In Advance of An Archive: The Joseph J. McPhee Jr. Research Library and Listening Room

by Patrick J. Reed

I. This is a story about jazz and thinking about jazz, and thinking about the moment both were on my mind when a teenager passing me in a car hurled a homophobic slur in my direction. True, the bag I was carrying was filled with zucchini and sake, but he did not know that; so I responded with a middle finger.

In that electric moment, a current within me jumped from one thought to another—from “the bird” to the Bird, so to speak; I remembered the power of defiance and, consequently, the power of jazz. Heretofore, I missed the politics embedded in the music; misunderstood its moxie, febrility, and lightning-flash inspirations. Do not mistake me; I am not arguing jazz (and by extension, improvisational or even experimental music) is some long-held, infinitely-elaborate “fuck you” to anti-gay sentiment, but is not jazz-at-large a long-held, infinitely-elaborate resistance to the oppressive status quo?

Is not this everything trembling in a blue note?

The illustrious Sun Ra, whose experimental music encompasses and surpasses most categories— jazz included—and whose aesthetic is a lodestar for queerness and Afrofuturism, certainly seemed to operate on the assumption that improvised words, improvised sounds, and whatever inspirations that followed were powerful enough to manifest the personal mythology according to which he lived. In Robert Mugge’s 1980 profile documentary, Sun Ra: A Joyful Noise, the artist, whose reputation as a self-styled, Egypto-revival man from Saturn, was by then well-known, said his music relayed “unknown things, impossible things, ancient things, [and] potential things” rooted in deep time. It suggested freedom unburdened by the shadow of unfreedom; it generated a different ontology.1

Sun Ra championed universalism, but spoke directly to a Black audience, whom he offered an exit from racist paradigms and an entrée into radical utopia. “They say history repeats itself. They say history repeats itself. Repeats itself,” he intones at the end of Mugge’s film, “but history is his story. It’s not my story. What’s your story?”2 His final question, delivered with a gentle smile, is less a rhetorical one than an invitation to speculate untold futures. Visions built upon a bespoke heritage that reclaims Black identity, and rejects the Eurocentric historical narrative that undermines it. As sociologist Tricia Rose explained in “Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose” by Mark Dery, “If you’re going to imagine yourself in the future, you have to imagine where you’ve come from; ancestor worship in Black culture is a way of countering a historical erasure.”3

In recent years, Afrofuturism gained momentum among artists reacting to far-right politics. Although, its presence in Black creative communities, and the problems it seeks to disable, are anything but new. Prominent art world figures such as Larry Achiampong, Arthur Jafa, and Cauleen Smith each work at the forefront of this movement—utilizing the moving image to explore issues of postcoloniality, the African diaspora, violence against Black bodies, Black identity contra white America, and Black identity uplifted by technology. In pop culture, Janelle Monáe’s “Cindi Mayweather” video and music enterprise from the early 2010s assumed the mantle of Sun Ra’s most Sci-fi tendencies, coupled with a hefty dose of machineage glamor. The 2018 blockbuster film Black Panther, directed by Ryan Coogler, dispelled any notions lingering about Afrofuturism’s status as a niche phenomenon or novelty.

Swept into the mainstream on a wave of exaltation, Afrofuturism also fell prey to the vorticose misusage that spins critical social issues into cultural caché. Consider, for example, Milchstraßenverkehrsordnung (Space is the Place), the August/September 2019 exhibition at Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin that sought to combine Elon Musk’s enthusiasm for colonizing outer space with Sun Ra’s aesthetic philosophies.4 That these two ideas are obviously incompatible apparently did not trigger alarms during the curatorial development of the show, nor did the egregious fact that all but three of the twenty-two participating artists on the roster were men, and all but one were white. The Internet, predictably, exploded on this point—the semi-anonymous cultural watchdog group, Soup du Jour (aka Soap du Jour) issuing an open letter to the curator, Bethanien’s artistic director Christoph Tannert, entitled “WHITEY ON THE MOON.” The letter charged the organizer with the exploitation of Afrofuturist concepts, disregard for nonwhite voices, and the perpetuation of white, patriarchal heteronormativity. Social media circulated news of the scandal with such efficiency that I knew of it before many of my colleagues in Berlin. The incident suggested something particular about the Internet: as an information ecosystem, the cultural climate of summer 2019 is the hottest on record to date.

II. Maggie Nelson wrote in The Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning (2011), her treatise on brutality in art and culture, about the perils of image flow that characterize the Internet. The book raises the ethical questions of what to do with images that spark outrage one day, and stultifies an increasingly desensitized public the next. A kindred peril, I would argue, is the false sense of erudition offered by the information structure that also supports the Internet-based image regime Nelson describes. The same structure responsible for the high-speed information exchange that makes an armchair guru out of anyone, on the subject of anything, is similarly entropic.5

Although the Internet has aided in dissolving barriers regarding who has access to what kinds of knowledge (depending on where in the world one finds oneself), it has also flattened the learning experience into a text-and-image putting green in which material qualities, degrees of import, and general discernment are themselves filtered through text and image, ad infinitum. The result: criticality, made defunct by the hive mind, is divorced from knowledge, and knowledge, denied its old correlation to empowerment, becomes cheaper than air.6

In part, it is the ubiquitous presence of the lens that has created these circumstances. But just as lenses bend light to form an image, so too do they distort reality. This old insight is worth repeating in a world glutted with phone cameras, dashboard cameras, ATM cameras, traffic cameras, police body cameras, supermarket self-checkout monitoring devices, computer cameras, underwater cameras, Google Maps satellite views, military surveillance, and the endless number of livestream cameras that document highways, tundras, international borders, animals in backyards, and Antarctica. This is, of course, nothing to say about those cameras that enter bodies and those that explore the firmament. Each iota of twenty-first-century existence is mediated through a lens and uploaded to a network.

Milchstraßenverkehrsordnung made a fad out of Afrofuturism; it was a gambit permitted under the conditions created by this faux omniscience, wherein the idea of wondering about the lives of others for the betterment of humanity—once an ethical responsibility—was supplanted by the nabbing of personal experiences that are decontextualized, disenfranchised, and prostituted as relevant cultural experience. Ironically, the backlash made a fad out of being outraged by Milchstraßenverkehrsordnung, such that those who were sincerely outraged, and those who defaulted to outrage because it was “trending,” generated more hype around the exhibition than any standard press coverage did or could.

III. Do not mistake me: I do not want to shut down the Internet or police its use. I do not propose a reinstatement of knowledge hierarchies long maintained by ivory-tower institutions. Nor am I railing against the democratizing possibilities of technology like camera phones.7 Such arguments are facile—moreover, they run counter to the basic tenets of Afrofuturism. But the need to run diagnostics on the ‘health’ of critical thinking, in the age of image and information saturation, is integral to living critically. Reconfiguring the “I see it, therefore I reiterate it” mentality, which believes itself always the expert, is necessary.

The frequent caveats, qualifications, and asides in this essay (one of which you are reading now) alone illustrate the degree that the see-it/reiterate-it formulation corrodes and complicates basic critical thinking, even under the most well-intentioned circumstances. I attempt to outmaneuver its deleterious effects, sentence by sentence, but I fear I am simply perpetuating the toxicity by participating in the same loop. One that routes protest into promotion, and dissent into complicity. I, too, am drinking from the poisoned river, but I am seeking the sweetwater.

IV. I have found the sweetwater. It is in the museums, libraries, and archives. It ripples in the IRL houses of study; the sites where one can verify facts beyond a checkmark badge. It is within these spaces that one can challenge veracity outside of an algorithmic echo chamber, with stable evidence instead of a wily open-source database. Moreover, the library is one of the last bastions where one can browse without being monitored.

The digitization of collections, although helpful for people who are without the access or wherewithal to visit these facilities, has done little to strengthen appreciation for studybased institutions. Their reputation for stuffiness precedes them, as does their need for climate-controlled rooms, trained caretakers, and demanding upkeep. God, the upkeep! runs the typical lament against archives by bureaucrats, who slash budgets and liquidate anything that fails to turn a profit. Archives, in particular, get a bad rep. They seem daunting and are often the subject of derision for their shortcomings; the most devastating being the sad fact that what is excluded from an archive is excluded from the historical record. This is one point where advocates for the Internet noösphere potentially have the upper-hand, but I posit the following: archives are cisterns for preserving knowledge derived from history. They can be corrected, or they can lead to further study that halts the erasure produced by what they lack. The Internet is a turbine, churning information taken from anywhere, that often propels a runaway international disinformation machine.8

V. Studying a document or object in person is essential to understanding its nature, the nature of its maker, and the nature of its collector. Material culture sustains heritage—the intelligence of the hand, and all the intimacy that comes from responding to an artifact.

Although artists like Achiampong, Jafa, and Smith use the lens as their modus operandi, they do so with a firm grounding within an archive. Jafa, who won the Venice Biennale’s 2019 Golden Lion for his film The White Album (2018), has accumulated over his lifetime a massive image archive that supplies inspiration for his films, as well as being an artwork in its own right. During a discussion with critic Jörg Heiser on the occasion of his exhibition ARTHUR JAFA: A SERIES OF UTTERLY IMPROBABLE, YET EXTRAORDINARY RENDITIONS at the JULIA STOSCHEK COLLECTION’s Berlin outpost in February 2018 (an event that I did attend in person, for all those keeping score on the internet-information paranoia front), the artist explained that he stores the image clippings in plastic to protect them from fingerprints—a testament that powerful images compel touch.9

Jazz and science fiction are Jafa’s two major influences, and within his sphere of thought, they come together often. In his conversation with Heiser, for example, he speaks of Miles Davis in nearly the same breath as Stanley Kubrik’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), a film he outlined as a story about “white people being confronted by the vastness of the Black universe.”10 In his work APEX (2013)—a potent installment within the artist’s ongoing examination of, as he put it, the catastrophic violence directed toward Black people—he activates his archive as a slideshow that juxtaposes Black cultural icons and images of science fiction with images of the most heinous, racist brutality.

Cauleen Smith’s Black Utopia LP (2012) also activates archival research through the slideshow format, although her source material is the preexisting Alton Abraham Collection of Sun Ra, housed at the Regenstein Library of the University of Chicago. Smith initiated the project in 2010, during her tenure as an artist-in-residence at Threewalls, a non-profit contemporary art space in Chicago, and it has since become a sort of archive in its own right—albeit one that evades the potential sclerosis of a traditional collection, thanks to its status as a living, breathing artwork. Described by Hyperallergic contributor Matt Turner, in his review of the project at the 2019 International Film Festival Rotterdam, as “…a kind of Afrofuturist collage of sound and language, rhapsodizing on the utopian potentials and possibilities of Black space travel and astrology,” Black Utopia LP is a cooler illustration of Sun Ra’s aspirations than one will find in Jafa’s apocalyptic montages.11

VI. The Series I: Biographical Inventory list of the “Guide to the Alton Abraham Collection of Sun Ra,” includes a slim entry: Box 1, Folder 49, John Corbett, “Inherit the Sun,” Down Beat, 1993.12

If one were unaware that the author of “Inherit the Sun” also happened to be the former custodian and forever donor of the Alton Abraham Collection, the mother lode of all things Sun Ra, to the University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center, then the poetry in the article’s title might not resonate like it does for those in the know. The collection was, of course, once the property of the man for whom it was named: Alton Abraham, Sun Ra’s pal on the terrestrial plane and long-time manager, but it transferred to John Corbett and his wife, Terri Kapsalis, shortly after Abraham’s passing in 1999. It remained under the couple’s care until 2007, when it moved to its current home.

Corbett, who is one half of the duo behind Chicago’s beloved gallery, Corbett vs. Dempsey, is a collecting fiend; while acquiring the Alton Abraham Collection was a boon, it only added to his already impressive cache. During a phone conversation in mid-July, Corbett informed me that he has, for the past thirty-five years, privately collected extremely rare posters, publications, ephemera, and archival material related to the history of 20th century art in Chicago and the Midwest, and, for the past fifteen years, done the same under the aegis of the gallery, with co-founder, Jim Dempsey.

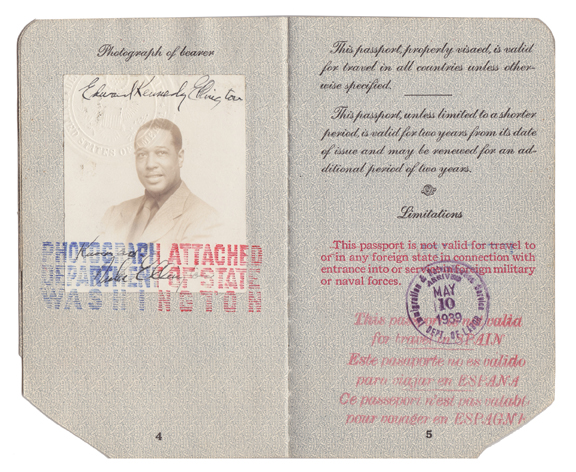

In February 2019, Corbett vs. Dempsey relocated from their original location to a significantly larger space on Chicago’s West Fulton Street, where they continue exhibiting, promoting, and collecting the notable artists of the Second City. The new location will also serve as the headquarters for The Joseph J. McPhee Jr. Research Library and Listening Room (aka The McPhee), an archive named in honor of the American jazz luminary, and founded upon the collections mentioned above, in addition to a vast jazz and experimental music module comprised of, but not limited to, ten thousand LPs, thousands of vinyl singles, yards upon yards of magnetic tape recordings, the musical archives of contemporary free improvising percussionist Paul Lytton, original drawings by Sun Ra, and Duke Ellington’s 1939 passport, which he carried during his passage through a Europe that was about to explode into war.

Paraphrasing Dempsey, Corbett expressed enthusiasm for the passport in particular because it tells the story of a single person’s experience at a level of detail that one cannot learn from mere descriptions of textbook rehashing. The object lures fascination because sustains its heritage—the emotions in the hand that held it—and all of the intimacy that comes with knowing that one’s proximity to the object reduces the proximity to the person who once owned it.

Proximities to The Joseph J. McPhee Jr. Research Library and Listening Room will be limited at first. It is still a treasure trove taking shape. But, in time, Corbett believes it will provide an invaluable resource for artists, curators, and other researchers who wish to conduct the kind of very specific analysis their collections will support. “We are material culture nerds,” he tells me. I think of them more as custodians of rare voices. There are, after all, objects and sounds in the archive that cannot be found anywhere else.

This is the story about jazz and thinking about jazz that was on my mind when that weasel in the passing car sent my mind on a boomerang’s path around Saturn. But it came back in time for the dawn of an archive, another cistern of still, golden light.

The Alton Abraham Collection of Sun Ra 1822–2008 can be found at the University of Chicago’s Library Special Collections, with the majority of the collection open to the public at request of the library staff. The Joseph J. McPhee Jr. Research Library and Listening Room is located within Corbett vs. Dempsey in Chicago.