Gramática de las Puertas (A Grammar of Gates): Miguel Fernández de Castro

by Isabel Parkes

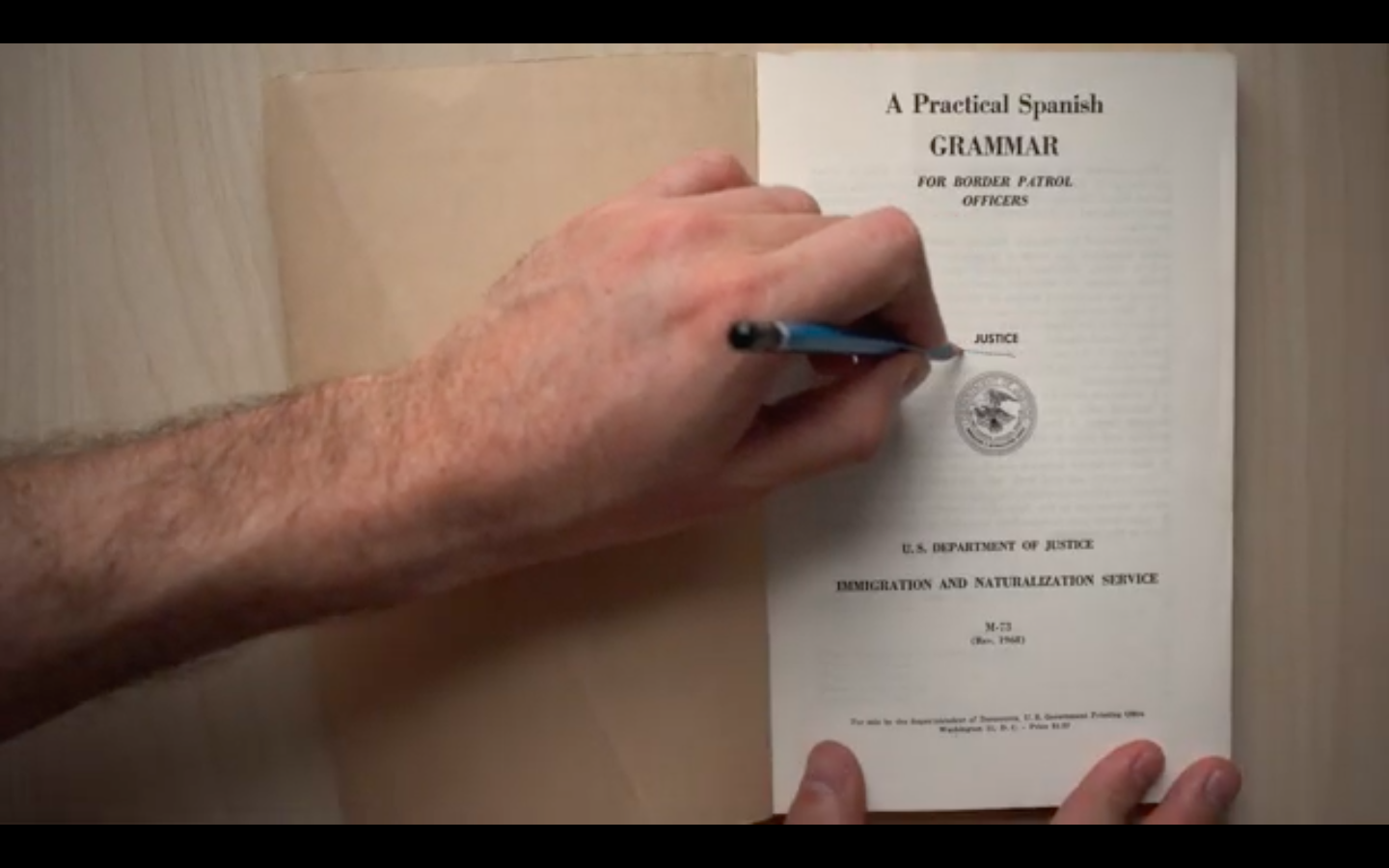

Miguel Fernández de Castro’s 20-minute film, Gramática de las Puertas (A Grammar of Gates, 2019) combines footage of the ancestral territory of the Tohono O’odham Nation, an indigenous people that inhabits the area between Sonora and Arizona, with clips from Geronimo Jones, a 1970 short film set in the same region. De Castro’s main characters are the eponymous young protagonist of Geronimo Jones and a handful of anonymous U.S. Border Patrol Officers who pose in uniforms and flip through a 1968 revision of A Practical Spanish Grammar for Border Patrol Officers. As he does often with his sculptural and photographic interventions, De Castro uses geography and geology to examine the intersections of exploration, exploitation and control in the Mexican-American borderlands. His film poses resonant questions about the relationship between material and invisible, fact and fiction, and past and present, and elucidates how each influences the other.

Early on in A Grammar of Gates, a white hand underlines the word “JUSTICE” on the title page of the instructional booklet. Later, the hand flips to a page of questions for practicing Spanish, which include: “1. What are you doing with this document?,” “6. How many relatives to you have?,” and “22. Why do you always lie?” An emotionless American male voice reads notes on grammar: “The subject of a passive verb receives the action. It does not do anything,” as the young Geronimo hitchhikes through a dusty desert landscape. These and similar scenes follow words in and out of their histories. They make a clear case for how language can be weaponized, as well as how grammatical structures can move off a page and inform how social and political processes occur.

De Castro’s use of the government-issued booklet alongside a film that was originally released by the Learning Corporation of America (an educational division of Columbia Pictures) presents disturbing and historically overlooked references that point to the ongoing violence that afflicts indigenous people who inhabit this region. In one string of scenes, Geronimo’s cousin, an astronomer, brings the boy to “look at the sun.” The affectless voice recites, “This has been an observatory of the National Science Foundation since 1958,” then the same phrase in Spanish spoken with a thick American accent, as Geronimo gazes through a fence at a graveyard marked densely with homemade wooden crosses. The observatory is Kitt Peak National Observatory, located on Kitt Peak or loligam, a sacred mountain of the Tohono O’odham.

The cursory origin story of Kitt Peak Observatory, found on the website of the association which operates it on behalf of the National Science Foundation, reads: “When the tribal council of the Tohono O’odham Nation was first approached with the plan to build an observatory on their sacred mountain, they refused. However, a solution was achieved.”1 In A Grammar of Gates, a scene shows footage of southwestern desert flora and fauna as the now-familiar voice states, “The observatory produces scientific knowledge,” followed by the phrase in Spanish. De Castro juxtaposes grammatical rules and examples of their implementation with quotes and imagery that highlight how the U.S. government legalizes structures that render indigenous peoples passive, and how this position is reiterated in popular media.2 In speech (the booklet) and in policy (the decision to build on a sacred site), the Kitt Peak Observatory—a Trojan horse erected at the start of the space race and today geographically key for the U.S. Department of Customs and Border Protection—remains active.

A Grammar of Gates also marks the artificial line between systems of surveillance and celestial as well as physical bodies. It redirects our attention to the diverse ways spaces are occupied and walls formed, at a time when the U.S. government is increasing its ability to virtually monitor exactly this area.3 At times the film struggles to balance its blend of sources, moving rapidly through the artist’s own imagery and slowly through Geronimo Jones. This has the effect of watering down De Castro’s own ideas or rendering them didactic, an impression reinforced by moments of overt symbolism – a bull’s carcass being dragged through dirt or a burning Saguaro that resembles a body with arms raised in surrender. While strong themselves, these images distract from the simple, semantic cleverness of his initial strategy to link original and found footage.

Nevertheless, De Castro offers a timely and original reading of an ongoing conflict that too-often emphasizes a single point of view and risks disempowering indigenous people by portraying them simply as victims. Rather than foregrounding only the perspective of the Tohono O’odham, De Castro employs American legal and linguistic frameworks alongside media and surveillance imagery to expose the militarization of sight and speech lines which extend between imagination and experience. At a moment in which a virus that ignores borders has us waiting to be free from the constraints of lockdown, A Grammar of Gates focuses our attention on limits that still need to be contested.

Gramática de las Puertas (A Grammar of Gates) streamed on the Whitechapel Gallery’s website from April 15 extended through June 9, 2020 as part of Artists’ Film International, a collaborative project featuring film, video and animation from artists around the world.

- Author’s Note: The Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, aka AURA, was founded in 1957; “Kitt peak National Observatory: Tohono O’odham.” National Optical Astronomy Observatory. No publication date. Accessed May 8 2020. https://www.noao.edu/outreach/kptour/kpno_tohono.html

- Author’s Note: At the start of Geronimo Jones, the young Geronimo (Martin Soto) receives a turquoise amulet from his grandfather. Wanting to buy a birthday present for his grandfather (Chief Geronimo Kuth Le), Geronimo trades the talisman for a television, which he brings home and places before him. Turning it on, grandfather and grandson are confronted with various scenes that depict Hollywood battles between “Cowboys and Indians.” Visibly uncomfortable, the grandfather closes his eyes. The boy turns off the television. The film is available on YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-0luCjgrt5c

- As reported by various sources, “in March 2019, the Tohono O’odham Legislative Council passed a resolution allowing U.S. Customs and Border Protection aka CBP to contract the Israeli company Elbit Systems to build 10 integrated fixed towers, or IFTs, on their land, surveillance infrastructure that many on the reservation see as a high-tech occupation.” Todd Miller, “How Border Patrol Occupied the Tohono O’odham Nation,” In These Times. June 19, 2019. Accessed May 8 2020. http://inthesetimes.com/article/21903/us-mexico-border-surveillance-tohono-oodham-nation-border-patrol