Isa Genzken: I Love Michael Asher

by Brandon Sward

While I Love Michael Asher at Hauser Wirth & Schimmel is Isa Genzken’s first solo exhibition in California, it is not the artist’s first interaction with the state. By her late 20s, Genzken was teaching at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, which provided her with a travel grant she used to meet Michael Asher, who taught at the California Institute of the Arts from 1973 to 2008. Her work at the time consisted of smooth sculptures of lacquered wood she called “ellipsoids” and “hyperbolos.” The austerity of Genzken’s work at the time bears a similarity to Asher’s, which was similarly restrained and rarefied. Long associated with ‘institutional critique’—an inquiry into the supposed ‘neutrality’ of spaces within which art is shown—Asher’s interventions included adding and removing walls, recording deaccessions, and keeping a museum open for 24 hours a day. Although Genzken once shared with Asher a certain aesthetic sensibility, I Love Michael Asher presents the Genzken we have since come to know—sensuous and flamboyant.

Beneath her stylistic differences with Asher, Genzken shares many of the objectives traditionally associated with institutional critique, such as a desire to interrogate the relationship between art and how it is viewed—incorporating plinths into her works as objects themselves, thus destabilizing the boundary between displayer and displayed. Genzken refuses to allow the gallery and its apparatuses to recede into the background, thereby bringing art institutions and art objects onto the same level. Just a few miles away in space but almost a decade away in time, Michael Asher reconstructed all of the temporary walls built within the Santa Monica Museum of Art from 1998 to 2008. While such a gesture collapses critique into art, Genzken wants to hold open the space between the two, such that her work simultaneously speaks in both critical and aesthetic registers.

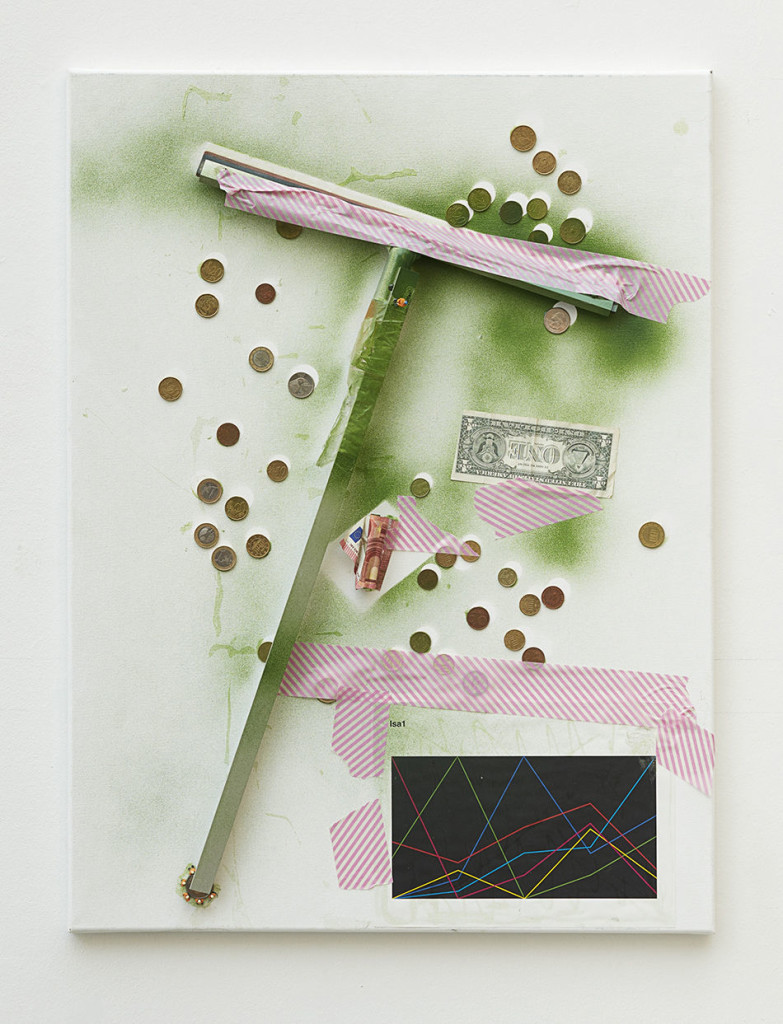

Questioning how art attains value, Genzken uses currency as a material by applying coinage and bank notes to her canvas. Is the resultant painting now worth more than the money upon it? One could, after all, pick the money off and go to the store—though the possibility of purchasing these works complicates this question, as the art object inevitably costs more than the chump change affixed to its surface. It is precisely this disconnect—between the price of manufacture, and the price of purchase—that Genzken exploits, a strategy continued by her crude scrawling of “ISA” in spray paint across multiple pieces. While they are not positioned in the familiar bottom-right corner of the canvas, these signatures proclaim authenticity. But unlike their historical precedents, the signatures also reference graffiti; one method of applying paint is viewed as art, and another a public nuisance. In a final interrogation of value, Genzken includes reproductions taken from the canon of Western art history, such as Caravaggio’s Boy Bitten by a Lizard. Although the value of art can be ascertained by how effectively it intervenes within art history, perhaps an insertion so blatant falls flat. A third option is that the work wavers in the sincerity with which it addresses history—it is precisely this inability to articulate what exactly is going on that makes Genzken interesting. Contrast with Asher’s participation in the Art Institute of Chicago’s “73rd American Exhibition,” wherein he relocated a patinated bronze cast of a 1788 marble sculpture of George Washington by French artist Jean Antoine Houdon from its usual position outside the museum’s entrance to Gallery 219, dedicated to European art of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. In other words, Asher made visible the mere decorative status of the sculpture by bringing it into conversation with other works from the same period and region.

Genzken challenges typical notions of completion. Installed along the gallery’s exterior wall facing the street is a window shipped to Los Angeles from the artist’s Berlin studio. The sill of the window—holding plants, aluminum cans, and more coins—is the quintessential image of the artist at work. One can almost envision Genzken drifting about her studio as sunlight filters through the windows, her fingers hovering over loose change on the shelf, trying to select which coins should adorn the canvas before her. It seems Genzken considers her process as much as part of her resultant work as the work itself.

Other pieces are presented half unpacked, shrouded in the remnants of shipping materials, resulting in another leveling. This time of those even further removed from Genzken than the gallerists: the workers ensuring her art safely made it across the Atlantic. This gesture is one of the most radical of I Love Michael Asher, since it brings to the status of art those who are almost certainly unaware of themselves as participating.

If institutional critique is to encourage dialogue around the deep ties of art with institutional life, then I Love Michael Asher certainly succeeds as such. The most important difference between Genzken and Asher is the former’s lower “barrier to entry”—one needs to know much less to understand her work than one needs for Asher; it is not possible to appreciate the fact that Asher is restoring a museum’s initial floor plan unless one knows what this earlier floor plan was. Genzken, on the other hand, is able to offer similar sorts of critique without presupposing an audience steeped in such arcana. Perhaps now we are able to envision an institutional critique more accessible than was possible in Asher’s time, perhaps now we can bring awareness of how art institutions function to precisely those who might benefit most from such a critique. If this is true, then Genzken represents what institutional critique might become in our present moment. As homage, I Love Michael Asher certainly contains moments of sincerity, but a fair amount of its love is tongue-in-cheek—it is perhaps the latter that undergirds the former.

I Love Michael Asher ran at Hauser Wirth & Schimmel from October 16 to December 31, 2016.