Framing Fraktur: Word & Image

by Joshua Michael Demaree

The connection between word and image is as old as the need to communicate and commemorate. Certainly the first link was communication: “This image of a deer I drew is, in fact, the deer you killed the other day to feed us all,” thought the first artist. While it is unlikely that the connection was so eloquently put, this basic idea of the link between word and image remains the same today; one can easily step in for the other when the need arises.

Since the time of that first imaginative cave dweller, we have replaced our cave images for words (which are intricate image-systems themselves) and, theorists argue, in the Information Age we have begun to replace our words again for images. This fact is not lost on anyone who deals in words for a living and I imagine it was such a thought that inspired that The Free Library of Philadelphia’s most recent exhibition, Word & Image: Contemporary Artists Connect to Fraktur.

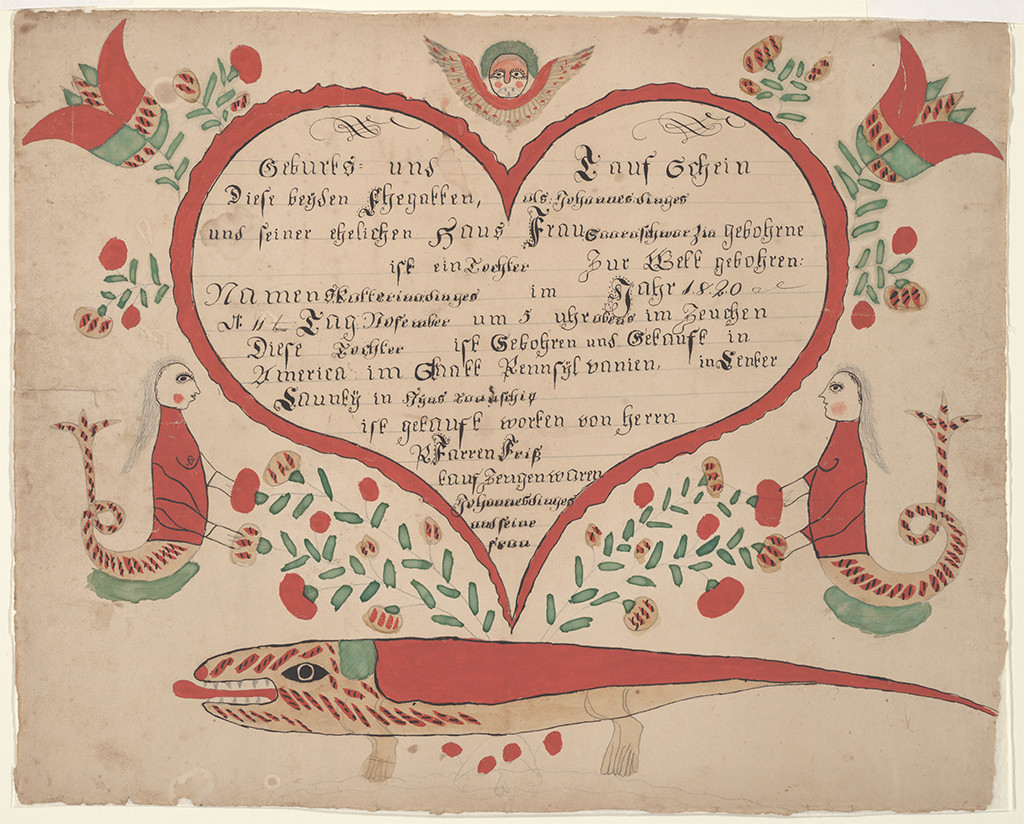

Currently on view at the library’s central branch on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway is one of four exhibitions taking place in the region to coincide with a publication and conference all focused on one thing: fraktur. While the name may be unknown, the sight of fraktur is comfortably familiar to anyone born in the lower two-thirds of Pennsylvania or eastern Ohio. It is historical folk art of the Pennsylvania Germans (more commonly referred to as Pennsylvania Dutch, but this is a misnomer). Fraktur, more specifically in this context, is commemorative drawings or paintings completed for major life events within the Pennsylvania German community during the 18th and 19th centuries. Marriages, graduations, births, new houses: a fraktur meant that you had arrived, it was a precious and personal work of art.

Throughout the long and storied history of the Pennsylvania Germans, fraktur developed into its own sophisticated system of words and images. Often containing both, an example might include a pronouncement (the birth of Maria Xander, for example) and an illuminated marginalia of religious figures, flowers, or birds in a plain-yet-beautiful abstract folk style now more commonly associated with Scandinavia and found plastered en masse on duvets at IKEA.

But the value of fraktur is more than just a Pinteresting bargain bin find, as the collective exhibitions and conference of Framing Fraktur aim to illustrate. The Free Library, not normally the site one would think to visit for thought-provoking contemporary art, has turned its galleries into just that by curating its exhibition towards understanding how the intricacies of fraktur and its vernacular combination of word and image, form and craft exist in the modern artist’s practice.

The exhibition pulls together a group of international artists whose work is situated, much like fraktur itself, in a meaty center between fine arts, design, and craft: Marian Bantjes (Canada), Gert and Uwe Tobias (Germany), Anthony Campuzano (United States), Imran Qureshi (Pakistan), Elain Reichek (United States), and Bob and Robert Smith (United Kingdom).

As you enter the library’s grand lobby, you encounter six large woodcuts from German twins Gert and Uwe Tobias. The works, part of their Die Mapp series, each piece is inspired from a collection of old embroidery patterns, linking text and visual instruction in a massively abstracted assemblage not unlike Moholy-Nagy’s telephone paintings. Researcher Lisa Minardi has found print sources from some of fraktur’s more unusual iconographies: a mermaid from a 1775 London periodical, suggesting these folk artists were (however unconceptually) engaged in forms of appropriation and abstraction long before modern art. The Tobias twin’s work follows this trajectory of appropriation through instruction, recreating and decontextualizing symbols in order to re-codify them.

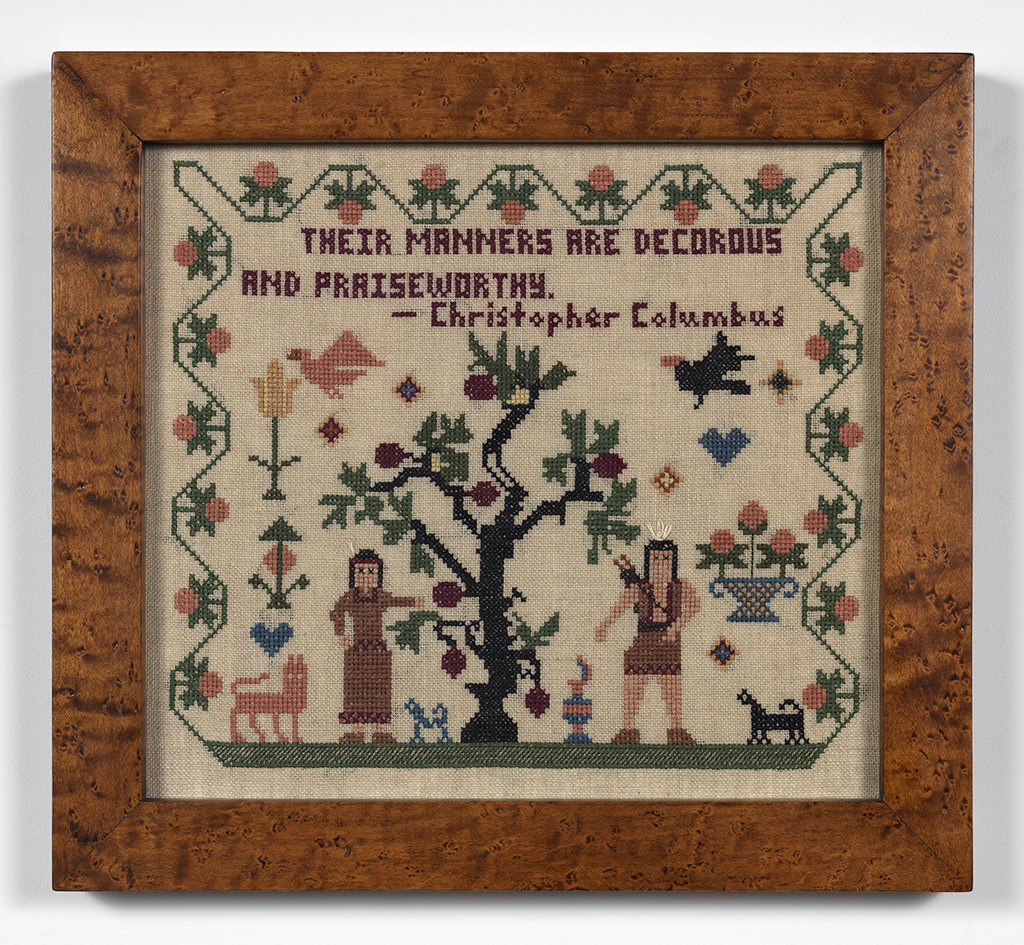

Turning west, you can enter the first floor gallery, which includes two long rows of display cases each with several pieces juxtaposed with images of fraktur for comparison. (The cases lending this gallery more the feeling of an archive than a gallery.) This floor’s most powerful piece comes from American artist Elaine Reichek, whose name is foundational within contemporary fiber and materials studies. Since the 1970’s, she has been working in a conceptually painterly way with thread and embroidering. Fraktur’s many coded motifs, which were traditionally done in paint or ink, were carried across the 19th and into the 20th century through its adaptation to sewing and craft, found now in framed samplers and Mennonite quilting.

On display is Reichek’s Sampler (Their Manners Are Decorous), which adapts the form of a sewing sampler (used to repeat a variety of stitches to display and improve one’s skill) that might typically include Christian scene of Adam and Eve. Reichek’s piece still tells the tale of man’s fall from grace, but she turns from religion to politics, replacing the first Christians with two native Americans and where we might normally find a bible verse in God’s words dispelling the two from Eden, we find a selection from a quote of Christopher Columbus describing the aborigines he found in the new world:

So tractable, so peaceable, are these people that I swear to your Majesties there is not in the world a better nation. They love their neighbors as themselves, and their discourse is ever sweet and gentle, and accompanied with a smile; and though it is true that they are naked, yet their manners are decorous and praiseworthy.

It would, of course, be their peaceable nature that allowed Europeans the ability to spread sexually transmitted infections to the native populations and to enslave them for the mining of gold and other resources. Reichek, who does not shy from exploring untold narratives, makes a powerful statement subtly told through the codified motifs of needlework, combining politics and craft in the earliest throws of third-wave feminism.

Returning to the lobby and walking up the museum’s grand staircase to the upstairs gallery, you can find a hanging carpet from the Tobias twins placed just above a statue of the library’s founder; situated in a field of black is the embroidered image of a skull, a dark twist that marks the humor instilled throughout the show. Perhaps because it is a library (versus museum or gallery) or possibly it is the nature of craft to have a more vernacular appeal, but most pieces in the show read as playful, including two companion sculptures from Bob and Robert Smith (the pseudonym for British artist Patrick Brill) located on the second floor landing.

In the upstairs gallery there are more pieces from each artist, this time hung traditionally. Notable pieces include Philadelphia-based Anthony Campuzano’s Constant Life Crisis (2005) and another sampler from Reichek that uses quotes from Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer. A favorite from this gallery is Canadian artist and typography celebrity Marian Bantjes’ Lost Child (2014). Using the tails from My Little Pony dolls, Bantjes weaves a rainbow-colored tapestry that spells out ‘lost child,’ using craft to insinuate a damning connection between consumerism and marketing towards children.

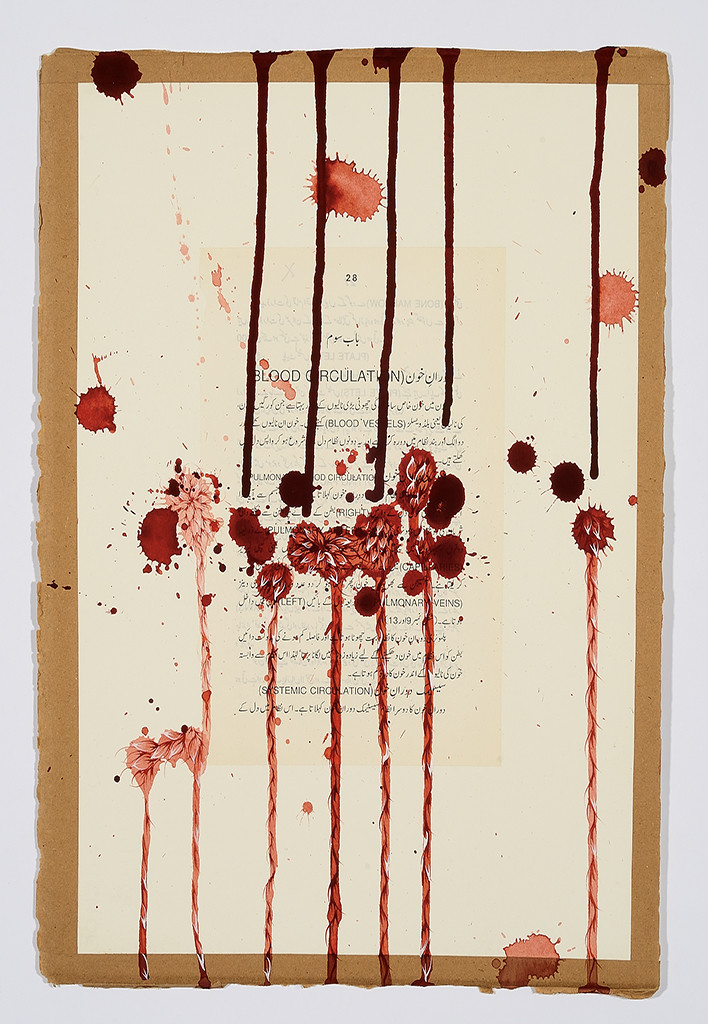

Across from Bantjes is the work of Imran Qureshi, a Pakistani artist whose signature style is to use blood red ink, lending grotesqueness to his beautiful illustrations. On display is his Hard to Understand (2013); a page on heart circulation from a medial textbook becomes the unlikely recipient for illuminated marginalia, turning an otherwise technical text into a bloodsoaked pronouncement of the heart’s emotional mystery in light of its practical functions.

Hung at the far end of the gallery is a quilted banner by Bob and Roberta Smith that reads: Art Makes People Powerful. Created in response to discourses of austerity and despair of conservative politics, the piece is undeniably cheerful in form and empowering in message. The Smiths’ work routinely comments on the politics of artmaking—by painting on everyday objects (i.e. baking pans, headboards, bed sheets), Bob and Robert Smith break down hierarchies of appropriate art practices, further emphasized by their frequent painted messages such as “MoMA is too expensive” and “No One Owns Art.”

Art does in fact give power to the people, the power of expression and the means through which to communicate themselves. This exhibition lays that linkage clear: connecting artists through the art historical concept of fraktur, whose purpose and form, like other folk arts, are inextricably linked. The power of fraktur is in their celebration of the personal and the domestic, a concept found in each of these international artists’ works, and a quality not yet valued outside of an art historical context.

Sure, much contemporary art is personal in some way. The viewer perhaps values this only second to aesthetics—we are always eager to learn something more about the creator. But it is this connection to the personally domestic, not necessarily the same independent concept of the personal we think of today. In Pennsylvania German communities, the individual is unthinkable outside of a communal context. Few cultural groups have remained so steadfast to their communities as the Amish and conservative Mennonites, who have retained their practices of living simply for over two centuries in the face of unprecedented technological change; the person is the family is the community.

It was the connection between the old world and the new world, something the library illustrates particularly well, that drew me to this show. I was also excited to see how alternative spaces can change our reaction to art and, through this change of venue, alter our practiced tendencies to place value in certain ideas more than others. The library is a cozy place, certainly religious in tone like the museum (everyone whispers in both), but whereas the museum is often social, the library is a space for the individual and for reflection. It only seems appropriate that the library would house an exhibition focused on the personal and the domestic, and to show that the concepts inherent to fraktur and folk art as a whole are alive and well in contemporary art.

If I could sum up my reaction to this exhibition in one word, it would be: ☺.

Framing Fraktur runs through June, 2015.