Jan Fabre: Angel of Metamorphosis

by Kostas Prapoglou

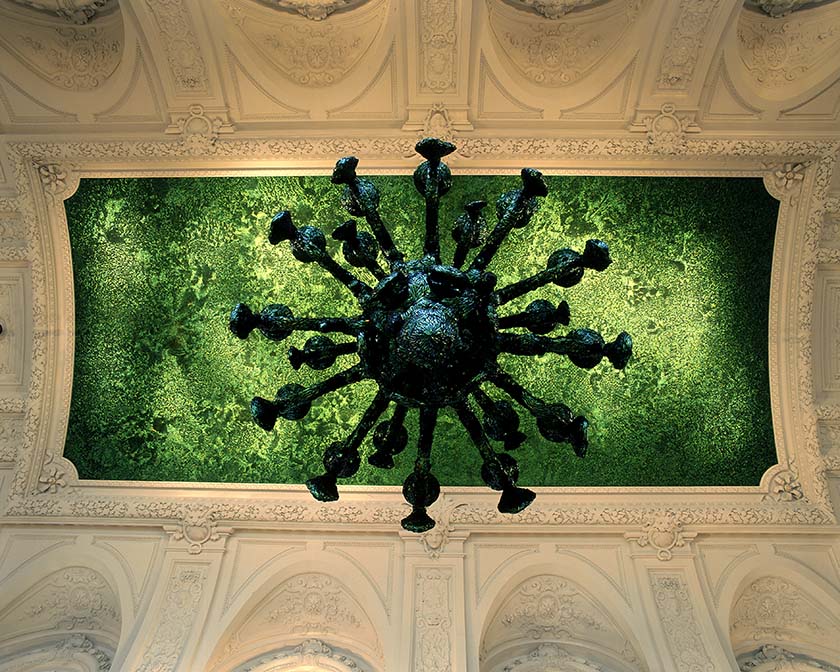

Belgian artist Jan Fabre is internationally known for his multidisciplinary practice that encompasses painting, sculpture, video, site-specific public installations, and performance. His work has been presented at numerous museums, among them the MAXXI in Rome, where he presented his seminal work Stigmata, Actions and Performances (1976–2013), and The Years of the Hour Blue: Drawings and Sculptures (1977–1992) the Busan Museum of Art in South Korea in 2013. He was the first living artist to be featured at the Louvre in Paris in 2008 with The Angel of Metamorphosis, a continuation of his provocative body of work that has been described as “actions” and “private performances,” which took place in the Flemish, Dutch, and German galleries among historic masterpieces on view as part of the collection. Other projects include Pietas held at Nuova Scuola Grande di Santa Maria della Misericordia in Venice (2011)—a series of five large marble sculptures that reinterpreted Michelangelo’s Pietà, organized to coincide with the 54th edition of the Venice Biennale—and the large scale installation Heaven of Delight at the Royal Palace in Brussels. Most recently, Fabre exhibited a 24-hour performance of Mount Olympus, shown at various locations, and his first solo show in London at Ronchini Gallery earlier this year.

I invited Fabre to discuss his work, inspirations, and future projects—below is a transcription of our conversation, which traversed his methods, associations to religion and theology, and mythological narratives.

KOSTAS PRAPOGLOU: Your first solo exhibition, which opened earlier this year at Ronchini Gallery in London, encompassed a body of work spanning 1992–2013. What was the response of the local audience, many of who were probably experiencing your work in a gallery environment for the first time?

JAN FABRE: The response was very good. The exhibition was first shown at Galleria Il Ponte in Florence—the same city that will also present a large-scale exhibition called Spiritual Guards, taking place at Forte Belvedere, Piazza della Signoria and the Palazzo Vecchio, to open in May and close at the end of October. The works shown in Knight of the Night [as part of this London exhibition] are borrowed from the collection of Luciano Maggini, and pivot around the theme of courtly romance—a central theme in my work. The exhibition encompasses many different eras of my work, while also being a good representation of my oeuvre. We included the performance film Lancelot (2004), but also a series of skulls covered in jewel beetles, as well as some select Bic blue ballpoint drawings that have not often been shown. The armors made out of scarabs in Salvator Mundi (1998) have been included before in the Louvre, as part of my exhibition L’Ange de la Métamorphose (2008).

KP: Part of your visual vocabulary engages with the imaginative use of insects, ranging from small-scale works, to large installations such as Heaven of Delight created for the Royal Palace in Brussels in 2002. How did this fascination emerge?

JF: I had been interested in the world of insects since a very young age. I built a small laboratory in the garden of my parents, The Nose / Nose Laboratory (1978–1979), to do my experiments as an entomologist-artist. During this period my uncle Jaak came by and said “Do you know that someone in the family was already studying insects?” and he gave me the beautiful books, manuscripts and drawings of Jean-Henri Fabre. He opened a new world for me that influenced my artistic universe.

I have been using scarabs [in my work] since the 1990s, which I collect through my entomologic contacts, as an artistic material. For me, they embody the idea of metamorphosis—a process that is very important to my work in general. Additionally, the drawings made with Bic ballpoint pens, from the series The Hour Blue, revolve around the theme of metamorphosis, just as the thousands of colors you can see in the beetles [incorporated into the sculptures] are all natural; they change according to the position from which you gaze upon them. This sort of ‘painting’ with light through the use of insects as a material can be found in my past work as well, in both the ceiling of the Royal Palace where I made Heaven of Delight as a royal commission in 2002, and more recently in the series that I created for the Tribute to Belgian Congo (2010–2013) and Tribute to Hieronymus Bosch in Congo (2011–2013).

KP: You have often produced works associated with religion and theology. Do you consider yourself a religious man, and to what extent do you feel that your personal beliefs mediate in your practice?

JF: My work is influenced by spirituality; certain elements are very important. For example, the cross, the tree of life, but also the model of Christ and stigmata are essential. I learned a lot [of this narrative] from my mother, who over dinner used to tell her own versions of biblical stories. At a young age, I took in a lot of these accounts and symbols. As an artist, my position is to take these elements and rethink them—the model of stigmata, for example, was reversed by my study of insects. In essence, I developed a model for future mankind, with an exoskeleton, impenetrable, unable to bleed. This new human has a new way of feeling and thinking, a new philosophy.

I think my personal beliefs dictate my work, because I am always rethinking these beliefs. The Man Who Bears the Cross (2015), which now permanently resides in the Cathedral of Our Lady in Antwerp, demonstrates this. It is a portrait of a man (the figure is a homage to my uncle Jaak) holding a cross in his hand—he is balancing this enormous weight, and examining it. The portrait shows not a man who is certain of his case, but an ‘everyman’ who is balancing his ideas and beliefs.

KP: Mount Olympus is a 24-hour long performance that was presented in various European locations, and investigated notions of time, as well as the shifting of narratives. With Greek mythology as its main source of inspiration, what were the aims and objectives of such a monumental project?

JF: My theatre goes back to the origins of tragedy. The tragedy developed from Dionysian rituals, in which intoxication meets reason and rules. An important principle to me is catharsis. In this piece, the viewer is confronted with some of the darkest passages from the history of mankind. They are taken along on a journey through extreme pain and horror. By confronting that deep suffering, their mind is cleansed. In my stagings, I try to do the same thing—I launch an attack on the audience. I take them on a journey. I show viewers images of man that they have repressed or forgotten about. I appeal to their violent impulses, to their dreams, their lust. Consequently, the theatre functions as a plague, just like Artaud said, in reference to Augustine who called the theatre a plague epidemic to be annihilated by any means necessary.

In a sense, I try to get to the marrow of the tragedy. I want to have my audience and actors learn through suffering. My theatre is a kind of cleansing ritual. I instigate a process of change. Not only the metamorphosis of the actor, but also of the viewer.

KP: Are there any plans to show this in other continents?

JF: We will perform the coming months in the Wiener Festwochen, the Jerusalem Festival, the Athens Festival, and the Theatre Biennale of Venice—later, we will also tour in Buenos Aires and Santiago De Chile.

KP: You have attracted media attention in the past for using unconventional work practices, such as the 8,000 slices of ham that covered the pillars of Aula University in Ghent, Belgium in 2000. How far would you go to test the boundaries of human nature, and aspects of its unique characteristics?

JF: Provocation is the evocation of the mind—the problem is that a lot of critics and journalists start using the word ‘provocation’ as something very negative. When I start a new creation, I never think about the idea to provoke spectators. Rather, I choose [the elements of the presentation] systematically, and as they are required, for both the research and the experiment. For me, what is something organic and very normal, is maybe for the outside world something more provocative. That tells something more about society then about the spirit of my work. Over the past few years, I have been involved in many interviews where writers ask me why I have created new visions—I never think in this term; I never think in terms of ‘new,’ ‘original,’ or ‘shocking.’ I just make the things that I personally think are necessary to make.

KP: What is your dream location to feature a performance?

JF: My upcoming solo performance, entitled Love is the Power Supreme, is in a fantastic location—the square in front of the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, on the occasion of my large-scale exhibition The Knight of Despair / The Warrior of Beauty, opening in October at the museum. .

KP: You have recently been appointed as the artistic director of the prestigious Athens Festival in Greece, which showcases cutting edge events, performances, theater, and art shows in urban and historical locations. How do you envisage your personal involvement as the leading figure of the festival, especially during this hectic political and socio-economic crisis in Greek history?

JF: I will be the artistic curator of the festival for the next four years. In this sense, curating for me does not simply mean programming—curating a festival is trying to find frictions, and links between the works of the artists I will present in the framework of the festival. It will be an exercise in consilience. For the first year, the theme will be Belgium, as I know the artistic scene of my country very well. For theater and dance, for example, I have chosen to present Franz Marijnen, Jan Lauwers, and Jan Decorte—but will also be inviting many more young theater makers and choreographers to participate. For visual art and performance art, I have chosen Luc Tuymans, Michaël Borremans, Thierry De Cordier, among others, as well as many younger Belgian artists. I will also invite writers, composers of Classical music, and writers of contemporary pop music. The Benaki Museum will also present an exhibition of my work, Stigmata: Actions & Performances (1976–2013), curated by Germano Celant. Programmatically, of course, we will be creating evenings dedicated to the Greek political situation and refugee problem.