Jasper Johns: Spy in the House of Love

by Stephen F. Eisenman

The moment of Jasper Johns was 1958. Eisenhower was president and almost nobody had heard of Vietnam. Frank Sinatra’s “Come Fly with Me” was No. 1 on the charts, and Nikita Khrushchev was forbidden to visit Disneyland. Also, that year, MOMA purchased from Leo Castelli, Johns’ Target with Four Faces (1955), Green Target (1955) and White Numbers (1957). In addition, Philip Johnson, MOMA’s architecture curator, bought Flag (1954-55) and agreed to later donate it to the museum.

Johns was only 28 at the time and he went on to create thousands more paintings, drawings, sculptures and prints, and he’s still working today. But everything since then has been stamped by the tenor of that fraught time. As the critic Moira Roth first noted, Johns’ “early work is a warehouse of Cold War metaphors.” It consists of flags, targets, maps, numbers and ciphers. It highlights the arts of subterfuge, concealment, indirection, disguise, and slight-of-hand, or what is known in the intelligence community as “tradecraft.” In those early years, Johns was a kind of double-agent, pledging allegiance to one Flag (red, white and blue), while offering equal obeisance to differently colored ones, including Flag on an Orange Field II, (1958) and White Flag (1960). His Map (1962-63), includes every state in the US, several Canadian provinces and two oceans, but is useless for reconnaissance. It’s a phantom map. Two Maps, made 25 years later is twice as useless. Lacking state, province and ocean names, it’s a ghost of a ghost, an American travesty.

Johns was in fact interested in espionage. He was a fan of Ian Fleming’s novels, and even posed as 007—legs apart and cocktail in his hand—in a photograph taken in Tokyo 1964. That same year, he painted Watchman (1964), a large and riveting picture dominated by the cast of a leg, thigh and buttocks nailed upside-down to a chair at the upper right. In some notes for Watchman (it’s unclear if he wrote them before or after completing the work) Johns wrote: “The Watchman falls ‘into’ the ‘trap’ of looking. The ‘spy’ is a different person… The spy must be ready to move, must be aware of his entrances and exits…. The spy must remember & must remember himself… The spy designs himself to be overlooked.” (Even the words into, spy and trap have to be put in scare quotes, placed at an ironic remove.) Johns is describing here an activity of self-erasure, or of going to ground, like the spy Alec Leamas in John Le Carre’s bestseller The Spy Who Came in From the Cold published in the UK in 1963 and the US the following year. Alec is a celebrated war veteran and spy who agrees to remain “in the cold” for one last assignment in order to snare a top, communist spy. In the book’s climactic scene, Leamas and his lover Liz are shot to death by East German watchmen in a tower as they attempt to climb over the wall separating East and West Berlin. John’s painting, with its grey surface, fragmented body, and red, yellow and blue flag, (close to the red, yellow and black of the East German flag), evokes the dramatic scene.

Johns’ Watchmen may have been inspired by still another source, one that suggests a different kind of concealment and disguise central to Johns’ practice: William Blake’s America a Prophesy (1793). The culmination of the prophesy occurs in the middle of the book, where the poet writes: “The morning comes, the night decays, the watchmen leave their stations.” The subsequent lines announce the liberation of every “enchained soul shut up in darkness and in sighing” and the commencement of a new age when “Empire is no more and the Lion and Wolf shall cease.” Blake illustrated the lines with the image of a muscular male nude with splayed legs and exposed genitals. It is an image of sexual as much as political freedom and as such was embraced by early avatars of gay liberation such as the poet Allen Ginsberg. Watchman thus connotes both the “enchained soul” terrified of public exposure as well as a longed-for erotic emancipation. Johns had already explored the themes a few years earlier with Painting with Two Balls (1960), Painting Bitten by a Man (1961), and The Critic Sees (1961) with its two open mouths within gloryhole eyeglasses.

For at least half a century, the key question concerning Jasper Johns has been whether his clandestine subjects and style were helpless responses to the political and sexual conformism of Cold War America, or purposeful provocations, “a performance of silence,“ as Jonathan Katz called it. Put more simply, it’s whether Johns has been painting from the closet or about the closet. My own view, clearly, is the latter. There are simply too many works that ostentatiously address patriotism on the one hand and masculine desire on the other, to say that Johns was passively enacting the self-effacement expected of political and sexual deviants in 1950s America. Take the case of Target with Plaster Casts (1955), made when Johns was just 25 and a new member of the queer circle that included Robert Rauschenberg, Merce Cunningham, John Cage, Ray Johnson and Cy Twombly. It consists of concentric blue-green and yellow circles on a red field—ostensibly a target for firearms practice—surmounted by lidded boxes containing casts of body parts including an ear, mouth, hand and penis. If you flip open the little wooden doors, you can peek at what’s underneath. In 1955, a man who flashed for another man in a bar, toilet or park had a good chance of being arrested. In one coordinated raid in Baltimore in October that year, 162 men were nabbed. In New York, Philadelphia, Washington or San Francisco, hundreds were typically arrested every month. Target with Plaster Casts addressed gay desire and police entrapment and lots of people at the time knew it — Alfred Barr for one. He chose the more chaste, and less successful, Target with Four Faces for MOMA’s collection.

But the mammoth retrospective on view at the Royal Academy (travelling in January to The Broad in Los Angeles) offers an opportunity to ask the old question again, but in a new, more insistent form consonant with John’s long career and our own dangerous times: How did it come to pass that works that arguably challenged both American patriotism and heterosexism came to be collected and adored by some of the most reactionary individuals and institutions in the United States, and not just the cold warriors at MOMA. In 1973, Two Maps (1965) sold at auction for $240,000, a record price for a living American artist. (It now belongs to the Whitney Museum—a gift of Leonard Lauder, chairman emeritus of the Estée Lauder Companies.) In 1980, the Whitney Museum paid $1 million for Three Flags (1958). In 2006, the Chicago hedge-fund billionaire (and future Trump supporter) Ken Griffin bought False Start (1959) for $80 million. In 2010, another hedge fund maven, Steven A. Cohen, (a Chris Christie man) bought Flag (1958) for $110 million. Whatever criticism of American jingoism may have been implied by Flag, (painted the year “under God” was added to the Pledge of Allegiance), or US imperialism by Two Maps (painted the year 200,000 American troops landed in Vietnam), was apparently vitiated by the time they were acquired by the new titans of real estate and finance capital.

In fact, the process by which ostensibly political works are rendered otiose—and extremely valuable—is not so mysterious as it is sometimes made out to be, and not much time is needed. In the case of Johns, there occurred a kind of perfect storm consisting of: 1) an artist of undoubted ability (the sheer painterly dexterity of the encaustic paintings from about 1954–58 is breathtaking); 2) subject matter that is provocative but not obviously so; 3) the evident exhaustion of the formerly reigning Abstract Expressionism (death, mental illness and over-exposure took their tolls); 4) a growing market for collectibles among a power and financial elite increasingly unconcerned about ostentation; 5) the rise of museums of modern and contemporary art; 6) college educated artists, art critics and curators who can explicate difficult works; and 7) following the global crash of 1973–74, a global, neo-liberal turn to investment in real estate, complex financial instruments, and commodities such as precious metals, jewels and works of art. Jasper Johns remains today an investment lodestar.

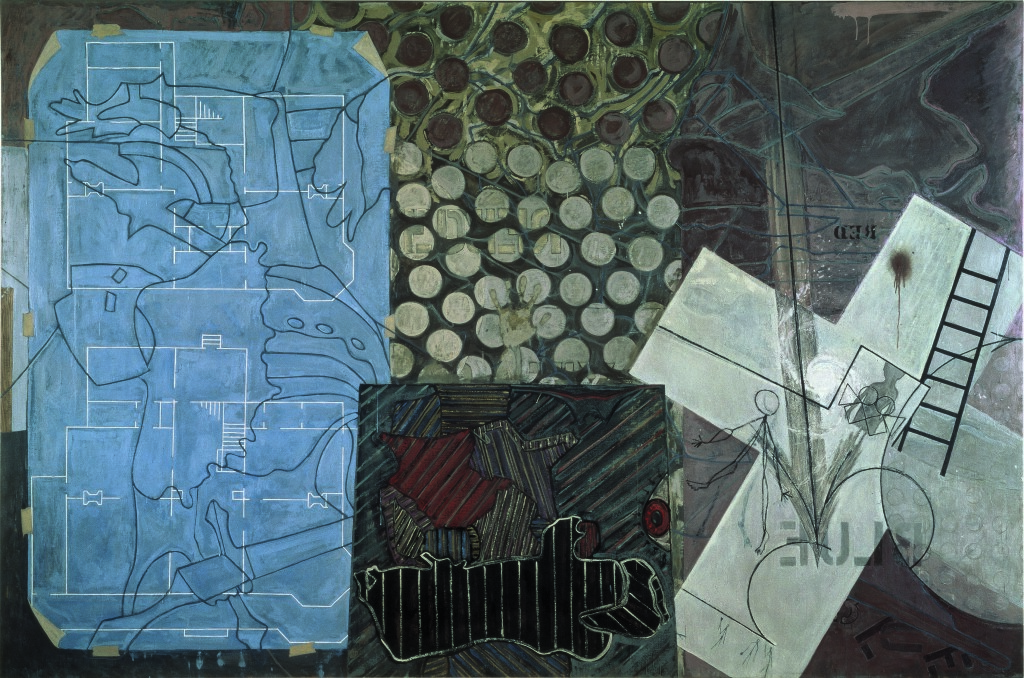

All that aside, the career—especially the first half of it—was remarkable. The images themselves are indelible as signs, expressions of the Gestalt psychology that dominated theories of mind and perception in the 1950s and early ‘60s. The concern with the making of meaning is intellectually bracing. It was present from the very start of Johns’ career but was validated and enriched by his reading of the Viennese linguistic philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein in the 1960s. The attention to pattern, notable in the Dutch Wives and Corpse and Mirror series (among other works) from the middle 1970s, alerted viewers to the visual pleasures, as well as oppressiveness of mass manufactured flooring, paving, upholstery, wallpaper, fencings, and building facades. Johns’ use of suspended or applied rulers, brooms, string, wires, discs, and other measuring devices suggests the reigning tyranny of reason and logic over feeling.

Among the most moving pictures Johns ever made was In Memory of My Feelings —Frank O’Hara (1961). It’s a quiet evocation of a poet and friend who was dedicated to what he called “personism”— loving attention to another being. Johns’ grey, white and black painting is split in the middle, the two parts attached by hinges. At left, a spoon and fork are suspended in front of the canvas. The picture is all about pairing and difference, proximity and distance, expression and diffidence. In this work at least, there is little or no reference to spying and tradecraft, and no resort to subterfuge and concealment. The artist here was at his unguarded best, bracingly removed from the cold war metaphors and queer anxieties that otherwise framed his early art and shaped his long career.

Jasper Johns: ‘Something Resembling Truth’ runs at the Royal Academy of Arts until December 10 2017.