Exit Strategy: Huong Ngo’s Escape in the Time of Pandemic

by Noah Hanna

In 2002, The United States Department of Homeland Security launched the Ready.gov campaign as a means to promote public emergency preparedness in the wake of 9/11. The website as it stands provides resources, checklists, and protocol for over thirty man-made and natural disasters; from the common—such as extreme temperatures, house fires, and flooding—to the unfathomable—threats of nuclear fallout, space weather, and mass violence. There is a peculiar feeling when exploring these pages, a sort of existentialism that arises not from the possibility of these events occurring, but from the nature in which these disasters enter common understanding. The threat of disaster is often a response to its previous manifestation. While temperatures fluctuate to dangerous levels, and storms ravage coastlines in a reality we can comprehend, Ready.gov’s most unimaginable threats can be read more as documents of geopolitical moments. A recording of the fears that plagued a generation or political administration.

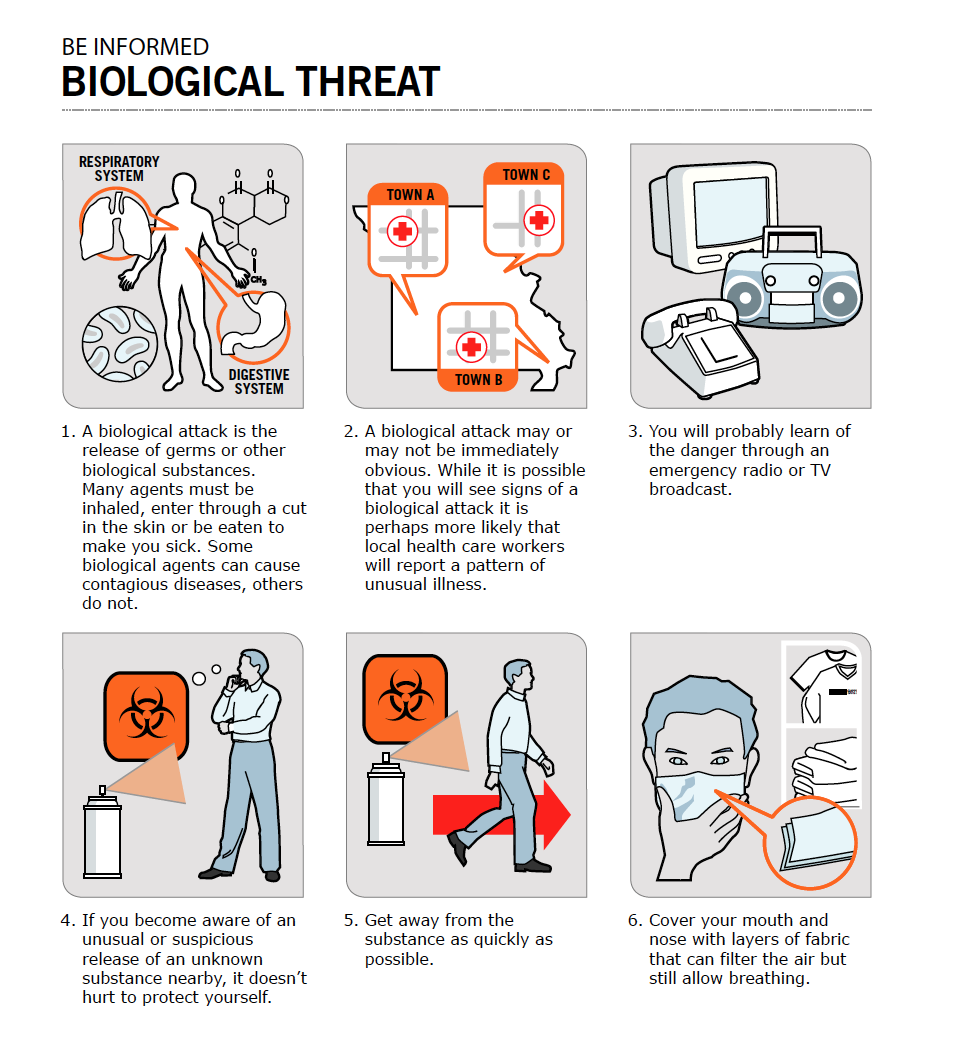

Among the earliest pages to appear on Ready.gov were preparation guides in the event of a biological or chemical attack. In hindsight, no disaster would have been a better fit for this online resource’s launch. Despite the fresh memory of 9/11, American policy had moved quickly onto new threats from the Middle East—the fear of advanced chemical weapons in the hands of a ruthless dictator seemed to serve as enough of a justification for invasion and the need for public resources like Ready.gov. But, like the violent and ceaseless conflict to follow, reality and political narrative quickly amalgamated into the cacophony of psychological half-truths and feeble rationales, rendering both the Invasion of Iraq and a sense of American preparedness alike historically gratuitous.

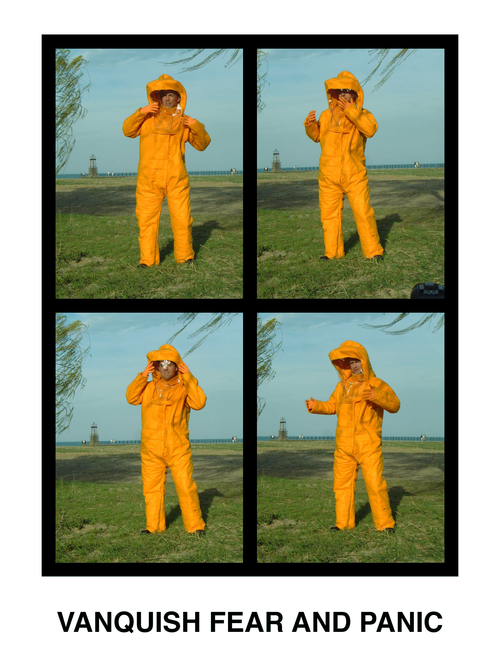

In response to the campaign, artist Huong Ngo (American, b. Hong Kong, 1979) developed Escape (2004, a multifaceted series whose objective was to parse anxiety from fact and investigate the psychology of fear in the advancement of aggressive national defense policy. Mimicking the suggestions of Ready.gov in the event of a biological or chemical attack, Ngo fabricated makeshift personal protective equipment (PPEs), including “escape pods” which could be quickly deployed into wearable protective clothing, informational texts and posters meant to serve as comforting propaganda for an anxious public, and videos instructing the proper application of these items in everyday life.

Common throughout these works and gestures is the overlying desire to escape, both physically and emotionally. Government mandates in the event of an attack which call for the sealing of windows, fleeing of hot zones, and abandoning media communication, reveal a reality in which removing oneself from society as quickly and completely as possible is the ultimate objective. However, with no tangible threat such actions became solely gestures of psychological insentience; directionless and easily malleable.

It was such a state that concerned Ngo at the onset of the Iraq war. A willing or at least compliant public would accept the federal actions to come. Unbridled surveillance under the Patriot act and xenophobia in the name of jingoistic camaraderie became byproducts of post-9/11 America. For Ngo, these policies represented a step towards conceptual social distancing, as Americans increasingly rejected social cohesion and trust in favor of tribe security and technology driven communication. In these isolated chambers, groups were free to radicalize, reinvigorating violent fringe ideologies in favor of challenging the structural systems that had allowed such conflicts to arise in the first place.

While much of the authoritarian and racist national policy that drove Ngo to make Escape in the early 2000s has accelerated tenfold in our current political climate, the project’s applicability to the COVID-19 pandemic goes without saying. For Ngo, renegotiating Escape within the confines of an actual and non-fabricated crisis is a challenge, one that requires a deep examination of semiotics and societal structures. Shortly after speaking with Ngo, the artist was quick to point out the evocation of the common language of war in response to the pandemic.

“It was bizarre to me […] that I woke up one morning that many country leaders were calling this pandemic a war! As if the collapsing of language was necessary in order for us to pay attention—or alternatively to not pay attention to drastic measures they needed to take.”—Huong Ngo

The language of war is the lifeblood of presidential leaders—it is an execution upon an emblematic stage, often serving as the single most critical aspect of forming one’s legacy; a type of immortality. A desire to place oneself among Lincoln and Churchill is what has driven Western leaders to consistently fall back on this lexicon from the decks of aircraft carriers, boardrooms, and executive chambers. It is no coincidence that the scale and reality of this crisis seemed to only hit the Trump administration once the language of war could be evoked and properly molded to demagogic sensibilities. A wartime leader is thought to be omnipotent and unfailing, locking down borders and brashly dispatching enemies for the protection of the nation state—an appealing hat for authoritarians around the world to wear. Yet despite these proclamations of bravery, unity, and strength, the language of war is so often one of precarity: one meant to shield insecurities and propose quick solutions to impossible circumstances. The desire for the war in Iraq to come to a symbolic end, resulting in numerous false starts as the United States consistently disregarded the challenges that Iraqis would face in a post-Hussain society. By declaring a free democratic Iraq, and the end of combat operations, Americans could escape the reality that mounting evidence pointed to a misguided conflict with no exit strategy. In this same regard, Trump’s penchant for self-preservation and disregard for medical science has continued to shift American discourse away from health, and back towards the false narratives and enemies that have defined his ethos.

There is a ubiquitous malleability to language that adapts quickly and unconsciously. Within weeks our lexicon has absorbed a peculiar mixture of technological and medical “artspeak.” We Zoom, wear N95s, and “flatten the curve,” yet warspeak remains a reliable comfort. Its presence in this moment of pestilence will not be revered in the future. Rather, like the work Ngo puts forward in Escape, it will be seen as such: an easy alternative to the immense challenge of global cooperation in the face of a crisis. The race to eradicate a virus is not a war, it is quintessentially antiwar. Military and economic conflicts must be abandoned, barriers to information lifted, and populations must understand that one’s health is directly related to the wellbeing of their neighbors, whether next door or across political, racial, or economic borders. In acknowledging these realities, populations can begin to comprehend that healing and progress comes only from communal efforts, even when congregations cannot be formed.

That being said, abandoning the semiotics of conflict and division only reveals the necessary and substantially more difficult work ahead. As much as Escape exists as a critique on isolationism, it also exposes a statement on the delineation of labor and the tenants of individualism. The hazmat suits and ephemera of Escape are extensions of one’s own design. These items, like any art object, are entirely individualistic endeavors, meant to protect the maker and wearer alone. A concise symbol of American self-determination and hard work. But no labor exists in America outside the tendrils of history. This pandemic has brought the incessant American conflict between the individual and the collective, the public and the private into a reality no longer hidden behind capital production. Private citizens and financial ventures pull this crisis in multiple directions—for better or worse. Ngo discusses this within the framework of PPE, the chief commodity of the modern crisis. The production and distribution of protective face masks provides an unequivocal resemblance to the reality put forward in Escape. As much as we admire and appreciate the individuals who have sewn or printed thousands of masks for their community, we are forced to reckon with the reality in which such actions must be taken.

In much of her practice, Ngo has referred to the writings of theorist Naomi Klein. Klein’s writing on disaster capitalism, or the extortion of disasters and collective fear to push unethical or illegal policies, formed a substantial critique of the Iraq War and she has continued to reference such practices in action today.1 For Klein, the pandemic has reinforced existing hyper capitalist structures. By configuring the work of DIY aid workers as “singularly heroic,” rather than as part of a collective effort or as necessary to support neglected health and service sectors, the United States has continued to deflect accountability, argue against economic and medical welfare, and blame the marginalized and poor for their own misfortune. America has formed a crisis of individual identity that it has long festered deeply in its very soul, idealizing individuality while simultaneously quashing the means to achieve it. The patriots who became preppers and citizen soldiers during the Invasion of Iraq, felt they were continuing the long American tradition of the “Minuteman or rebel” fiercely skeptical of authority and ready for to protect their property and livelihoods at a moment’s notice. Even as the falsities of the war sets in, this ideology prevails; validated as perceived victims of the Obama presidency, and rewarded under Trump. The return of this presence—as freedom-seeking militia in the wake of mass illness—forces us to consider the roots of American ‘freedoms,’ which continue to side with the privileged and economically beneficial, seeking the fastest escape towards an arbitrary freedom.

Similarly, Paul B. Preciado’s essay “Learning from the Virus” published in Artforum, which has no doubt become foundational in the canon of pandemic critical theory, considers this crisis from the perspective of Foucauldian biopolitics. For Foucault, the body is inextricably tied to its political action and that society has transitioned from one of autonomous sovereignty to a disciplinary society in which the body is monitored, preserved, and disposed of based on national interest. Preciado presents this transition through the lens of virology, demonstrating the ways in which plagues have served to reaffirm societal structures and knowledge, and expel those “deimmunized;” whether foreigners or social outcasts. Under COVID-19, Preciado now sees the potential of even greater segregation of the immunized elite and vulnerable working class in a hyper technological and capitalist framework. While well intended for the prevention of infection, mass quarantines, tracking technology, and online labor are easily corrupted for capital and geopolitical gain. Like Ngo and Klein, Preciado sees healing as an abandonment of structural collectivism in favor organic communities and mutual commitment;

‘Healing as a society would mean inventing a new community beyond the identity and border politics with which we have produced sovereignty until now, but also beyond the reduction of life to cybernetic biosurveillance. To stay alive, to maintain life as a planet, in the face of the virus, but also in the face of the effects of centuries of ecological and cultural destruction, means implementing new structural forms of global cooperation. Just as the virus mutates, if we want to resist submission, we must also mutate.’2

Of late, I have struggled with such statements, fearing that the same potential that calls for global community—even when viable and warranted—is potentially equally escapist as nationalistic isolationism. That in our efforts to come together, we have mutually agreed to indulge in a utopian fantasy—ignoring those who cannot afford to leave reality, or otherwise perceiving this faction as belonging to the faceless masses for whom the intellectual elite will safely deliver a state of social equity.

This crisis has proven that the world is broken, from its health systems, to its cultural institutions, and that the burden of capital production, wealth inequality, and structural discrimination can no longer be supported by the populations that must bear it. However, to propose that solutions lie solely in the implementation of alternative socioeconomic or political ideologies is to escape the reality we currently inhabit and disregard the mutual collectivism found within individual pursuits. In our desire to escape, to seek protection from crisis and disaster, we disregard the actions of our neighbors, those who have offered support and humanity without rationale or obligation. A world in crisis now sees its citizen scientists, crafters, artists, and activists coalescing personal ingenuity into communal action. From our solitary studios and eager minds.