Hayv Kahraman: Acts of Reparation // CAM St. Louis

by Annette LePique

In Acts of Reparation, the intimacy of Hayv Kahraman’s female bodies foster a space in which Kahraman unites her memories, resistance, and trauma with those of a collective female experience under a postcolonial state. Curated by Wassan Al-Khudhairi, and currently showing at the Contemporary Art Museum of Saint Louis, the works in Reparation are formed through Kahraman’s tangible reconfiguration of her own forced migration and experiences as an Iraqi immigrant. As a young girl, Kahraman and her family fled their Baghdad home for Sweden during the first Gulf War. In her essay “Collective Performance: Gendering Memories of Iraq”, Kahraman considers how this permeation of neo-colonial wartime violence within her childhood memories created a psychic schism that still remains in her life as a visceral, tangible presence. This investigation of Kahraman’s trauma merges with that of the collective as her unnamed female protagonists float and shift throughout the exhibition; their bodies confrontational and pierced against a landscape of memory. The idea of setting is crucial to Reparation as Kahraman’s minimalistic environments function as signifiers of her Iraqi childhood and maps from which she navigates the disruptions of Muslim and female identities.

Though Kahraman probes the loss and absence inherent to colonial violence, the lineage of her work is not solely defined through trauma. Such a distinction is crucial to remember as it is problematic to define the stories of those who have resisted oppression through the schema of the oppressor. Pieces included in Reparation were chosen from various sets of Kahraman’s work: Audible Inaudible, How Iraqi are you?, Let the Guest be the Master, Pins and Needles, all of which were created during the last ten years. While the pieces chosen do not, nor wish to, form a linear timeline they all examine how bodies survive and change under the weight of memory. Though the bodies of the women featured in each piece differ in how they interact with their environments, some fade into a diaphanous mist while others urgently spill from the canvas, all subvert viewer expectations of how female bodies should behave.

Such subversion stems from an ambiguity of corporeal borders; Kahraman’s figures are living, breathing ghosts. They are women in possession of an agency borne of indeterminacy, they are between two worlds. Kahraman’s experimentation with this conception of the indeterminate is informed through Homi K Bhabha’s theory of the Third Space. In Bhabha’s essay “Cultural Diversity and Cultural Differences”, he quotes Algerian writer and philosopher Frantz Fanon’s conception of the location of culture as “the zone of occult instability where the people dwell.” From Fanon, Bhabha conceives of a liminal space where those oppressed and disenfranchised create new modes of culture informed by both their origins and the unknown of revolution. This dichotomy between new and old in turn manifests a hybrid state where agents simultaneously exist within and beyond borders. Though criticisms have been levied at Bhabha for essentializing the third space and not adequately distinguishing the spatial contexts in which it may appear (i.e., first world nations compared to third world nations), Kahraman envisions the third space’s potential for revolution through a precise frame: the gendered, bodily loss within and outside a Middle Eastern diaspora.

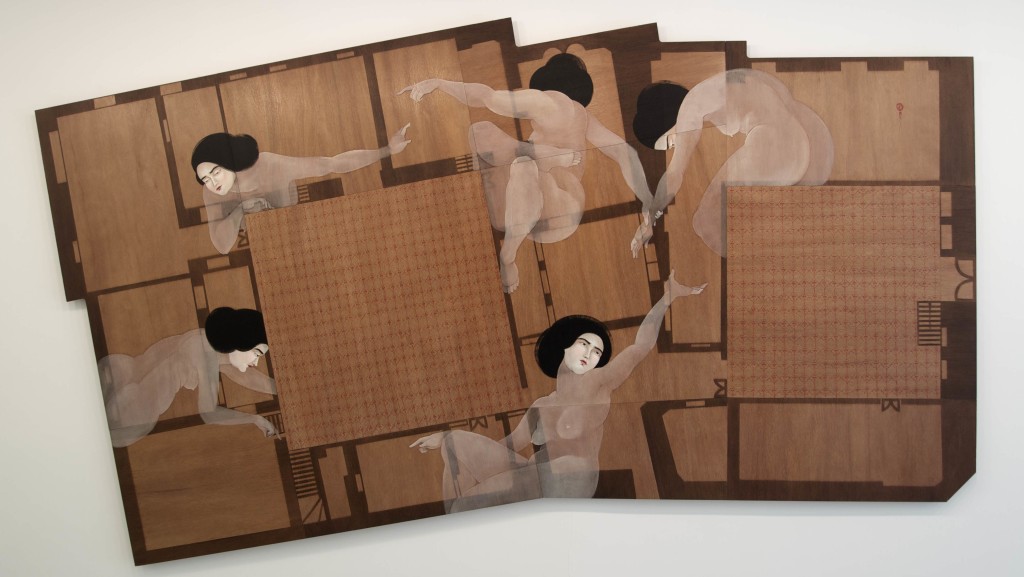

This idea of transforming the body can be found throughout the exhibition. In the piece Icosahedral Body, Kahraman creates an arabesque wooden sculpture formed through imagining scans of her own body. The disembodiment of Icosahedral speaks to the symbolic absence that immigrants, especially women or gender nonconforming folks, may experience when forcefully displaced. However, it is important to consider that even though pain is present, Icosahedral is also a site of activation, the piece’s movement bringing to mind the curvature of Islamic architecture. Kahraman relates the uneasiness of a body caught between presence and absence to her own childhood in the piece Bab El Sheikh. Within Bab El Sheikh, women sharing dark black hair and Botticelli white bodies inundate the floor plan of an Iraqi home; their origins are not Iraqi nor European, they are independent agents. Their bodies seep into rooms, the outlines of their torsos hazy but their presence palpable against the emptiness of the home. The connection between the body and the idea of home as tangible space is furthered in Kahraman’s writing as she states, “When our home sold, a part of me faded. We tried to hold on to it as long as we could, but my father has two daughters, and we could not have inherited the house,” the house in question being her childhood home in Baghdad. Within the literal and symbolic loss of home and space Kahraman disrupts the borders of the female body in such a way that excavates the hybridity of survival; one adapts to survive but such transformation necessitates a death. In Read Me From Right to Left, the body as a source of transformation and disruption is situated at the forefront of the piece. The same dark-haired figures gaze out towards the viewer, as portions of their bodies dissolve against the canvas. They are positioned in a similar pose against an essential swath of black. When closely examining their bodies, small rips and tears are made apparent. These perforations are woven into the canvas. While such intervention brings to mind the nature of a wound, it is the same break that allows for a malleability through which breadth and growth become possible. These bodies are ones who have survived.

Though Kahraman’s figures possess a somewhat haunting ambiguity, such indeterminacy is not detrimental to their agency nor the agency of female voices or collective stories they carry. Any questions that remain are urgent and necessary reminds that the diasporic experience is not neat or tidy. Narratives borne from those displaced are lineages of survival and considerations of how spaces and bodies can become agents of change. In the face of fascism such sentiments bear repeating as the voices of women of color, those displaced, and all who have resisted the oppression must be given their long overdue importance.

Hayv Kahraman: Acts of Reparation runs at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis until Dec 31, 2017.