David Wojnarowicz: Flesh of My Flesh // Iceberg Projects

by Jameson Paige

“When I put my hands on your body on your flesh I feel the history of that body” reads the opening of the recurring prose imprinted on multiple works in David Wojnarowicz: Flesh of my Flesh, a small but potent exhibition currently installed at Iceberg Projects. The heaviness of this sentence frames the show, where many works confront the slippery line between surface and depth, and where bodies and their absence speak volumes. Stationed in the rear carriage house of exhibition curator Daniel Berger’s home, the show garners a particular resonance in light of Berger’s long dedication to art, activism, and public health. Berger is a medical doctor specializing in HIV-related treatment who has been practicing in Chicago since the 1980s. His care for folks living with HIV/AIDS through these multiple channels comes through in the substantial supplements created for the show. An exhibition checklist thoughtfully expounds upon each piece’s significance, a film series was co-organized with Block Museum, and a significant publication titled Militant Eroticism–The ART+Positive Archives published last year finds a fitting home as reference material in the gallery. Like Berger’s multi-pronged effort, Wojnarowicz’s endeavors feel flesh and its histories are not limited to specific media. The work attempts to get close to lost bodies by any material means necessary. Though a small-scale exhibition, viewers will find almost every medium represented. The show mimics Wojnarowicz’s practice by centering a concern—here, the body in all its complexity—and working outwards to configure its intricacy in as many formats as possible.

Iceberg Projects is roughly divided into two small gallery spaces and Wojnarowicz’s works are arranged somewhat chronologically, though as a whole, the show remains porous. Works from the early to mid 1980s are relegated largely to the first room while later works coalesce in the second room. The two central points of the exhibition are the sculpture, Untitled (1984), a horse skull wrapped in a world map with allusions to time, entrapment, and futility, and the video When I Put My Hands on Your Body… (1989), a collaboration with Marion Scemema featuring Paul Smith. In the film the artist recites prose of the same title, which recurs through various print forms in other works. Wojnarowicz and Smith’s forms slowly entangle each other through cropped frames. They are softened and distanced by a blue hue which drenches their desiring kisses. One wonders if Derek Jarman’s seminal Blue (1993) took inspiration from this earlier piece. Though the video faces inward, Wojnarowicz’s powerful vibrating voice fills the gallery even when viewers are not in front of the monitor. The permeation of the artist’s voice is curatorially significant, even if it is only one element of the video. Voice is both of and in addition to the body, not unlike a haunting or ghost-like presence. Kaja Silverman states, “the voice is capable of being internalized at the same time as it is externalized, to spill over from subject to object and object to subject, violating the bodily limits upon which classic subjectivity depends.”1 The bleeding of Wojnarowicz’s voice gently floods the gallery, subsuming viewers in the lingering presence of everything but his body and melting subjective divisions as he narrates the process of looking.

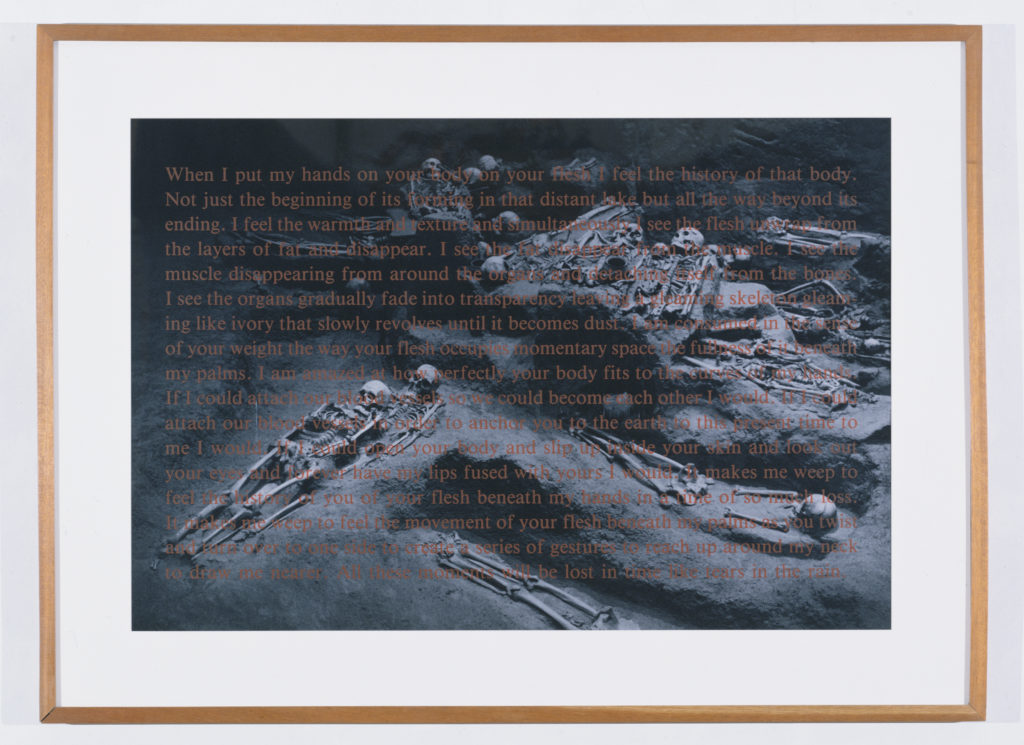

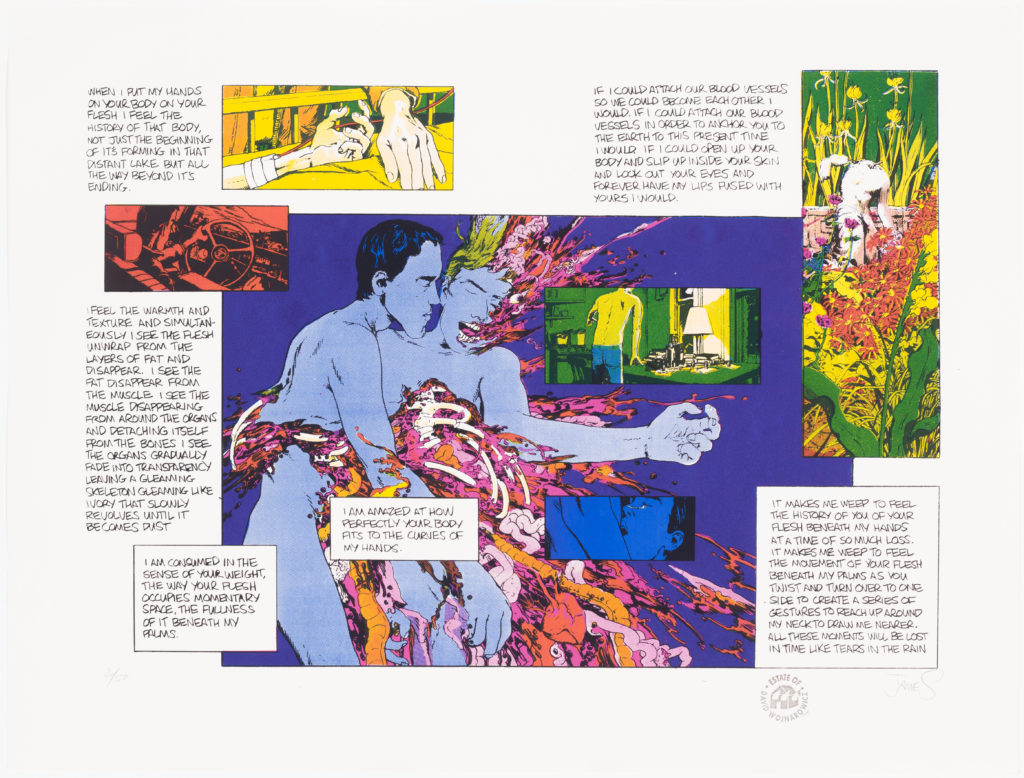

Flesh is often the physical vessel for understanding embodiment. Experience is qualified by a physical journey; the most intense trauma can be reduced to temporal corporeal effects. Anyone who has truly experienced something however, will tell you a body entails much more than flesh. Wojnarowicz’s work moves viewers to the position of understanding flesh as a means to the deepest feelings, while not leaving the immediacy of the body behind. Moments where the artist weaves text and image are the most profound indicators of bodily capacity. The late works—Untitled (1990) and When I Put My Hands on Your Body (1990)—veil a world map and colorless gravesite with his sincere prose detailing the powerful slip between flesh and feeling.

Text in these works is often printed small, directing a range of resonances: the worn pages of an old paperback; the graphic crispness of a comic strip; the officiated weight of a government document. In any manifestation, the consistency of scale requires the viewer to get close and hold space with these works, engaging their affective charge by sheer proximity. Sex Series, a set of eight prints from the late 1980s, appear as photographic negatives and collage steamy encounters with select symbology of American idealism. The negative, undeveloped quality of the images appear as an inversion of America’s good-natured veneer. A different history that was not given the time, labor, or conviction to materialize into something memorable sits magnified in its undeveloped state. Puncturing images of planes parachute dropping soldiers, bucolic homes, and New York City are sexual acts between men which recall the limited visibility of a gloryhole. In other images, such as the mushroom cloud or train racing through middle America, the piercing holes give way to blood cells, radio waves, soldiers, and money. The Sex Series reveals the paradox of sex’s simultaneous ubiquity and concealment, which once opened gives way to the myriad issues concurrent to the HIV/AIDS crisis that queer politics in the late 1980s mobilized against. The systemization Wojnarowicz created in this series edges on didacticism yet points to the legibility and urgency of activist vernacular which are, above all else, cries for recognition and change.

Though the political force of unabashed sex is on display in Wojnarowicz’s work in this exhibition, the eager politics of sex are balanced by the softness of intimate reverie and reflection. Sex sprawls out beyond the spectacle of shock, allowing wounds, sentimentality, and gentleness to also emerge. Untitled (7 Miles a Second) (1993) [with James Romberger], depicts this simultaneity. As Wojnarowicz and his lover violently explode, they are joined by both painful and pleasant memories of their time together.

The intimacy of the show’s scale can, at some points feel a bit too condensed. The works nearly swallow the viewer up through their scale and number, yet perhaps this fiery storm of desire, rage, and loss, is exactly the situation we need to be confronted with in this renewed moment of socio-political and cultural warfare. On his affinity for the camera Wojnarowicz said in 1991, “history is made by and for particular classes of people. A camera in some hands can preserve an alternate history.”2 History itself however, is often one note—a single timbre stretches the duration of a memory. Among these loaded objects, affects crop up side by side and commingle. Rather than defensively grate on each other’s edges, they illuminate a fuller picture of the extreme trauma of dying while the world watches with little care. The AIDS crisis is not reduced to an inexhaustible rage on behalf of those fighting back, though this feeling also weighs the room. Instead, the ongoing desires to touch, to continue lusting, and the longing for love—despite shortened life—are just as present in the sharp fury of Wojnarowicz’s seething works. There is much to learn in this quiet backyard.

Flesh of My Flesh is open at Iceberg Projects until August 3rd.

- Kaja Silverman quoted in Norie Neumark, “Introduction,” in Voice: Vocal Aesthetics in Digital Arts and Media, ed. by Norie Neumark, Ross Gibson, Theo van Leeuwen, (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2010), xix.

- David Wojnarowicz quoted in David Wojnarowicz: Brush Fires in the Social Landscape, ed. Melissa Harris, (New York: Aperture Foundation, Inc., 2015), 1.