Dead Images: Tal Adler // Profile of the Artist

by Ruslana Lichtzier

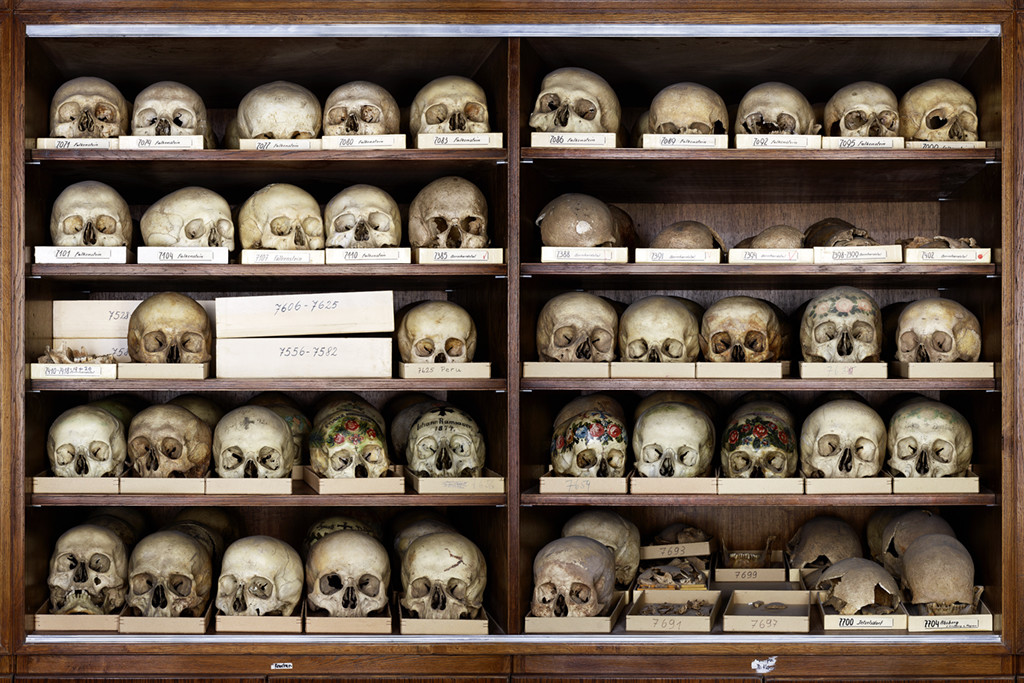

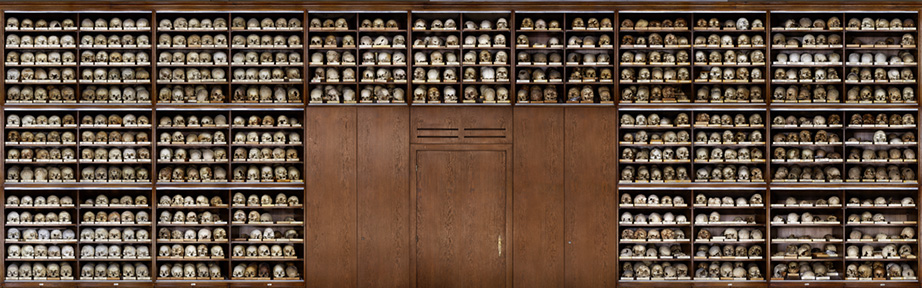

Dead Images is the title of just one of the multi-disciplinary teams presented as part of ‘TRACES: Transmitting Contentious Cultural Heritages with the Arts, from Intervention to Co-production,’ a three-year multi-disciplinary research project from eleven European partners that investigates the role of contentious heritage in contemporary Europe. Dead Images addresses the implications of human remains exhibited and stored in museums and institutional collections, often hidden from the public eye. The heart of Dead Images is a 1:1 scale panoramic photograph of a cabinet with human skulls. Thirty meters long, and three meters high, over 8,000 human skulls are displayed within the picture. The site of the photograph is located in the collection of the Anthropology Department of the Natural History Museum in Vienna, a restricted access area. The image reveals only a fifth of the entire collection of over 40,000 skulls, and is in many ways an anchor of the multi-disciplinary international research project led by a team of six individuals: artist Tal Adler; art historian Anna Szoeke from the Humboldt University in Berlin; Osteoarcheologist Linda Fibiger; artist Joan Smith; social anthropologist John Harries from the Edinburgh University; and former head of the Anthropology Department at the Natural History Museum in Vienna and physical anthropologist Maria Teschler-Nicola.

Tal Adler, an artist and inter-disciplinary researcher, is the photographer behind the panorama that defines Dead Images. He is also the designer and coordinator of the ‘Creative Co-Production’ teams (CCPs) for TRACES, and a member of one of the CCPs that focuses on the philosophical, aesthetic, historical, and scientific implications of human skulls in public collections. I spoke with Adler to discuss his practice, below is a transcription of the conversation.

Ruslana Lichtzier: It seems to me that the fact you chose to work within the photographic medium forced you towards a research base practice. Can you expand on this? What made you turn inwards and ask questions regarding the medium itself, its histories and its practices, and then turn back, outwards, to apply the same questions toward other disciplines?

Tal Adler: I am not really sure what happened first. It might be that the research potential, which is inherent to photography, drew me to the medium in the first place. Let me attempt to answer this with an anecdote. After photographing the skull collection, I came back to the museum with a small print of the “stitched” panorama and asked the head of the Anthropology department: what were the doors in the middle of the cabinet? I considered the doors as a mere visual interference in my photograph. She opened the doors to show me: behind the middle door was the historical photo laboratory of the department, and behind the narrower doors on both sides were boxes with hundreds of glass-plate negatives of anthropometric research. As the chemical photo laboratory is no longer needed nowadays, they recently installed the rest of their photographic collection in that room. This discovery provided a crucial key for my understanding of the collection, and the role of photography in this project; in a way, the thousands of photographs of living people, captured as biological specimen through systematic procedures, are housed within a collection of human skulls that were originally gathered there by the same scientific rationales. Although the photographs of the living showed their faces, and sometimes something of an environment, they simultaneously omitted the very element that was missing from the skulls—the human story. They too were deprived of their individuality and humanity; they were objectified just as the skulls that surrounded them.

The founder of the anthropology department’s photo laboratory, Josef Wastl was, as other prominent anthropologists have been, an enthusiastic photographer. In 1935, he curated an exhibition about the role of photography in science, for which the Photographic Association in Vienna honored him with the silver medal. As an early loyal member of the Nazi party, Wastl became the head of the department during National Socialism reign in Austria. He conducted ‘racial surveys’ on victims of the war and the holocaust and acquired skulls of murdered Jews and Polish POWs.

It became clear for me that my use of photography in this project could not be taken for granted, or be excused with technical considerations alone. I needed to address photography’s legacy, and define ethical questions for the use of photography in the context of scientific racial research and collections of human remains.

RL: I would say that your work goes beyond what is now defined as a traditional institutional critique-based practice, in the sense that you do not address a specific institution—as is usually the case with these practices—but rather, you expose and utilize an appearance in one institution as an example for a wide phenomenon that is relevant to many. Your intention is to then directly affect the phenomenon through what you call ‘Participatory Critique,’ which involves different stakeholders. Would you agree with this historical reading? How do you situate yourself within this evolution?

TA: Every institution that I can think of is part of a larger system, network, or phenomenon. Some connections are very obvious and transparent; others might be harder to perceive. An anthropological museum in Europe, for example, is obviously part of a phenomenon of similar museums, at least in the West. It is probably a member in some professional networks of scientific museums and anthropological societies, but it also possesses, and depends on, various ties with government, academia, private and public capital, and so on. While it is important to address specific local problems and challenges in specific institutions, one has to remember that these problems are often expressions of deeper and wider processes. Personally, I find it inspiring and motivating to think about a work through a local and specific situation, while also being able to invoke or propel its effects on a larger scale.

‘Participatory Critique’ is one of the concepts I am developing currently through the TRACES project, which is funded by the European Union through its Horizon 2020 program. Together with a “dream team” of top researchers and creative minds from ten European countries, the concept, coined by my colleague, art historian and curator, Suzana Milevska, draws on the title of one of my previous projects Voluntary Participation (2012) (which was done in collaboration with the historian Karin Schneider). In this project, we initiated a process of dialog and research with groups, associations, and organizations of Austrian civil society about their engagement with difficult chapters of their past, specifically their participation in National Socialism. I invited them to collaborate with me on their groups’ photographic portraits. Not all groups accepted the invitation, but for some, the participatory long-term engagement produced meaningful processes and insights pertaining not only to the role of civil society, and its ‘voluntary participation’ in extreme regimes, but also to the processes underlying memory work of collective contentious legacies.

RL: Can you further explain your strategy to effect permanent change within the institution? What is the difference in intention between your project and other hosted interventions in heritage or anthropological museums?

TA: I am one of the developers of TRACES, which contains five multi-disciplinary teams, that we call CCPs – Creative Co-Productions. Each team consists of artists, researchers and hosts of cultural heritage. These CCPs develop creative ways to mediate the contentious heritage to broader publics and to establish sustainable solutions for the problems they address. In order to draw significant conclusions from the work of the CCPs, theorize them, and make these insights publically available, the CCPs will be supported and analyzed by other research teams, the Work Packages (WP) that are based at notable European research institutes. The WPs will address different research foci: ethnographic research on and with the CCPs; development of artistic methods and education programs; relation to museums and collections; and dissemination work. As far as I know it is unprecedented for artistic research to be set up for academic investigation in such a comprehensive and programmed way.

This structure was developed to counter inherent issues with what I call “hosted interventions.” In recent years we see more and more institutions of cultural heritage, such as museums of anthropology or history, public and private archives and collections, community centers, education institutions or memorial sites invite artists to create new artworks based on their encounters with the institutions and the heritage they mediate. The artists are usually invited to visit the collections or stay as a resident artist for a short period of time, usually a few weeks. Think about the sensitive nature of the material they may encounter; its complex history, the different communities affected by it, the fields of knowledge associated with it, the decades of research material produced in its relation—with such little time for research, reflection and production, artists are forced to produce anecdotal, symbolic reactions. These artworks might very well be interesting or provoking, but they risk a superficial engagement with the subject and might not be able to challenge its complex problematics in a sustainable way. Furthermore, it has become common practice to publish open-calls for these residencies, asking for project proposals in advance, which further promotes the superficialization of the artistic practice in this sensitive context. The relationships between the artist and the hosting institution are polarized: the initiator of the engagement is often the host, or a third party in collaboration with the host; the artist is a guest, he or she is granted access, they are let-in by the ‘owner’ or the custodian. The artists usually receive payment from the institution, and are expected to deliver their ‘intervention’ within a predetermined period of time. After the delivery of the intervention, the relationship usually ends. These clear and unchallenged relationships reflect positions that might limit further the scope of the artwork. The intervention itself, be it a sticker on a vitrine, a performance, a guided tour or an installation, is usually temporary; at the end of the evening or the festival or the exhibition, it is removed, leaving the space and the subject it referred to unchanged. It did not provide a significant, sustainable change. So, in spite of the significant resources and intentions invested in such engagements, their prospects of generating a sustainable process of change are not great.

One of the ways in which we propose to tackle these shortcomings is through the establishment of the CCPs in which the institution, the artists, and scientists work together over a longer period and share the same budget. They are expected to manage the budget and to design the research and artistic production in a mutual process of discussion, negotiation and consent.

However, this structure poses great challenges for the CCPs: it’s not easy or natural for artists to share their artistic process and it might be difficult as well for researchers to participate in collaborative research in which their usual methodologies are challenged or altered. It might be extremely difficult for cultural heritage institutions to open up, let go of the privilege of power and ownership and accept an equal co-production and a possibility of sustainable change. I’m very curious to see how this big experiment develops over the next three years.

RL: Can you trace your own evolution as an artist that brought you to this practice? What projects led to your current work?

TA: Initially I was attracted to photography and film for their capacity for documenting and representing social realities. I was excited to discover that photography enabled me to approach people and social phenomena that I was curious about, but never dared or knew how to approach. With the camera and the excuse of a “project” I could suddenly engage with strangers, enter their private spheres, discuss with and learn from them. While studying in different art institutions, I explored a broad spectrum of documentary approaches. Though, pretty soon after, and with the development of a more coherent political understanding and stance, I began exploring different ways that my work can interfere and influence the social realities I was relating to. In a way, a shift has been made in my priorities and the way I was constructing new projects: rather than a photographer interested in people, I slowly turned into an artist-activist and researcher who uses photography and other creative means according to strategy and specific project needs.

So in a way, this reflexive process you describe as looking at the legacy of photography first and then applying these questions to other disciplines happened to me in reverse. In 2003 I began working on Unrecognized. This project engaged with communities of the unrecognized Bedouin villages in the Negev, the southern region of Israel, and their difficult stories.1 My introduction to this topic and my decision to engage in a long-term project focusing on it, didn’t initiate with a photographic attraction. Rather, it developed as part of being politically active and in a network of civil and human rights circles. My research and first phases of constructing the project conceptually concentrated on the historical, social, economic and political circumstances of the unrecognized villages in the Negev and the Arab citizens in Israel in general. While looking at the history of colonialism and orientalism, it became clear to me that the way the Bedouin in the Negev were seen and represented by the European Jews who came to create a new state there had direct consequences on the lives of those people whom I was about to work with.2 This posed great challenges to my position in relation to the Bedouin, and my use of photography as a representational medium, as photographer, Israeli, of European Jewish descent.

To conclude, looking at photography and its legacy and assuming responsibility for the way I use the medium only occurred as a consequence of researching first the legacies of the situation I was about to intervene with.

RL: You describe your approach as one that follows equally an emotional urgency and a logical path, can you talk about it more?

TA: Let’s take the skull collection as an example. When I first saw it, in 2009, I was so overwhelmed (or shocked) that it took me quite some time to rationalize my emotions. I knew I wanted to research this, but I did not know if, and how, I should photograph it. It took me three years until I actually photographed it, in 2012. It will take six more years of research, development and discussions until the planned exhibition of this photograph, planned for late 2018. The education program planned with this project will probably take place in 2019 and beyond. So yes, the initial trigger is a very strong emotional reaction and a kind of an abstract, wild attraction to the subject. But then, I slow down considerably, in order to rationalize, plan strategies, learn the subject, design a research rationale, get familiarize and involved with stakeholders, invite collaborations, create synergies and construct a well thought program. Dead Images is a process of ten years, so in some ways, at least in respect to its duration and involvement of scientific partners, it has more in common with scientific research than with typical art production.

RL: How does it relate or differentiate from the way you perceive a scientific practice?

TA: Current contemporary practices allow artists to not only combine and ‘mix and match’ different methodologies, but also to invent new methodologies that suit better the needs of a specific project. In comparison, most scientific practices that I’m aware of are more confined to predefined methodologies, to stricter procedures and rigid standards for research and the dissemination of its results. This is definitely not to say that there’s less creativity in science. I think that good science involves great creativity and as we know from the history of science, many great discoveries and developments were obtained through irregular practices, mistakes or intentionally noncomplying with regulations. Interestingly, often they are described as “inspired moments of revelations,” using similar terminology as in the arts.

With all that in mind, there is still a difference in the way contemporary artists can approach their projects and the amount of freedom they have with choosing the tools, mediums and methodologies compared with scientists from other fields. In my case, I enjoy being able to move more freely between different fields and develop a more creative approach to research methodologies.

TRACES is a three-year project funded in 2016 by the European Commission as part of the Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program. Through an innovative research methodology, TRACES investigates the challenges and opportunities raised when transmitting complex pasts and the role of difficult heritage in contemporary Europe.

- While most of these communities of Arab Bedouin, who are Israeli citizens, can be seen as the indigenous people of the Negev, and most have definitely been living there long before the establishment of the state of Israel, they are regarded by the state as illegal trespassers to ‘state lands’ and their villages are unrecognized by the state. These villages suffer from radical neglect; lack of basic services such as water, health and education; frequent house demolitions and evacuation threats. In this project, alongside a public program of events, I exhibit panoramic photographs of people from the villages, and the stories they told me about the different aspects of living in an unrecognized village.

- I looked at the way the local Negev population was represented in old photographs from the first half of the 20th century, and compared it to the way the new, mainly European settlers were represented. I found two old postcards from roughly the same time: in one, a romantic desert landscape with small distant silhouettes of A Bedouin shepherd and his sheep, on the horizon. In the other postcard another shepherd – a European Jewish ‘pioneer’ with his sheep behind him. He is photographed from a close distance, his body almost filling the frame. These visual representations clearly correlated with the Zionist ideological view of this place and its inhabitants: “A land without a people to a people without a land”. I then chose to work with a wide angle, panoramic format for capturing environmental portraits of the people from the unrecognized villages who tell the stories. I wanted to portray a comprehensive image of the various challenges and struggles that they were facing. At the same time, I wanted to refer to, and challenge, the colonialist way of seeing / not-seeing them with photography. In this project, my portraits try to not romanticize the Negev’s landscape and the Bedouin, and at the same time to refrain from the aesthetization of poverty and neglect. I worked with large format, color film to render a contemporary, detailed, political and respectful panoramic overview of an unfolding civil struggle. What’s more important, the portraits and stories are a result of a participatory work in collaboration with the unrecognized Bedouin villages community representatives. To conclude, looking at photography and its legacy and assuming responsibility for the way I use the medium only occurred as a consequence of researching first the legacies of the situation I was about to intervene with.