Complicated Beauty: Contemporary Cuban Art

by Brian Prugh

Yoan Capote is quoted in the wall text by his painting as saying, “The sea, for me and for a lot of Cubans, was like a wall, more an image of isolation than a beautiful place. I grew up with a frustration about the limitation and an obsession about crossing the sea.” This idea situates the title of this survey of contemporary Cuban art, Complicated Beauty, currently on view at the Tampa Museum of Art, organized in collaboration with the Bronx Museum of the Arts—the sea, a paradigm of beauty, is complicated when it becomes a barrier or an obstacle.

Capote’s painting, Isla (Umbral) (2015), is a night seascape with the sky painted in thick, black oil paint, the horizon a line of tiny, rusty nail heads, and the sea a swirl of fish hooks. The fish hooks create a surface at once sinuous, shimmering and prickly—dangerous. It places the natural boundary within a political context perhaps a little too easily, but effectively, implying that a more romantic vision of the sea depends upon not being trapped by it.

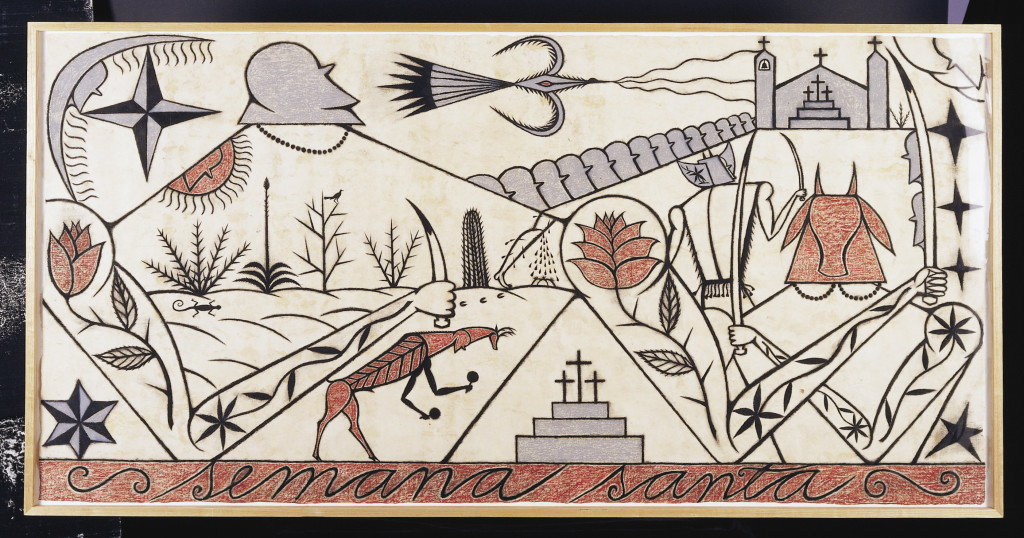

A number of works in the exhibition play with this idea of a fraught paradise—the “island getaway” for tourists whose tropical appeal is at odds with a more difficult experience for the full-time inhabitants. Sexual tourism (Sandra Ramos’s Naufragio (2008)), decaying urban spaces (Quizqueya Henriquez’s Espacio Publico photographs (2000-07)) and Cuba’s colonial history (José Bedia’s Nkumbe Makaró Ambuata (1996)) figure prominently in this exhibition’s vision of Caribbean life. Maria Elena Gonzalez’s Corrected Palm (2016) formally enacts this tension: a photograph of a palm tree is littered with holes, literally puncturing a pristine surface image associated with Cuba.

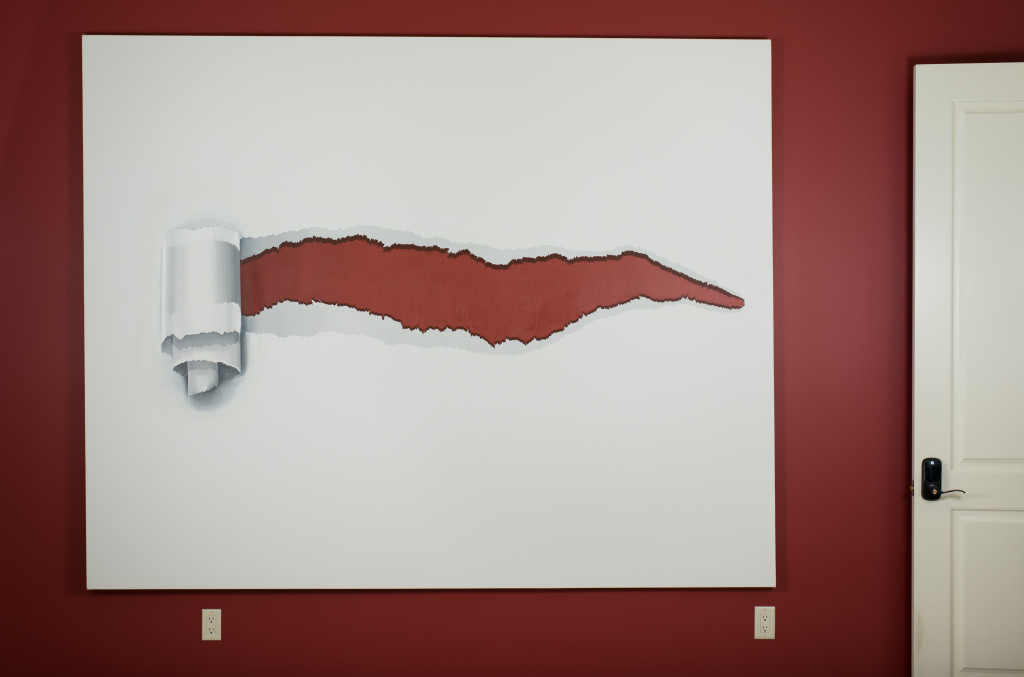

Related to this, a second major theme of the exhibition is escape or migration. Two works explicitly address migration by boat: Kcho’s A Group of Cubans Who Left Manzanillo are Rescued at Sea (2014) and Pedro Pablo Oliva’s The Great Journey (2014). Esterio Segura’s works use the airplane as a primary metaphor. Something of a nomad myself, I appreciated Abel Borroso’s Home (2012)—an oversized wooden house-backpack—although his Visa Machine, an image of a machine dispensing Visa cards and visas, reinforces the ways that international travel is dependent upon funds and government approval. Sandra Ramos also addresses the bureaucratic hurdles to travel by working with the passports of friends permitted to leave Cuba. In Horizontes (2012) an oversized Cuban passport with the skyline of lower Manhattan as a background image for visa stamps, connects the world outside of Cuba with the bureaucratic system within it that can allow or deny travel at will.

Videos by José Angel Toirac and Tania Brueguerra are overtly political, while Untitled (Decapitated Angel) by Carlos Garaicoa (1993) more ironically approaches the subject—a neoclassical angel perched atop a bannister has lost its head, the void filled by the lettering on the wall behind it: “FIDEL.”

If I were searching for what defines the exhibition as essentially Cuban, I would locate it within this interaction between the natural landscape (lush, tropical, and reminiscent of beach scenes countless US office workers place on their desktops) and Cuba’s unique political history. But it would be difficult to find a more generic formula for summing up any country’s art: what art does not reflect its landscape and political history?

That said, the particulars of Cuba’s situation create a kind of whiplash for an American audience, especially now. Last month, the art world’s jet-set were in Miami enjoying the warm weather and the palm trees, the parties, the buying and selling, surrounded by million-dollar vistas of the ocean—the same ocean that, less than 250 miles away, Yoan Capote describes as “like a wall.” And if the recent political victories of the right here chilled the atmosphere of Art Week in Miami, the chilling effect of the left-wing government to the south of us on its artists provides a sobering counterpoint to the real worries about the future that permeate the artistic community here.

In writing this review, I’ve tried to identify the sense of “Cuban art” I took away from the exhibition—the sense of place that is distinct from my sense of the place where I come from. But, perhaps unsurprisingly, the works that most moved me fall outside of the schema sketched above. José Bedia’s drawings seemed especially strong and Ana Mendieta’s Silueta Works in Iowa (1976-8) felt fresh and relevant. Humberto Díaz’s series of photographs, Libertad Condicional 01-06 (2011) are particularly striking: portraits of chairs from house courtyards that are chained to each other to prevent theft, they exist both as documents of a telling social convention and poignant metaphors for human relationships.

One of the biggest surprises, though, was Glenda Léon’s artist book, Every Sound is a Shape of Time (2015). Léon superimposes musical staves on different images: a few vultures soaring in a blue sky become notes on the staff. Similarly, the lights in a night skyline, leaves on the ground, dice thrown on a white surface, rain drops and braille dots also become notes. It is conceptually almost too straightforward—but the delicacy of the relationships between the lines and the photographs behind them rescues them from a flattening into a didactic “music is all around us” moment. A video that documents a performance based on these “scores” is intriguing, although I found that I heard different music when I looked at Léon’s scores than the pianist played. This further attests to the power of these images: they become music for me, specific music—not just an idea or signifier of music. They make me think about a comment the composer John Luther Adams made in an interview: “If I find myself in a real place, a true place, and I am paying attention, then maybe I hear something that becomes music.”

The tension in the exhibition between the place that is Cuba in its political, historical and geographic realities, and the place that the artist finds—a place that belongs to us all just insofar as we are human—is evocative and rich, giving this place-centered exhibition an impressive depth and reach.

Complicated Beauty: Contemporary Cuban Art at the Tampa Museum of Art runs until February 5, 2017.