Emma Kunz: Visionary Drawings at the Serpentine Galleries

by Claire Phillips

The late Emma Kunz may not have defined herself as an artist or seen her miraculous drawings as anything other than visions of nature, but those are exactly the pieces of the puzzle being placed together at the Serpentine Galleries in London’s Hyde Park. Although it is true that through her powers of divination, the healer predicted her work would be seen by generations to come.

Many might be unfamiliar with Kunz, but her name is often heard in the same breath as the Victorian medium Georgiana Houghton and Swedish mystic Hilma af Klint, now proffered as Europe’s first abstract painter (even before the arrival of her male counterparts Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian). Unlike af Klint, who has become something of a darling of the art world since her own major show at the Serpentine (2015-16), Kunz’s drawings were never meant to line the walls of a gallery, but to lie between her and her patients. Kunz did share her methods in two self-published books The Miracle of Creative Revelation and New Methods of Drawing (1953), but hers was solely an art form by which to live. Kunz barely acknowledged her work should be seen through an artistic lens at all.

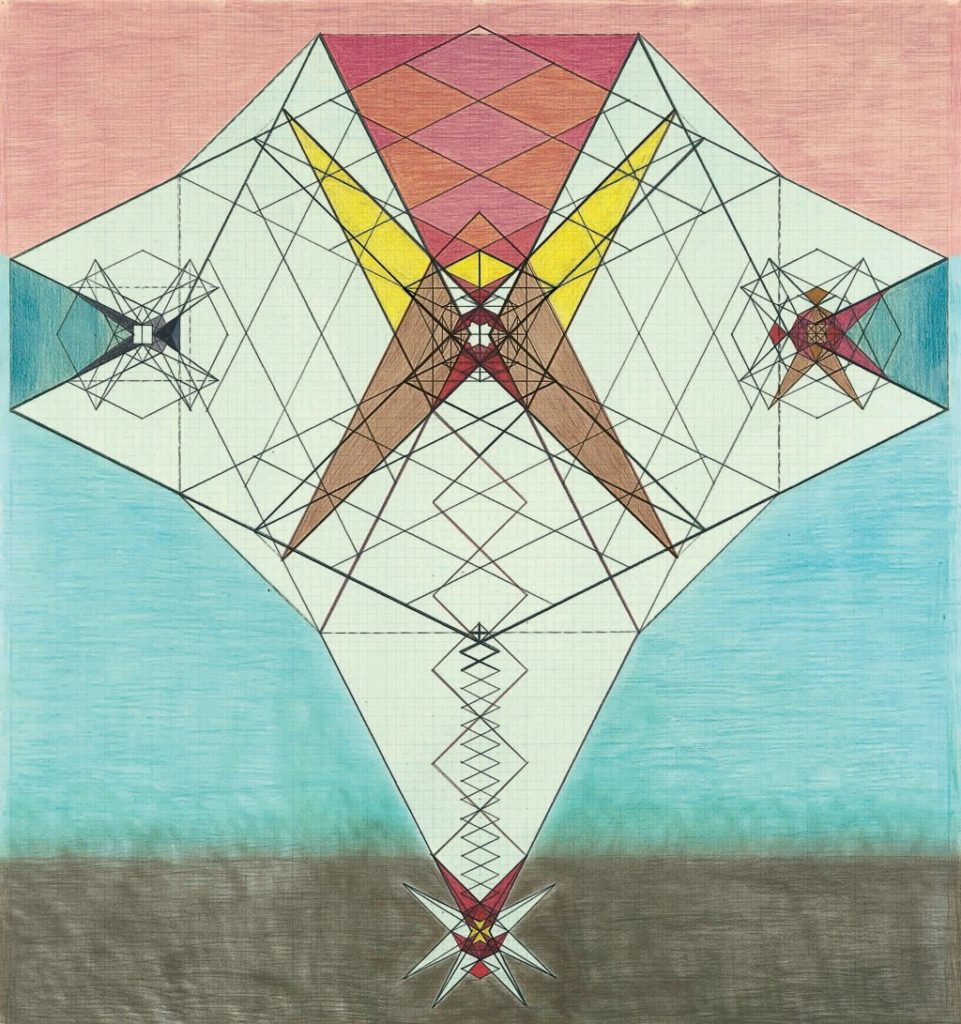

Born in Switzerland in 1892, Kunz realized she had astonishing telepathic abilities and extra-sensory powers at a young age. She filled her school exercise books with drawings of tessellating, geometric designs, the type of which now hang in the galleries of the Serpentine. Kunz explained that these images were in fact a new perspective on the natural world: micro- and macro-visions that encompassed the tiniest and most vast details of the cosmos.

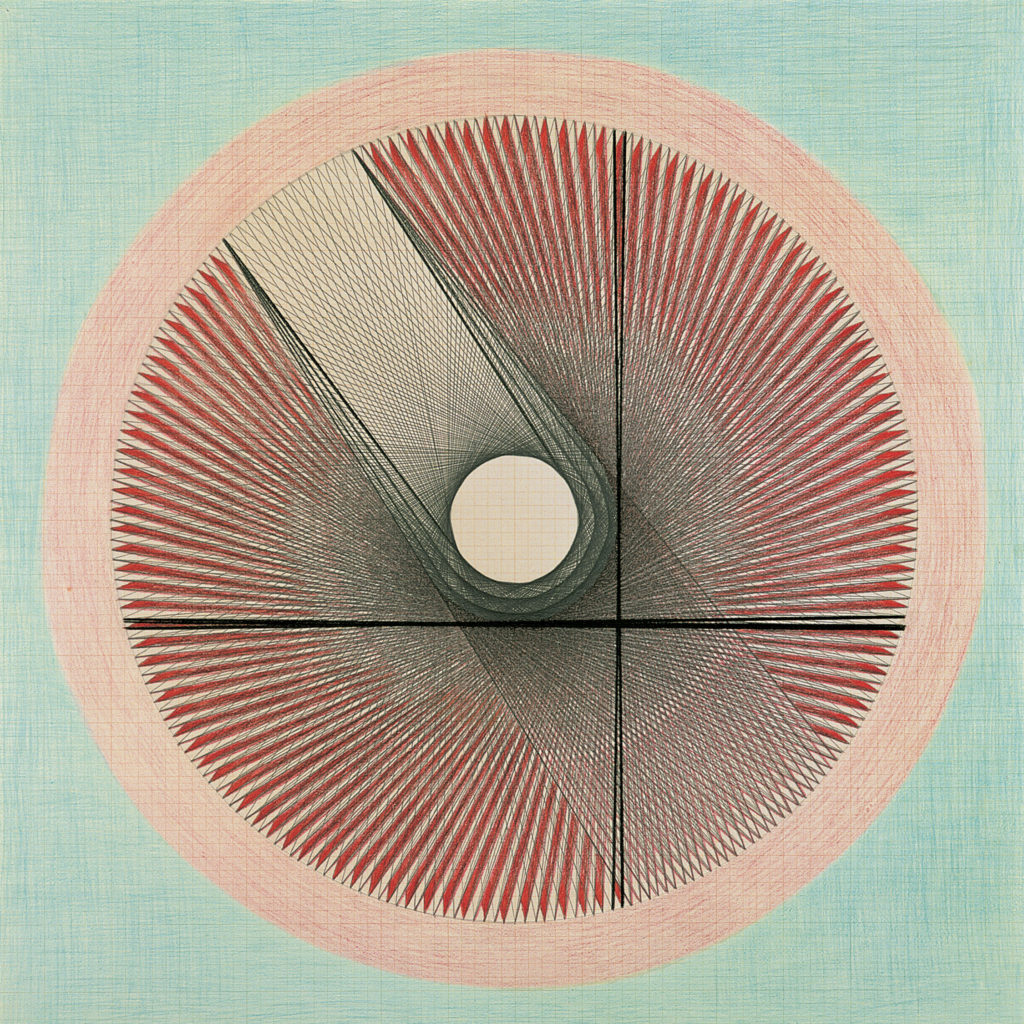

As she grew older, Kunz used her skills as a draftsman in her practice as a holistic healer to guide her remedies. By 1938, now in her forties, Kunz was drawing on a greater scale and using a swinging pendulum in a process called radiesthesia to provide the movements of her hand across the page. The marvelous patterns that appeared, sometimes taking an entire day to complete, are riddled with different resonances and meanings decided by the thickness of their lines, colors and shapes, of which Kunz was the only interpreter. Having grown up in a family of weavers, it is hardly surprising that Kunz was able to pull together these varying threads, acknowledging how each fiber would reverberate against another.

It was the powers that be in the 1970s that first decided to show Kunz’s energy-field drawings in a gallery context, beginning with the Aargauer Kunsthaus Aarau (1973) and later the Musée d’art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (1976), before the celebrated curator Harald Szeemann propelled her legacy to a new stratosphere.

Standing in front of these drawings in the Serpentine it is easy to imagine Kunz looking back at her own work with a similar sense of wonder, astonished by the results. Of course, Kunz never noted down the meaning of these drawings, leaving their muffled secrets entirely up to the imagination of visitors strolling through the galleries.

The bright spaces and the atmosphere of quiet reflection of the Serpentine add to the sense that through Kunz’s drawings, visitors are convening with a higher celestial power. The central gallery—with its towering dome—echoes the architecture of a church and encourages viewers to connect with their spiritual side, to see these images as more than just their aesthetic value. Much like Kunz’s work as a healer, this exhibition recharges visitor’s minds, bodies and souls. Although the drawings appear to be grounded in mathematics, symmetry and geometry, Kunz would have balked at the idea; even worse if she had heard them compared to anything resembling Minimalism. Something of the occult lies hidden beneath their rhythmic, mesmeric lines, which Kunz defined as “the pictorial power of nature.”1 The closest way to understand these mysterious images, which radiate unfathomable energy, is to think of invisible electromagnetic fields and the automatic drawings of André Breton and the Surrealists, driven by unconscious desires and primal urges. Kunz was similarly compelled by impulses beyond her conscious control, yet inspired by the natural world.

Few stories of these curious drawings are defined. One is Work No. 020 (1939), in which Kunz apparently predicted the atomic bomb. The other is the final drawing she made, Work No. 190 (1963), which foretold her death from cancer the same year. Kunz faced the pendulum with similarly burning questions of politics, philosophy and the fate of humanity. In 1942, as World War Two raged across Europe, she was hired by the financial advisor to the royal family of Lichtenstein to “repolarize” Adolf Hitler and set him on a different trajectory. At first, Kunz declined, citing the overwhelming negative energies surrounding the German Chancellor. When she finally conceded, the 63-centimeter metal spring transmitter of her pendulum slashed her body as it flew across the room.

Outside of her abilities as a soothsayer, Kunz boasted eerie powers over nature, like growing a harvest of marigolds, each with multiple flower heads. In the presence of large trees, Kunz would even remove her shoes to feel the streams of energy coursing through the earth beneath her. Kunz’s other notable contribution to the field of holistic medicine was the discovery of the AION A rock in a Swiss quarry, which is still sold today for its healing properties, targeting anything from muscular pain to skin complaints. Seizing the opportunity, the Serpentine holds its own supply of AION A-based cures available from the gift shop.

From Szeemann to Serpentine’s Curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, who would visit the AION A quarry as a child, Kunz has acquired a stream of illustrious fans. Within the exhibition, one such follower, artist Christodoulos Panayiotou, used Kunz’s healing stone to create a series of benches that invite the viewer to take a pew and lose themselves in her vision of the world. But herein lies the problem with making Kunz a figurehead of spiritual and outsider art.

Much like the art world’s embrace of Hilma af Klint, it would be all too easy to fetishize Kunz, who has been appropriated in various ways through the 20th and 21st centuries to fit the canons of art history, theosophy, and anthropology. We should be wary of seeking to understand Kunz too thoroughly or trying to categorize and contain her, moving to quash the inexplicable sense of mystery that surrounds her. That way lies art consultants and their collectors, the insatiable art market and madness. A far better course of action is to surrender to the beauty and spiritual nourishment of Kunz’s work without question or hesitation. That’s certainly how she would have wanted it. Serpentine negotiates the fragility of her legacy with care, but we should fear for the future and what dangers may lie ahead for lesser-known female artists like Kunz emerging onto the main stage of popular recognition and esteem for the first time.

Emma Kunz – Visionary Drawings ran at the Serpentine Galleries from May 19, 2019.