Counter-Geography: Bouchra Khalili // Profile of the Artist

by Natalie Hegert

Deep midnight of the sky, deep blue of the sea. The following text by Staff Writer Natalie Hegert and artist Bouchra Khalili similarly flows between ‘passages,’ fluid channels that exchange voices between artist and writer, unfolding toward a singular reading between two perspectives.

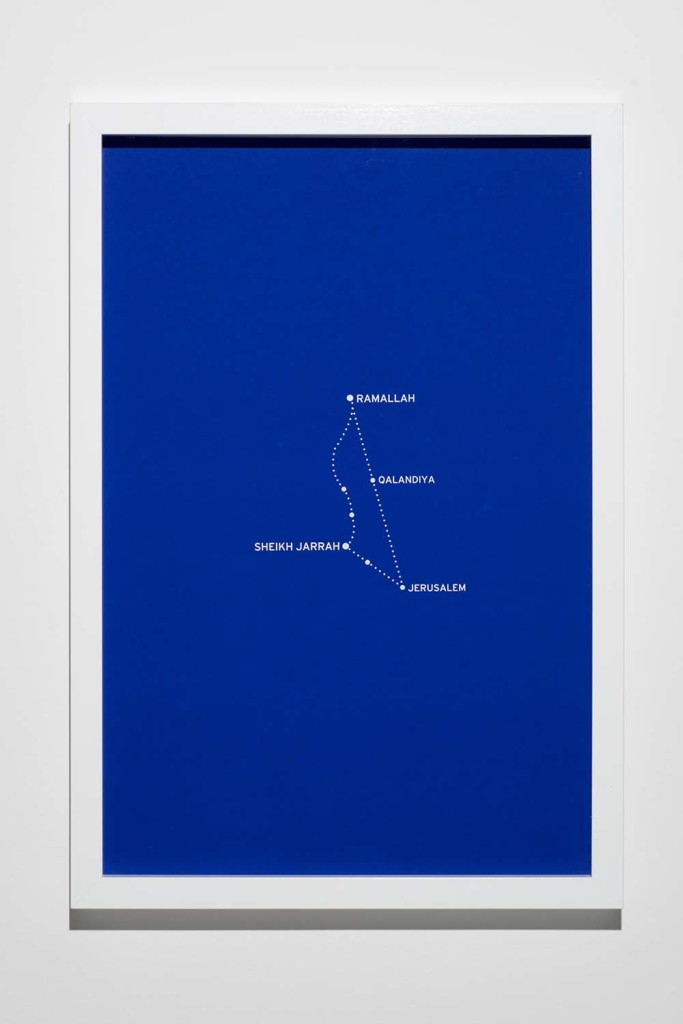

Drifting trajectories connect unnamed locations and cities that appear like stars on maps of the night sky in Bouchra Khalili’s The Constellations (2011). The series of eight silkscreen prints, translate the illegal journeys of individuals, mostly migrants, in white lines on midnight blue. Landmarks, borders, landmasses, and waterways are subsumed by its hue, revealing a subversive geography where nation-states are rendered formless, with no power to say what and who belongs where.

Each of the eight prints represents a line drawn on a map by a person recounting the details of their journey in the Moroccan-French artist’s eight-channel video installation The Mapping Journey Project (2008–2011). The narrators tell of setbacks, arrests, evasions, and deportations, while carefully marking their paths on paper. The Constellations crystallizes these details in the lines’ digressions and deviations, indicating by their meanderings the conditions of the stateless: force, compromise, waiting. But the prints’ cosmic transpositions orient these maps toward the utopic—to a borderless, free vision of the world.

The idea of The Constellations came from the articulation of language, speech, and drawings. I started with asking myself simple questions: how do you translate a journey? How to translate a subjective geography challenging borders as embodied by the nation-state model? Constellations are by essence reference points located in spaces where landmarks do not exist: the sky and the sea. As maps, they were used for centuries by sailors looking upward to locate themselves below.

Astronomers call pieces of sky where constellations can be seen “the sea.” But constellations are also visual translations of narratives: many of them are based on mythology.

Translating these forced illegal journeys into constellations of stars also aims to challenge normative geography in favor of a “human geography”—based on micro-narratives and singular lives.

The limits between the sky and the sea blur, eventually suggesting an alternative form of orientation: the landmarks are [no longer] boundaries as established by nation states, but the path of singular lives, from where the world can be seen. I have quoted it often, but I believe that Oscar Wilde was right when he wrote: “A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at.” As alternative maps of the world, The Constellations suggests a counter-geography, of singular gestures of resistance against arbitrary boundaries.

French-Martinican philosopher and poet Édouard Glissant spoke of the utopia of a world where all have the “right to opacity.” The Western method of “understanding” the Other, on the other hand, is predicated on rendering them transparent, he says. Transparency is reduction—what a wonder that President Trump not only calls for a wall to be built separating the United States and Mexico, but that this border wall must be transparent—whereas opacity allows for “irreducible singularity.” Glissant writes, “There would be something great and noble about initiating such a movement, referring not to Humanity but to the exultant divergence of humanities.”

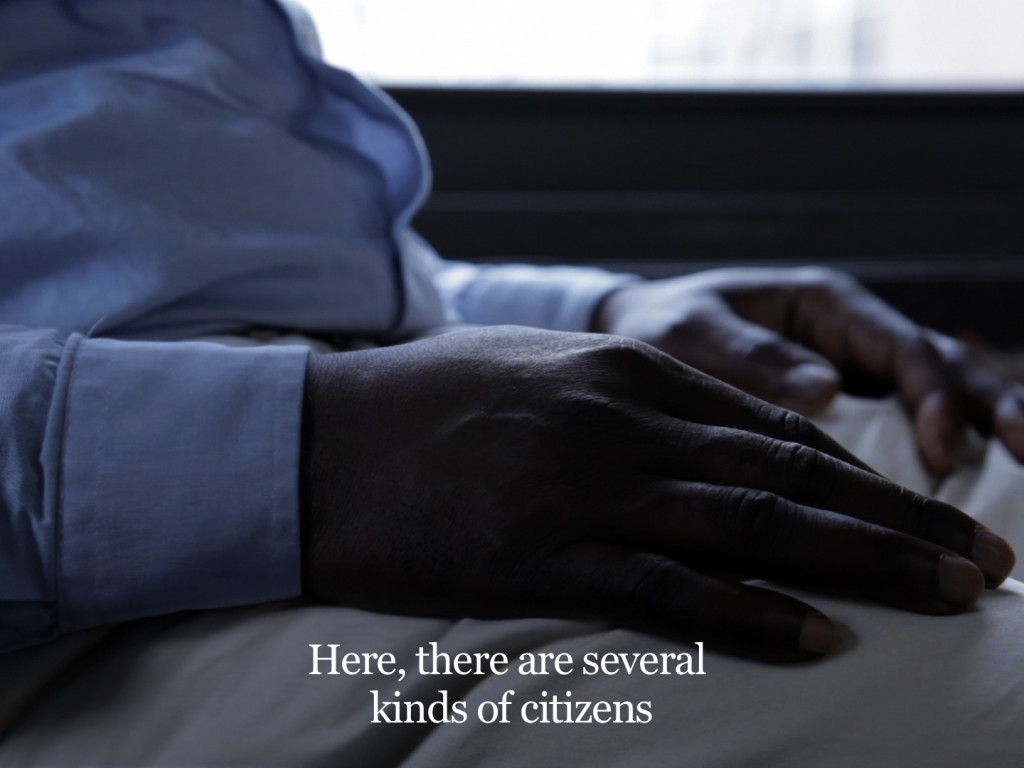

Glissant’s concept of opacity provides a vital basis across Khalili’s works, both in the representation of her subjects and in the aesthetic, cinematic choices she makes. The protagonists in her films retain opacity—quite the opposite of the exposure and reduction of minority communities for consumption through photojournalism, for instance, which, arguably reproduces and reinforces inequality. In The Mapping Journey Project (2008-2011), previously exhibited at MoMA, the faces of Khalili’s subjects are not shown; instead, the focus is drawn to what they are showing, and the sounds of their voices, speaking in their native languages. In Khalili’s works, the withholding of images paired with the resonance of voice and language becomes a strategy of resistance.

If one looks closely at my works, they all operate on a dialectics of the on-screen and off-screen, of presence and absence, relying on simple questions: what is a moving image made of? How do off-screen spaces produce an image? How do sound and words, participate in producing an image?

Behind those questions, there is of course my own belief that an image is essentially fragmentary.

That is why metonymy and deictic gestures are central in my practice: it is both about showing something to someone, while highlighting that it is a combination of fragments.

That is where opacity begins to resonate.

In the presence/absence of the protagonists shown in my works, who are often members of minorities,

there is indeed a sense of opacity preventing [their limitation] to restrictive identities, such as “migrants,” “refugees,” “undocumented workers,”…

Miami, for Bouchra Khalili: Solo Project . Video still. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Polaris, Paris.

In The Tempest Society (2017), my latest work currently on view at documenta 14, Malek, a young Syrian man living in Athens says: “being a refugee does not say what is my life.”

In this sentence, there is a gesture of resistance: he is Syrian, and indeed had to flee the war in Syria, but he refuses to be defined as a refugee, because he knows that in the use of that word there is a denial of his identity and its singularity.

As Glissant wrote, “The thought of opacity distracts me from absolute truths whose guardian I might believe myself to be.” Preserving opacity is thus an invitation, a proposal for a relation engaging with an otherness that cannot be integrally appropriated, but whose opacity is accepted and taken as such, and therefore a chance given to equality.

The recognition and acceptance of singularity does not necessarily mean each individual is an island, irreconcilably separated from others. Or, in fact, it does mean that each individual is an island, but rather part of an archipelago, or a constellation. The sea/sky is not what separates us, it is what connects us.

In Khalili’s work, the specificity of the singular draws out the concerns of the collective. In The Speeches Series (2012–13), a trilogy of videos in which individuals perform speeches addressing issues of civil rights, labor conditions, and resistance, orality serves as a locus of power, invoking Pier Paolo Pasolini’s notion of the “civil poet.” In the first video, each speaker performs in his or her native language, a gesture of resistance in the use of “unofficial” languages and unwritten dialects.

The Speeches Series started from the idea of language.

The commitment to dialects and unwritten languages was not randomly decided.

Pasolini always stated that he became a politically conscious poet when he decided to learn his mother’s mother tongue: Friulan, a dialect spoken in Northeastern Italy, at the border with Slovenia and Austria. For Pasolini, starting to write in Friulan was a gesture of resistance against a nationalist conception of normative and centralized culture.

My interest in vernacular languages and dialects is also connected to the fact that I am myself a native speaker of an unwritten dialect: Moroccan Arabic. From the beginning, I knew that what was at stake was the process of showing how a singular voice develops into a collective one, which is why the series had to shift from existing texts to authorship.

In the first chapter of The Speeches, Mother Tongue (2012–13), first produced for the Palais de Tokyo’s Triennale in 2012, five members of immigrant communities living in Paris recited historic texts, addressing theories of emancipation and resistance by Glissant, Aimé Césaire, and Malcolm X, among others. Translated into the speakers’ native languages, the piece made these historic words their own, collapsing the past and the present. The words spoken by the protagonists of the second and third chapters echo these important texts, resounding in the speeches developed and delivered based on their own experiences on immigration, citizenship, and labor.

The second chapter, Words on Streets (2013), commissioned for the 55th Venice Biennale, took place in Genoa, a location of significance as the site of the protests against the G8 summit, the “Migrants March,” and as the place where the first autonomous, self-organized group of undocumented migrants formed. The speeches, delivered in Italian by five immigrants to Italy, reverberate in public spaces as examples of this concept of civic poetry, described by Khalili as “the right taken by anyone to address society from one’s position and singularity, with one’s language, words, and voice, to call for a collective into being.”

The final chapter, Living Labor (2013), which was produced for the artist’s solo exhibition at the Pérez Art Museum Miami, and will be shown at the Palais de Tokyo and Institut français’ off-site exhibition in Chicago, curated by Katell Jaffrès and entitled Singing Stones, is sited in New York, where five undocumented workers tell of exploitative working conditions, indignity, and invisibility in the United States. Mahoma, an undocumented worker who formed a union with his colleagues, delivers a powerful line arguing for his right to recognition: “I am a citizen because my conscience grew up here.” This stinging truth undercuts the arbitrary bureaucratic distinctions of citizen and non-citizen that serve as the basis for ongoing state-sponsored discrimination and oppression, a situation only worsening as nationalist sentiment festers among the American working classes.

the artist.

In a previous interview, Khalili intimated that “what is ultimately at stake is the hope for a ‘Tout-monde,’ [a whole world] that looks beyond rigid borders and identities.”

I have always highlighted that my work is about gestures, discourses, strategies and tactics of resistance, developed and articulated by members of minorities. Looking beyond rigid borders and identities means to eventually rethink new forms of belonging and communities, freed from the nation-state narrative that is too often based on ethnic belonging and cultural and civilizational supremacy.

This Tout-monde is this call for a world opened up to fluid identities and creolization, in which equality is not a promise made by a State, but a matter of fact from the moment one stands in solidarity with one another.

By means of achieving this vision, modes of resistance, solidarity, and liberation find expression throughout Khalili’s work. Interweaving the history of emancipation—as in Garden Conversation (2014), which re-imagines a conversation that occurred in 1959 between Ernesto Che Guevara and Moroccan anti-colonialist war hero Abdelkrim Al Khattabi, and Foreign Office (2015), which explores the city of Algiers as the center of international liberation movements between 1962 and 1972—along with strategies for interrogating the conditions of the present, Khalili challenges structures of power. In her most recent work, The Tempest Society (2017), in which Athenians of diverse backgrounds gather in a theater to question society, nationalism, and forms of resistance, Khalili’s work offers a map, a leading to utopia—a land of blue sky and blue water, free from borders and oppression, where everyone speaks their own language.