Feel Me?: Iceberg Projects

by Jameson Paige

The problem of representation is perhaps one of art’s most confounding dilemmas—how to convey a body, an experience, a moment? Defining the limits and openings in which representation either successfully depicts or regrettably curtails experience is an ongoing project of negotiation. Representation’s logic inevitably leads to fragmented forms of knowing, which nevertheless retain the entitlement of wholeness. Luckily, other tactics for thinking through embodiment on artistic terms have been developed. Feel Me? at Iceberg Projects mobilizes some of these approaches that are particularly attuned to what curator Sampada Aranke calls, the “tiny space between feeling and knowing.”

Feelings happen in a moment or series of instances. They sometimes charge through to shake us; other times quietly rise like stilled steam in a breezeless room. In the last several decades, much has been written about an affective turn in cultural production and exchanges of capital. One way this effort can be framed is a confrontation with representation’s limits. How do subjectivity and cultural conditions become increasingly contingent, allowing us to think through atmospheres just as much as discrete individuals? By studying the slipperiness of feeling, particularly as it relates to object-making, new opportunities for mapping complexity begin to emerge. In the case of Feel Me?, they appear as a tea-drenched shirt with a likeness to sweat or the illusion of a recently extinguished wick, the candle being a severed outstretched arm. These objects are quiet but potent. Their conversation comes from their ability to convey the relatable intricacies of bodily experience without opening themselves to surveillance or foreclosure.

Chiefly engaging this difficult approach are Xandra Ibarra’s series of Rorschach prints made from menstrual blood, She’s On the Rag//Rorschach Test (2015). Stacked in vertical orientation, they are suggestive of a standing figure. The series, digitally expanded in the oppositely installed video, is a strange bending between a litmus test for abstraction and the most familiar of bodily fluids: blood. This doubling makes me think in two ways at once—it leverages abstraction to find representation, while calling me back to my body through its material quality. In Ibarra’s projected video, Menstrual Rorschach Interpretation (2015), the Rorschachs are gridded out as background images and then shuffle in syncopation as her narration poetically analyzes what a viewer might see in her blood’s folded print. She drives deep into abjection, while contending with desire’s simultaneous ability to liberate and constrain us depending on context.

Featured artists Sadie Barnette and Kristan Kennedy both seem to have a penchant for what has been tossed away. In Untitled (Cans) (2018), Barnette imbues a pile of crushed aluminum cans with shimmering sparkle—the ordinary made magic—while Kennedy’s inclusion of cans on painted linen is pushed even further toward detritus in 4.A.M.W.H.N.U.W.H.R.O.N.D.A.C.R.B.N.I.W.S.N.D.A.G.U.T.R (2013). They are mashed and flattened until they level almost seamlessly with the darkly dyed fabric below. Kennedy’s painting is ambitious but not overly eager. Its surface shows time moving slow, and the fruits of a careful, haptic laboring of material.

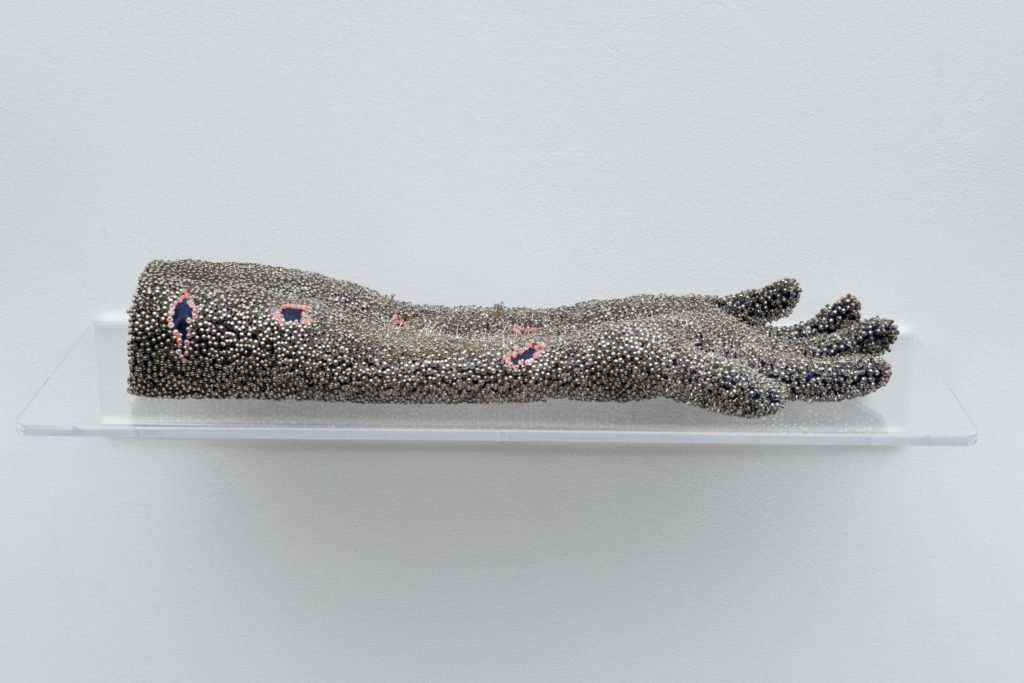

Tina Takemoto’s sculptures from the 1990s invoke abjection a bit more head on. Two outstretched forearms, both entitled Arm’s Length (1995), lie lifelessly on plexi shelves. These arms are lifeless not because of their formal rendering (which is actually quite lifelike) but rather as they appear paralyzed with pain. One is stuck ad infinitum with tiny sewing pins topped with glass beads. It is marked with small sores that open to bright reds and pinks. The other is sculpted from beeswax with several singed candlewicks rising from its surface. Beeswax is among the densest and slowest burning candle waxes, therefore if lit aflame this arm will take excruciatingly long to burn. Both arms seem to grasp at the fragility of making and unmaking our bodies as we move through time; a beautiful accumulation of pinpricks that make up just a single limb of a body’s sensorial schema. These two works engage with the ways flesh can be affected and what healing or pain might look like when translated into material terms—sculpted, melted; calmed, punctured—always carrying the mark of our scars.

The star of this show, Dylan Mira’s 7 Skin Night Repair Essence (2017), hangs still and off-center in the gallery. A drenched t-shirt sags on a retail clothing rack from a single hanger, while latex tubing slowly releases liquid that soaks the shirt and drips into a bucket below. A pump then pulls the liquid from the bucket back into the tubing to drip down again. The circulatory nature of this installation rejects a bodily staining, instead allowing the shirt to press onto itself. Front and back are congealed through the slow spread of the stain. Its perpetual seep through the fabric is earthy, sexy, and releases a scent. The swampiness conjures an image of human sweat sticking skin to fabric on a humid day. However, this closed-circuit system comes off as rather indifferent to viewers. It makes its own sense and moves at its own pace. The staining substance is mugwort mixed with water harvested by Mira near both Los Angeles and Seoul—where the artist lives now and one of the places she grew up, respectively. Mugwort has many different uses depending on where it is harvested from, yet one of its more consistent medicinal properties across cultures is improving gastric and hemic circulation. Mira hints at a body and its need for repair, though the body itself remains absent. Instead, it is a moist ghost.1

Aranke has arranged a constellation of intensities—textures, surfaces, punctures, wounds, scars, residues—that speak to both affective and formal specificity. Yet they have only partially opened the window from which to view. This is a good thing, and an important challenge for viewers to take on. The works assembled here feast on desire’s inability to be sated by leaning towards bodily shapes and processes, while inevitably denying consumption of a known, tangible thing. They seem to be slipping around a corner right as viewers notice their presence, just before meaning fully subsumes form.

Feel Me? runs at Iceberg Projects through October 13, 2019.