Collective Consciousness: Mark Baum at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center

by Leah Gallant

In 1961, the painter Mark Baum moved from New York City to Cape Neddick, Maine. The artist was dissatisfied with the New York art world and its turn to abstract expressionism. In the 19th-century barn he took as his studio, he spent the next eleven years perfecting a single geometric shape, which he referred to as “the element.” This runic mark became the basis of his paintings for the rest of his life.

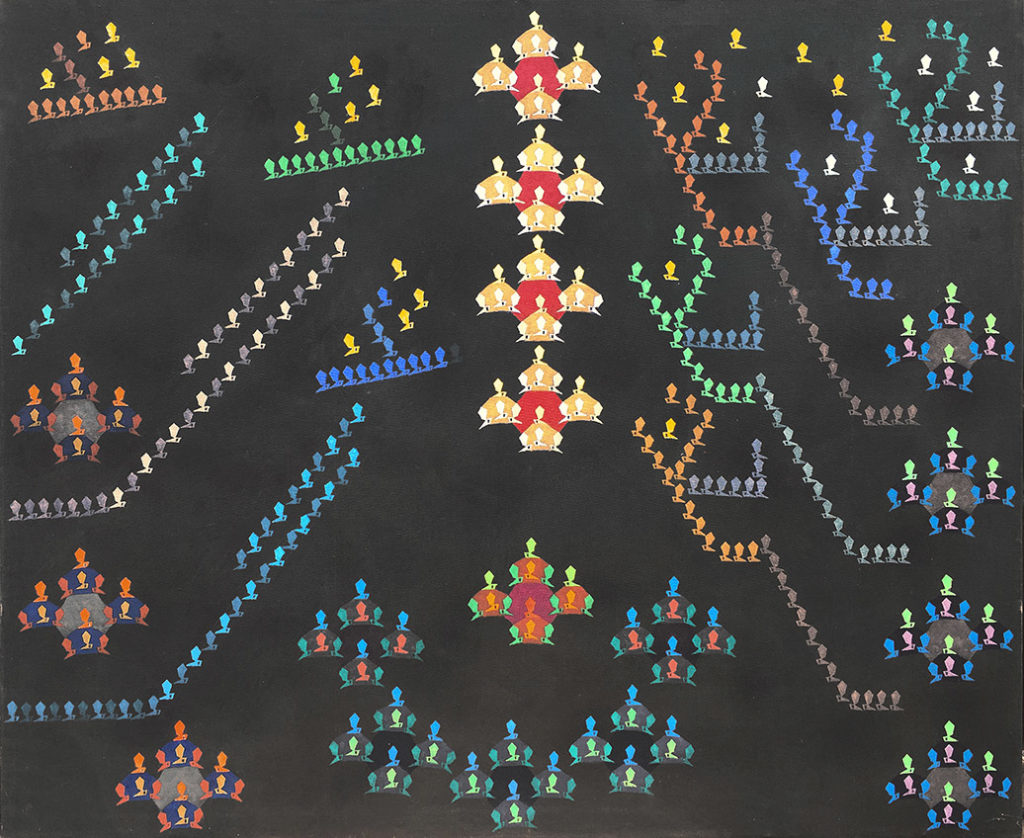

The element morphed over time. In one iteration, this form resembled the silhouetted bust of Nefertiti; in another, a moth flying in profile, raising one clunky wing, a single eye delineated. By the time of his death in 1997, Baum had completed scores of canvases covered in drifts of these small technicolored marks, in different embroidery-like patterns reminiscent of the pixelated aliens of early video game Space Invaders.

Baum, who was Jewish, was born in 1903 in a small village in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in present-day Poland. At the age of sixteen, he fled across Europe on foot, passing through Poland and occupied Germany. When he arrived in New York City in 1919, he found work as a furrier, cutting pelts into coats to support himself and his family. He quickly established himself as a painter, showing at the Whitney Studio Galleries, the predecessor of the Whitney Museum, and moving in the same circles as Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, Leo Castelli, and Alfred Stieglitz. Although he took classes at several art schools, he remained largely self-taught.

Several of Baum’s early paintings from the 1940s—small paintings of houses ensconced in shrubbery and other quiet, representational scenes—open the 2019 exhibition Collective Consciousness: Mark Baum at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. In his early work, plants and lights are rendered with a Rousseau-like bizarro precision. In Still Life with Fruit and Lamp (1946), the pull of the grids of building windows in the background and the zips of blue and yellow lines of a tablecloth’s border electrify the staid bananas and apples. In a key painting he made two years later, Aspirational Staircase (1948), the zigzagging stairs seem to emanate light. They are the subject of the canvas, a sort of divine architectural being. Cloud-like shapes loom in the sky behind them: swarms of wasps or continents of thumbtacks adrift. They herald Baum’s turn towards the building of mass with repeated small marks. Here they are still small, brushstroke-sized marks, like bird tracks or ants marching in abstracted step.

From there, beginning in the sixties, it was all elements all the time.

Baum arranged these forms, each approximately one by one and a half inches large, in lines and swarms of multicolored patterns against black grounds. Sometimes the elements face left and sometimes they face right, and sometimes they are tilted diagonally, but they are never upside down, and they are always lined up with their brethren. In some, the clusters of elements have background patches of colored five-sided shapes, but by the last few decades Baum had pared his compositions down to pure elements fending for themselves against a black ground.

Some compositions play with left-right symmetry, only to veer away; some element-armies suggest representational forms. In Life Span, they appear like an enormous bird twisting one wing up and the other down; in Celebrating Growth (1984), they resemble the stylized Gothic “T” of the New York Times Magazine. The patterns of forms are entrancing. I saw in them the Aurora Borealis, the Paracas textiles with the flying shaman patterns, and aerial photos of large-scale choreographed movement, like an Olympic opening ceremony.

Baum could have stamped his elements, but he painted each one individually. There are moments of unevenness in the paint application, of wings that expand a little too far left, and traces where a quarter of an inch of paint has been scraped off the canvas. Their unpredictability, even within the constraints, makes them runic and portentous. The ends of each canvas seem somewhat arbitrary—each painting could be a fragment from one long cycle of tapestries or murals, wallpapering some antechamber like a coastal Maine take on Goya’s black paintings.

Although he returned to New York in the winters, and showed at Bleecker Gallery in 1962, Baum’s work with the elements was rarely exhibited during his lifetime or after his death. Baum is one of many examples of the arbitrary distinctions between artist and “outsider” artist. He knew the dominant trends in contemporary painting, and he participated in them, but he wanted something else. His work seems to communicate this faith. They are small moments of public service made for a dark and disordered world: not Goya’s tortured black paintings, but a greenhouse of symbols. Baum was a visionary artist, and he also knew exactly what he was doing.

On the left-hand side of 1994’s Welcoming Truth, the last painting in the exhibition, two wavering lines of butter-yellow elements face into a lagoon of the glyphs. The title is optimistic, but the image is ominous. Are they the unknown, or a waiting crowd, or a cultish circle of beings? They are the elements, pingponging around an expanse of black space, each one fitted to its neighbors like a chainmail of sequins or little luminous beings.