Four Decades a Gallerist: Rhona Hoffman

by Katy Donoghue

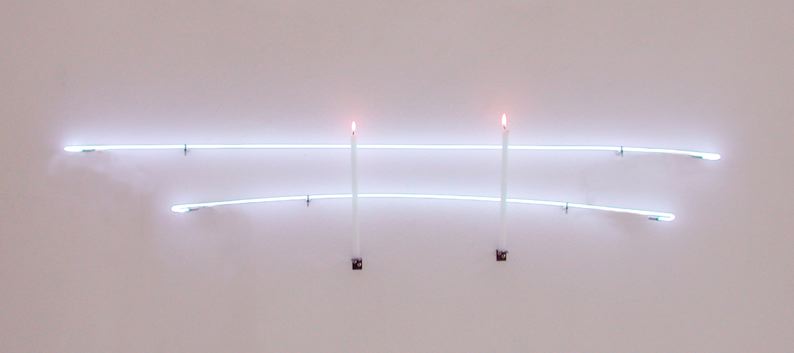

This year marks the fortieth anniversary of Rhona Hoffman Gallery in Chicago. The momentous occasion will be marked with consecutive thematic shows this fall and winter, in three parts—starting in mid-September and running through mid-February, 2017. The first portion of the exhibitions will focus on minimal and conceptual artists previously shown at Rhona Hoffman, such as Mel Bochner, Fred Sandback, Sol LeWitt, Art & Language, and Richard Nonas. The second, looking more at identity and gender, will include work by Natalie Frank, Robert Heinecken, and Luis Gispert. The final, geared towards work that is more social and political, will include Huma Bhabha, Dara Birnbaum, and Leon Golub. Over the summer, while preparing for her suite of anniversary exhibitions, Hoffman was kind enough to sit down with me in her West Loop space. At a table in the back of the gallery we went through exhibition postcards and photos of installations and projects from over the past forty years.

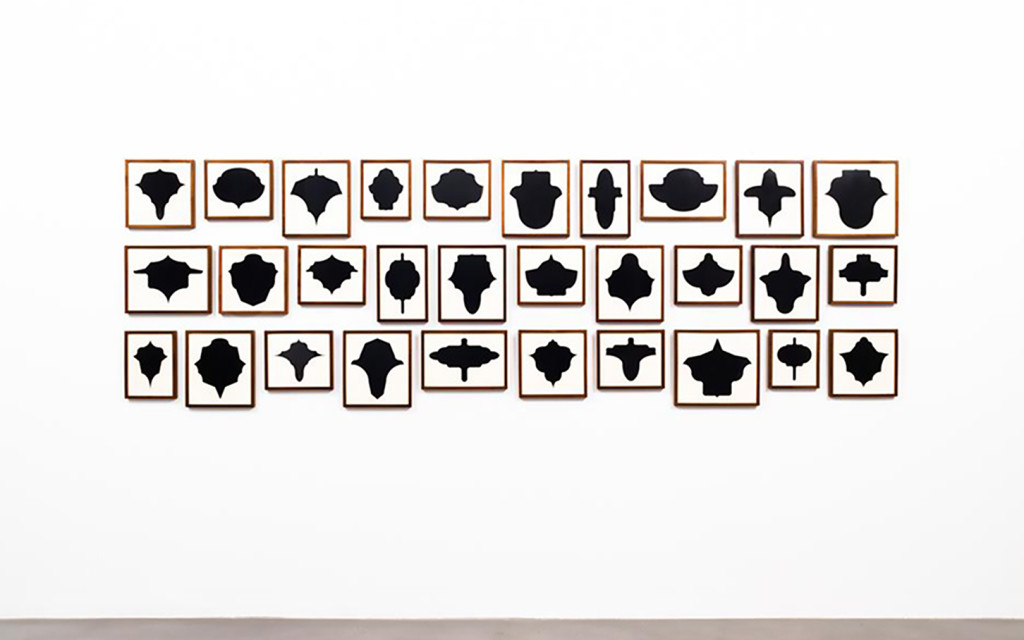

Hoffman moved to Chicago from New York in 1958. She was on the Woman’s Board of both the Art Institute of Chicago and the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) in the sixties, where she stayed until 1974 (she and fellow board member Helyn Goldenberg opened and ran the MCA store during that time). Hoffman and Donald Young opened Young Hoffman Gallery in 1976, first doing shows with Realist and Abstract Expressionist artists, before carving out their own voice in conversations of Minimalism, Conceptualism, and more, with shows that included work by LeWitt, Robert Mangold, Brice Marden, and Robert Ryman. They showed Gordon Matta Clark, Richard Tuttle, Charles Gaines, Gilbert & George, Laurie Anderson, and Vito Acconci all before 1980.

The gallery split in 1983, and Hoffman began working with artists like Barbara Kruger, Cindy Sherman, Dara Birnbaum, Bruce Nauman, Tim Rollins, and Nancy Spero. The nineties brought in shows by Lorna Simpson, Carrie Mae Weems, and Dawoud Bey, among others—and the early 2000s introduced emerging painters such as Kehinde Wiley and Mickalene Thomas. Hoffman continues to look for new talent, such as Derrick Adams, Spencer Finch, Deana Lawson, and Nathaniel Mary Quinn. She has been showing black artists since the first years of the gallery, has shown over 80 female artists over the past four decades, and can be credited with giving many artists their first gallery exhibition.

That Hoffman has represented and put on shows with some of the same artists over several decades—like LeWitt, Matta Clark, Kruger, Sherman, Tuttle, and Acconci—is a testament to the strong friendships she’s forged outside the gallery, as well as the work she has put into both selling and placing art in important collections, institutions, and special projects. Hoffman’s admirable eye and taste extend beyond painting and sculpture to architecture and ceramics, and her knack for spotting ability and potential in young artists has never wavered.

Over a few visits and phone calls in the months leading up to her anniversary shows, Hoffman shared anecdotes and stories that were funny, jaw-dropping, and awe-inspiring. Times certainly have changed—you can’t just look up someone in the phone book and call them for a studio visit anymore—but Hoffman’s instinct and spirit certainly hasn’t.

KATY DONOGHUE: Let’s start at the beginning. Tell me about the first shows you did with Donald Young when you opened the gallery in 1976.

RHONA HOFFMAN: We first did a show on Realism [Oct 8–Nov 10, 1976] and a show on Abstract Expressionism [Around 10th Street, Nov 12–Dec 15, 1976]. With the Realism show we got lucky. There was a man in Detroit who died and whose collection of Realism had really major art figures. We had had got some more from Susan & Lewis Meisel in New York, so we rented a truck in New York, we drove to Detroit, picked up this collection, drove it back to Chicago, and then hung it. In the beginning, we went and got the art, hung it, I cooked dinner, invited people over, washed dishes, went to bed, and then got up and got to work the next day. The art world then was really simpler—it was not very costly; a Joan Mitchell painting was $4,500. Art was for people who were middle class. It was accessible financially. You didn’t have to sell the kids to buy a painting! [Laughs].

KD: Do you remember the first thing you sold?

RH: The first thing we sold was a Larry Rivers out of the back room to Lou Kaplan from Paris. Starting from the get go we were very fortunate. Chicago had another generation of really good collectors like Paul and Camille Oliver-Hoffmann or Mort Neumann. They were wonderful, serious collectors of art that came to the gallery and their taste identified with ours.

The Hoffmanns bought Vito Acconci’s Maze Table (1985). They lived at 209 East Lakeshore—she was really an amazing collector. She knew that they weren’t owners of art, they were trustees for it. She took out all her dining room furniture and the Maze Table became what was in the dining room. Behind it, they also had a Ryman, there was a Kelly, there was a Twombly, and there was a LeWitt on the floor.

KD: What was the next show, after those first two?

RH: A show of prints with Parasol Press that had Agnes Martin, Brice Marden, Robert Mangold—that whole Minimalist group [Jan 8–Feb 16, 1977]. Then we started showing Donad Judd, Vito Acconci, and Sol LeWitt was one of our first shows. Sandback we picked up later.

I have been so fortunate; these are people who really became friends. When you can identify an artwork that you really like in your soul, you probably like the person too. There are lots of things you’re agreeing about, including where to have dinner!

It was different then. You went to the phone book, you picked up the phone, you’d say, “Hello my name is Rhona Hoffman, Donald Young and I would like to visit your studio.” It was easier.

![© [2016] Donald Judd / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York](https://theseenjournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/DJ-PCB-52-PRT-755x1024.jpg)

KD: It’s different now?

RH: I don’t know what the situation is starting out now because now I’m privileged and I can call people.

KD: But you still want to get along with them, I guess.

RH: No, but it is better. Mostly without exception, the art I like comes with people I like. Julian Schnabel and I like each other still, but we did a show. The show was called Ornamental Despair [October 17–November 18, 1980], we did a postcard of the painting he did by the same name (1980), it was black velvet, all white paint, gorgeous. But he didn’t like the size of the postcard; it was too small, so we reprinted it this big [holds her hands a foot apart]. It was done nicely, but it was done for his ego [laughs].

KD: What were some of the big shows for you in the early eighties that you recall?

RH: In 1982 we had a great show of Robert Ryman’s work [March 12–April 13, 1982] that went to dOCUMENTA that year. We also did a big exhibition of Georg Baselitz [May 11 – May 22, 1982], and most people in Chicago didn’t know who he was, so they were startled by the price. We were like, the man is over forty years old, he’s been selling art for years! It was a great exhibit, and we were able to sell two out of the whole show. A year later, the head of the Art Institute called and said, “Do you still have any?” We said we did not.

KD: And then the next year, 1983, you and Donald split the gallery, and you established Rhona Hoffman Gallery.

RH: Yes, so in 1983 Donald and I split our galleries, and you can see by the shows that the Minimal and Conceptual focus continues, but it becomes more socio-politically focused. I show more black artists, more women artists—unconsciously done, of course. This was not a thing where I said, “I’m going to show black or women artists.”

We showed Barbara Kruger. You know that famous work that says, “It’s a small world but not if you have to clean it?” That was in our exhibition [April 6–28, 1990], the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles bought it from us. We did a fun project with Kruger; David Meitus used to own a match factory, so we made Barbara Kruger matches. [Takes out a Ziploc bag full of them to show me] I used to just give them away!

KD: I heard you have a good Leo Castelli story.

RH: I don’t know when it was but it was in the eighties. The Chicago art fair had really become a place to be, and people started realizing that Chicago had really wonderful collectors—the reason I’m still in business is that I figured that out, by the way!

So Leo comes to Chicago for the art fair and at that time I was driving a checker marathon limousine with jump seats that sat twelve comfortably.

KD: I’m sorry, you were driving a limo?

RH: Yes! When I moved into the city after my divorce, a friend of mine, David Markin, owned checker cab! It was maroon with a black top, really funny! It got about twelve miles to the gallon on the open road but it was so superb, I loved it. I remember in 1978 when Gordon Matta Clark was doing the project for the MCA where he cut the building, it was February and Gordon hadn’t seen anything, so myself and Judith Kirshner, who was the curator for the MCA at the time and one of my dear friends, put him in the back of the car and we drove him around Chicago.

But back to Leo, he was in town for the fair and had said he hadn’t seen anything in Chicago. I said, “Oh, come in my limo! I’ll take you for a spin!” [Laughs]. And I was taking him and his wife all over Chicago. At around noon we were in the banking district and I ran out of gas. So there I am, in the middle of the street at noon with no gas with Leo Castelli, a hero of mine and maybe the most famous art dealer in the world, along with his wife. Leo was laughing, so I got out of the car. I was much younger, much cuter, so I went to the back of the car and I put my hands on the trunk. It was lunch time, so all these guys are coming out of the banks, and I’m staring at people on the street, until I caught one! [Laughs]. And now Leo is really laughing, as this guy help pushed us to the side of the street. And then I would never have the nerve to do this, but because it was Leo, I turned off the motor, and I left the car there, and Leo and I and his wife went off.

KD: No!

RH: It was incredible. I mean the nerve! I was trying so desperately to please him. He was someone who really loved women, but he also admired women. He didn’t show very many, maybe Lee Bonticou was it.

KD: Your exhibition history is quite different from that; You’ve shown over 80 female artists, right?

RH: At least. You know, in 1974 when I got divorced, I wanted an American Express card and they wouldn’t give it to me because I was divorced. And I said, “I spent all the money! What are you talking about?” Anyway, I still don’t have an American Express card.

I became more feminist, not just because of that, but there are certain things that happened in the world, and there started to be more and more women artists who were sick of the male gaze and started doing the female gaze. There had always been Nancy Spero, but in the late seventies you started to see Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, Jenny Holzer, Nancy Dwyers, the list is really long.

It was really lovely to have this thing that was in my personal life, and the things that I subscribed to, be part of a conversation in the art world, and to become friends with the artists who shared my feelings. The art world is a fascinating one because it involves all the worlds, including language, literature, movies, so it becomes a way to stay plugged in.

KD: Did you always feel comfortable with your eye?

RH: Yes, for good or bad, or maybe delusional, but yeah I did. I do. If I walk into a room, I know.

You can’t make an eye. You either have one or you don’t. You can improve a bad or mediocre eye. Over time, I’ve begun to respect my eye. There is something that happens when there’s a confluence of your head and your stomach agreeing. And if those two things don’t come together, you really shouldn’t buy it. Your intellect and your emotional situation really have to be in agreement for you to like something enough to buy.

A man was here last week, he showed me something and I asked him, “What more do you want to get from it? There is nothing more for you to see in it, so there is no point in buying that.” You have to buy something where you can keep discovering new things about it, learning something or feeling something. It has to be more complicated.

Rhona Hoffman Gallery will present 40 Years: Part 1 September 16–October 22, 2016; 40 Years: Part 2, October 28–December 23, 2016, and 40 Years: Part 3, January 13 – February 18, 2017.