- Paul Klee, On Modern Art (London: Faber and Faber Limited, 1948), 51.

- Nancy Princenthal, “Placemakers: Jackie Ferrara’s Public Art” in Jackie Ferrara Sculpture: A Retrospective (Sarasota, FL: John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, 1992), 76.

- Mark Hinchman, “Women of the Bauhaus” lecture, Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Omaha, NE, April 23, 2020.

- “Joyce Kozloff: Humboldt-Hospital Station, Buffalo,” Joyce Kozloff, accessed Sept. 20, 2020, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/54cfdb3fe4b0f3f8e9b51f03/t/54effea2e4b027e12ca4f80a/1425014434843/Buffalo.pdf.