John Stezaker: The Truth of Masks

by Stephanie Cristello

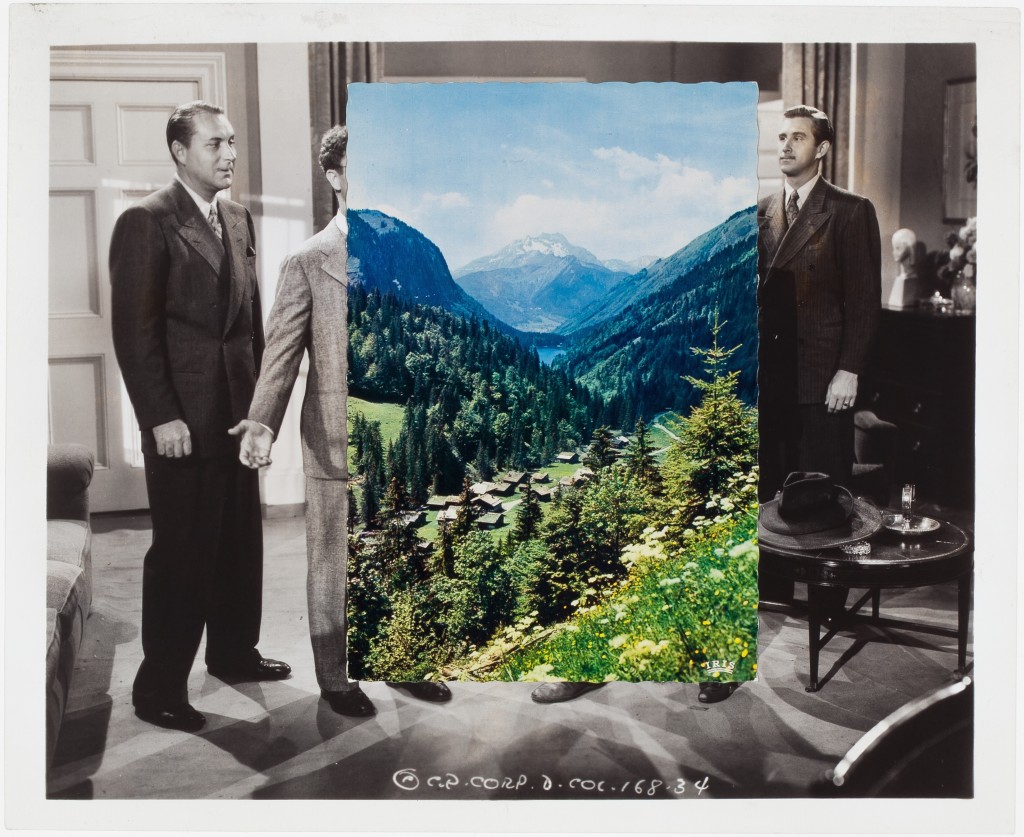

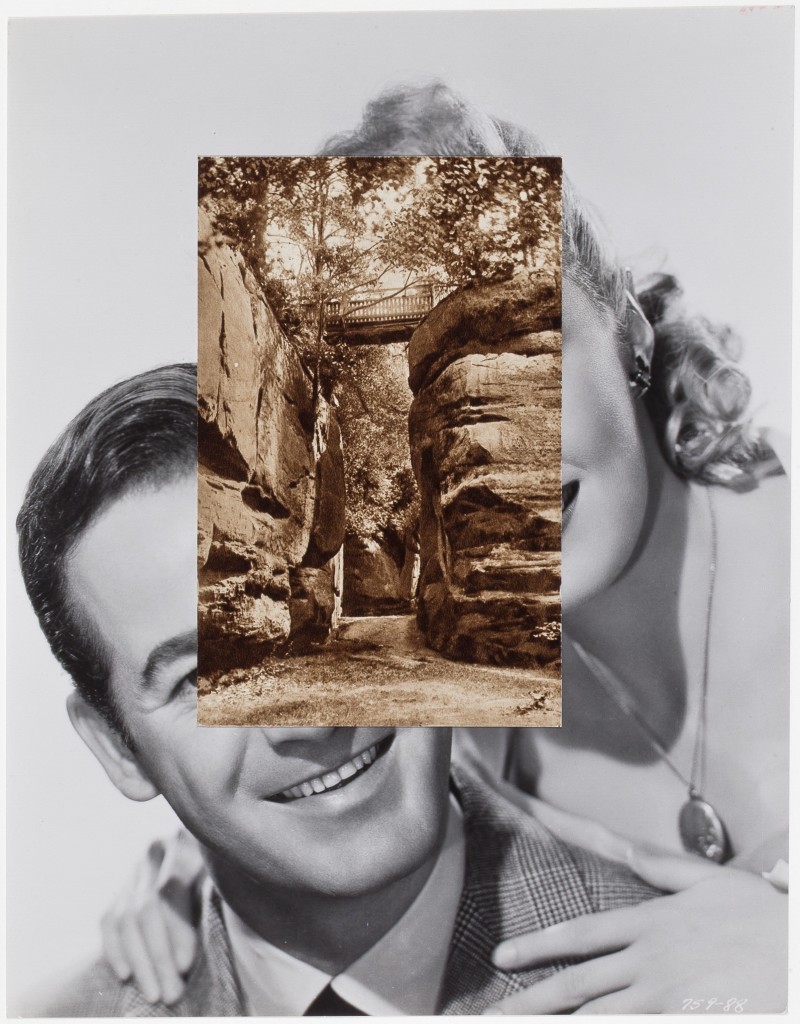

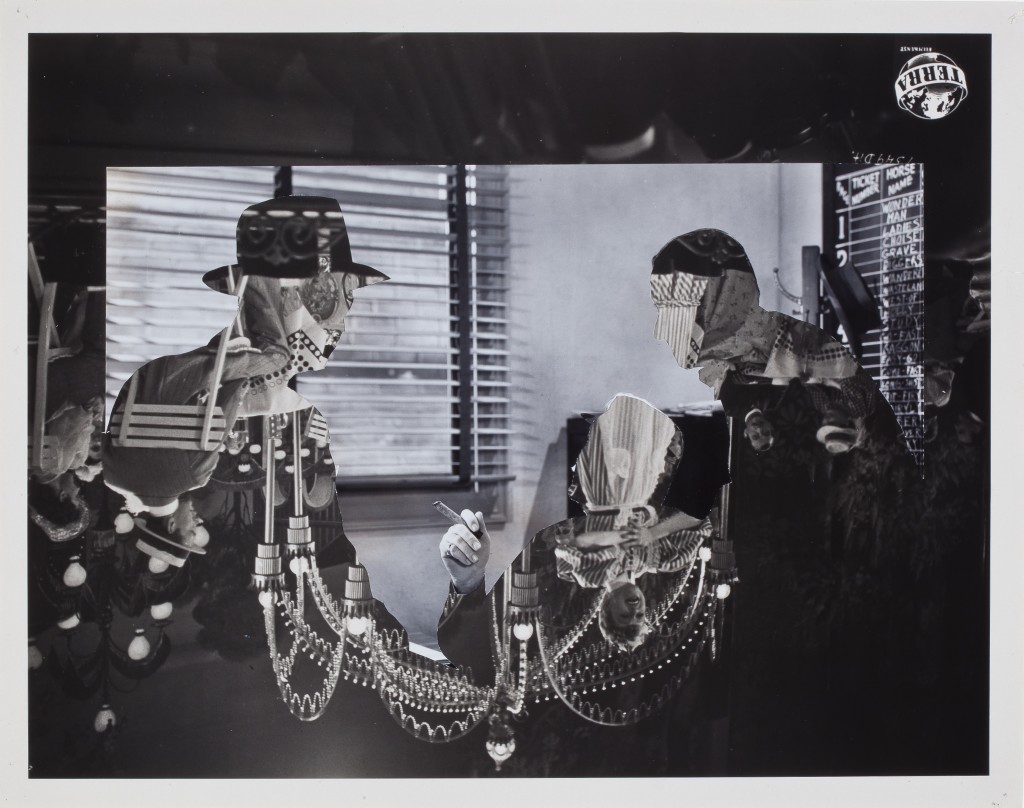

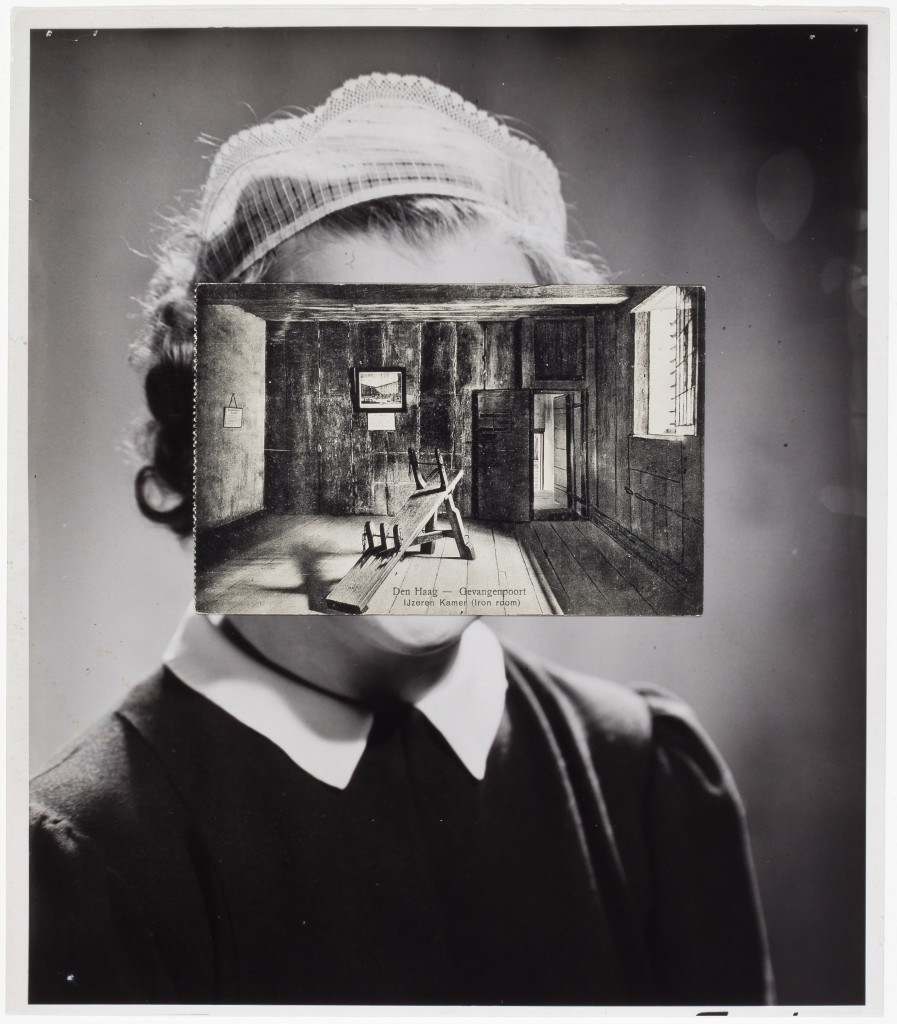

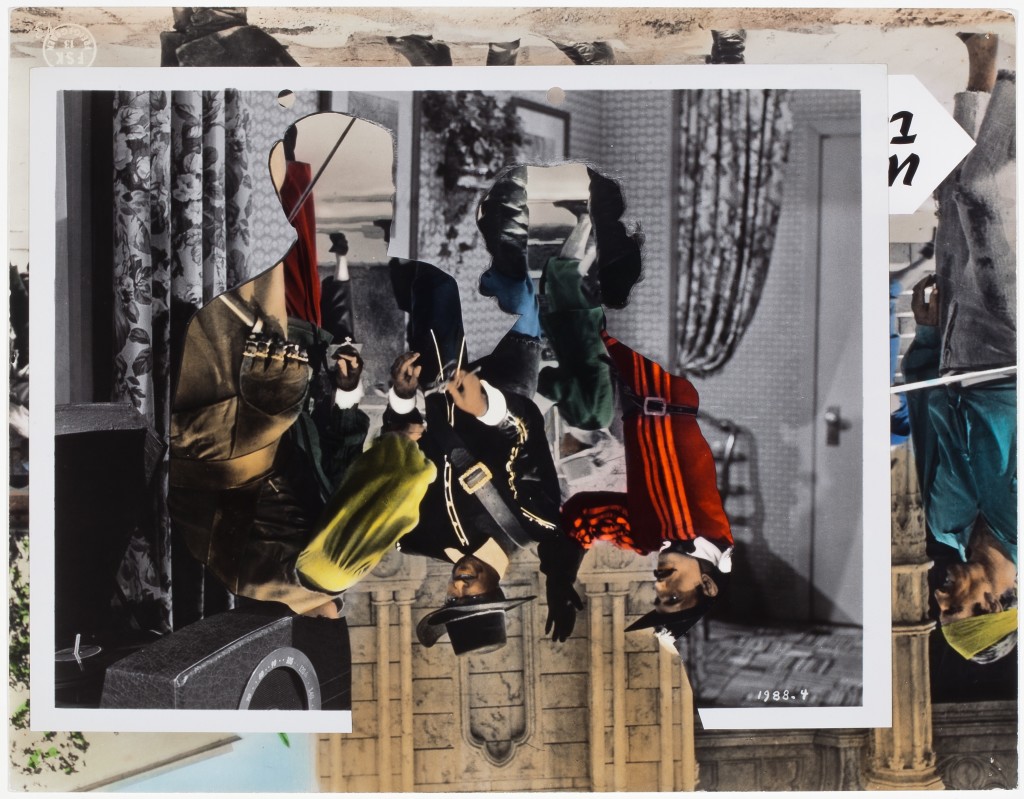

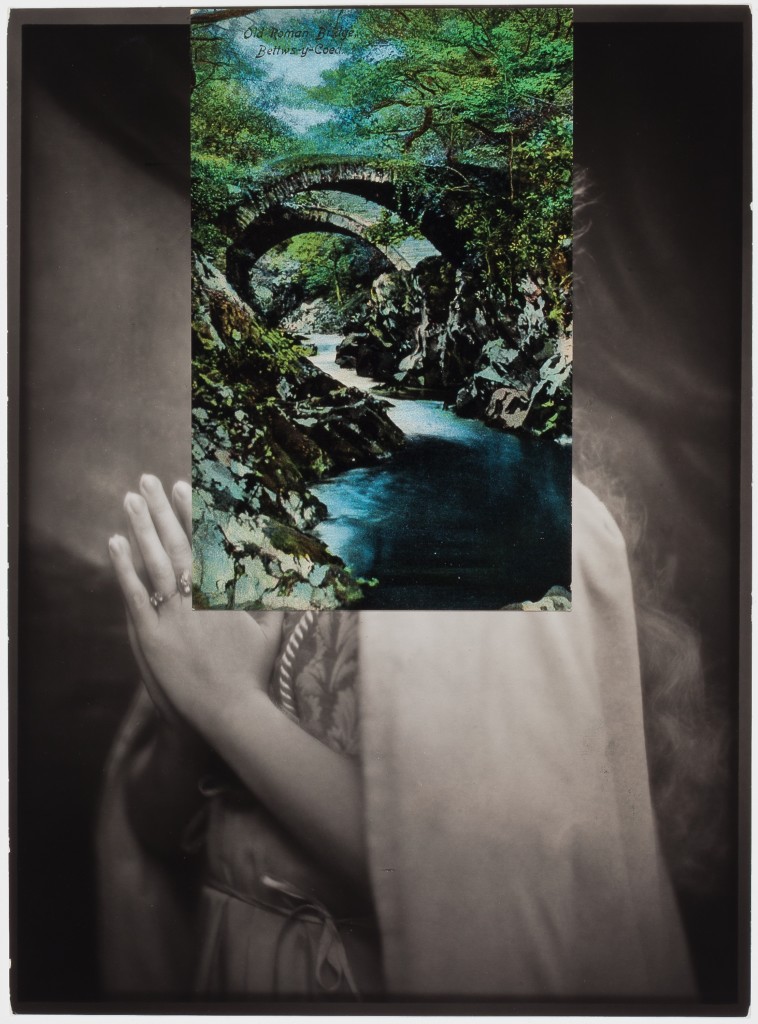

For British photographer John Stezaker, the truth happens on stage. While contained within the plane of the photograph, his sharp and precise compositions exact a world that exists just outside of the image—at once materially secular and trans-substantially sublime. For him, the conversation about the image is elsewhere; the photograph is a provocation. The body of work included in The Truth of Masks, currently on view at Richard Gray Gallery in Chicago, is serially formulaic—a collection of collage works that marry two types of images, one plainly placed over the other, to create one seamless surface—yet resists any type of easy categorization of experience. In fact, the experiences are quite traversing, each image suspending the viewer’s understanding of space by distancing a familiar interaction with often aesthetically recognizable found photographs toward a more fluid understanding of time, and one’s place within it. While the images Stezaker works with belong to pre-modern period, these works are intensely contemporary. By coalescing two antiquated forms of image making—vintage postcards and Hollywood film stills—into a single frame, these combines hold the status of the image in an unapologetically tenuous position. They operate as illusions in plain sight.

I spoke with Stezaker on the concepts in his work—we touched on the shared affect of the exotic image in both expeditionary photography and Hollywood film, the intersection between scientific understandings of matter in alchemical processes and the translation of these theories into photography, as well as American and British vernacular approaches to stillness, among other subjects. Below is a transcription of our exchange.

Stephanie Cristello: I wanted to start with what we spoke about yesterday—specifically about what you had said about the distancing of your relationship to the image, and the idea of the quest. What I find interesting is how you superimpose images on top of one another, a two-part process. The images that lie on top belong to a vernacular that used to be a very magnificent experience, which one had to travel far distances to see—images of canyons, forests, and caves. Very expeditionary. In terms of the touristic experience, these postcard images—from the time period they belong to—once used to take quite a long time to capture. How do you frame the relationship of the images to one another?

John Stezaker: Yes, I think I had mentioned to you that I had begun collecting postcards very early on. When I started making collage work in the late 60s and early 70s, I already had quite a substantial collection of these postcards, even before the first film still I worked with came into my possession. The film stills did not start for me until the mid 70s, and the moment I put a postcard on top of a 10 x 8 film still, something magical occurred. I did not know whether it was the proportion—the fact that a postcard was exactly a quarter of the ratio—but placed in the center it took on a major part of what would be regarded as the spectacle in my work; the focal point of the cinematic image. This interested me—because in cinematic images, you are always attracted to what is moving, and that is always the central part of a film still. Film stills are ‘centered’ images: you are directed to look at exactly what is in the middle. Once you put a postcard over that, you have obscured the main point.

SC: The idea of a still has such a different feeling than a photograph. One gets the sense of what comes before and what comes after the image—the stasis is a lie.

JS: It suggests that, yes, but of course it isn’t. There is a duplicity in the form, and that is what I enjoy about film stills. They pretend to be a moment from the film—in a sense, when they were presented in cinema foyers where they used to be—they were samples, tiny bits of the continuum. But in fact, they were much more like a menu. What would happen, classically, is a film would be filmed with a camera, and then a still photographer would come along and arrange the second take for the still image. I have heard descriptions of the actors saying “oh yes, we’re doing this again.” And somehow, they have to find the climatic moment within that scene in order to reenact it. The English films stills have a tendency to use the same tripod position; you could almost see it as extracted from the film. American films tended not to; they were much more variant.

SC: Not quite as recognizable as a trope—

JS: Exactly. And very often, for example, and especially in American stills, pre-Hollywood ones at least, you get characters all together in the same frame that do not even appear together in the actual film. Complete falsifications. I prefer the English ones, which are slightly closer to this idea of seeming to be extracted.

SC: The cultural idea of stillness is different—

JS: Yes, that very act of posing is already a falsification; it’s not the way that actual movement occurs.

SC: It is more of a tableau. It reminds me of the story of the first action scene shot of an airplane, it must have been in the 1920s—a very elaborate ordeal, meant to be an epic chase scene. Very fast paced, very exciting. When the director got the footage back, much to the surprise of everyone involved on the set, it was a complete failure. While the feeling of speed was an inherent part of the filming process, it did not translate on film. There were no clouds in the sky that day. There was nothing for the plane to be moving fast in relation to; it might as well have been standing still.

That scenery can have such an impact on stillness is I think a large part of your project.

JS: Yes, and I think all art—since the earliest works—have been an attempt to hold the image against the force of time. I think I am participating in the same act, but as a sort of attempt to hold onto what is forever slipping away. Perhaps now it is informed by a different set of social circumstances, but nonetheless. ‘Cinematic vision’ seemed to me to be a form of blindness. You never really do see the film image; you are always waiting for the next image to reveal something about the one that came before.

SC: I believe that was what you were saying more broadly about narrative as well—that it removes your ability to see an image.

JS: Exactly right, in cinema, the image becomes completely legible—and legibility is not seeing. Legibility is reading.

SC: Yet it feels like your work is not entirely formal; I do not think it is absolved of narrative. It seems like the narrative is more ontological—about the image.

JS: You might be right, that is an interesting thought. Can you have an ontological narrative, or a narrative that is about ontology? I do not know, but it is good to think about. Certainly, I am fascinated by what happens when you suspend an image from its narrative, and from its legibility, and of course from its association with words—which is something we have not yet discussed. By removing the discourse that is going on in the narrative, you take away any text that may have explained what is said to be happening in relation to the image.

SC: Which is such a Classical way of thinking: that words are explanatory and feelings are otherwise. For me, there is this sort of debate within the constriction of the photographs between language and feeling—or that those are two processes that you are synthesizing. The photographs are not entirely analytical, but they are also not entirely poetic.

JS: That’s a very interesting thought.

SC: Would you say that the aesthetics of the images you work with—which are all evocative of the 1940s—operate as another type of resistance to time, in the same way the collages attempt resist narrative in favor of the image? When you were first making these works, they were still historic, belonging to an older time. What is your relationship to this nostalgia?

JS: Yes—when I was a child, I rarely went to the cinema; my earliest experiences were of the film stills on the outside of the cinema rather than of the films themselves. Later on as an adult I tended to wait until the main feature was over – the latest releases which would be color movies and I would turn up deliberately late to watch the B Movies, which were always from at least a decade earlier. I do not know what really drew me to those in the first place, but as a child I remember looking at these images on the outside of the cinema and being drawn very much to black and white: the shadowy world of film noir. I think with time, I have realized that this is in fact a fascination that characterizes quite a lot of art. After Joseph Cornell is a good example: people are drawn to images before their time. They are fascinated by a world in which they are not present. I think it could also be a way as looking toward a world in which one is no longer present—somehow addressing the world after one’s death through looking at images that come before one’s birth. Burke defined the sublime in very similar terms. He talks about the sublime as being an experience in the world in the absence of the human.

SC: I love Edmund Burke. Vastness! In fact, that same sense of vastness only ever exists as a snapshot in your work. The photographs operate like figures, or illustrations to that experience, but only as icons to that feeling of the sublime without providing the experience itself.

JS: I often think, actually, of my work in relation to the sublime as a kind of miniaturization.

SC: The miniature and the gigantic.

JS: Yes, in the same way that these pre-war postcards make enormous environments small. Rather than focusing on the surrounding human, I am inserting them inside another image—exaggerating that miniaturization process. By reversing the idea that events ‘take place,’ or that human actions exist in a world—instead, I am inserting a world into human action.

SC: It is almost like a chasm—

JS: Yes, it is a void. A deliberate void at the heart of narrative. I never really considered it in those terms exactly, but that is quite right. It is like putting a void inside of the image, very much exposing the emptiness of the uninhabited quality of the cinematic image from the world I never lived in.

SC: That process is very much a trademark of conceptual practices—the sort of ‘removal’ of the artist from the process of the work, but in the most literal of senses. Would you say that this method has something to do with your experience during the formation of early conceptual art?

JS: Possibly—it is very much about loss of self. I also think of film images as somehow operating left to right. That somehow the postcard acts as a space that takes you behind the image, that promotes depth, a space beyond, a movement that is denied by the surface of the image.

SC: Postcards also have a different potential life—they literally move, around the world, in ways that film stills do not. Is the idea of export important to you?

JS: Yes—when I first started making that point of connection, there is a particular piece that was the first. It is a picture of a railway train, not actually a landscape, but I did think about calling the series Here and Now, because of the idea that the film still was “now”—a sort of time-image, and that the postcard was a space-image. And I realized that this was a total simplification, because in fact both were temporalized images. The postcards moved around the world, and the film still moved within itself. Two intersections.

The other thing was that I found myself more drawn to pre-war postcards and post-war film stills. Which was interesting. Someone did a survey of my work and determined that the mean time of the film stills were in the 1940s just before I was born; parental images. The postcards, however, came from my grandparents’ period — the 20s and 30s mainly.

SC: For me, it’s the intersection between the ‘expedition’ and ‘Hollywood’—

JS: Two forms of exoticism [laughs].

SC: The imagination of the other plays into your work too. The images are always searching for elsewhere.

JS: Absolutely. I felt that was always my conviction. My interest in the photograph is not to do with its naturalism in any way, but quite the opposite: what it reveals of the unseen, the unknowable. Are you familiar with Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space?

SC: It is one of my favourites.

JS: For me, the removal of the part of a film still, or the insertion of a postcard is much the same thing. It is creating out of a complete image—something that has a necessary, technological, seamless completion—a kind of ruin, a built-in incompletion. Bachelard talks about reverie, and the attachment to the image, which is one I suppose I most desire, as being conditional on what he calls the dialectics of inside and outside. Because what I have been doing is reversing those—creating an obvious dialectic where the outside is internalized.

SC: It makes me think of the title of Bas Jan Ader’s documentary, Here is Always Somewhere Else. In many ways, this is the same conceit of your photographs—there is the sense that one has never quite arrived at the image. That arrival is impossible, a sort of non-place. As simple as the constrictions may seem, they are not stable images.

JS: Yes, I think I am always trying to take away from an image in some way, to reveal its fragmentary and impartial nature. Bachelard makes a similar point; the dominant sites of reverie for him are spaces that are broken or partial, in which interior and exterior interpenetrate. Forests—which are closed but open—caves, ruins. I had been reading The Poetics of Space in the 70s, though it was not as if I had a program in mind. Now I realize that the masks I was working on were essentially those sorts of spaces.

SC: I think ruins, as an archetype, are one of the most important forms in your work—especially in terms of exoticism or symbolism in painting, the ruin very much belongs to that language. When you think about those paintings—which were made in the 1890s, but made to look stylistically medieval—I feel like the same sort of aesthetic jump is being made here, but with Hollywood.

JS: I suppose that the ‘desire’ I was speaking about earlier is to be a part of the world we perceive; to have our own autonomy, not to abandon ourselves. That is part of the sublime—which is an abandonment of self, but also a protection of self. We like spaces that are punctuated. I feel like that is what I am doing all the time: punctuating space.

SC: What about ruins as the imperfect mark of history?

JS: Yes, in fact there is a whole category of my work that I call the ‘damaged pieces,’ those are my favourite. There is a book coming out soon of these assisted ready-mades. There are stains, cracks, fissures, punctuations, and holes. Doesn’t Walter Benjamin say something like that about obsolescence; that it reveals the underside of history, that it is a vantage point on what is overlooked by history, what is forgotten.

SC: One of my favourite objects is a stone bust that I found tucked away on the second floor of the Bode Museum in Berlin. It was damaged in a fire during the war, and in many ways shared the same characteristics the same affliction would cause on a person on the surface of the sculpture. It was very human. It always fascinated me that it was saved, and preserved on view in an institution dedicated to Classical and Renaissance objects.

JS: I think a lot of our fascination with Classical art is its damage. We are obsessed with the white marble of antiquity, when of course we know that they were painted originally—as polychrome sculptures. I just visited the Dionysos Unmasked exhibition here at the Art Institute of Chicago, and I always love going to those sorts of shows because it is just a compendium of damage. There is an amazing piece there of a full-length figure of a female actor, and she is holding in her hand the mask of tragedy—but the sculpture has no head. A Surrealist could not create a more compelling image!

Recently, I have been working with a collection of broken mannequin parts for a show I have upcoming in Brussels. I found a whole box of mannequin hands with broken fingers and missing parts in 1976—I have shown one or two occasionally, but for this I have them all out on plinths. There is another box, which are very similar to these Classical busts we are talking about, in which there are a collection of mannequin heads that have lost their noses.

SC: That is always the first thing to go—

JS: One wonderful thing about the mannequins though, which is different from when it is in marble, is that the missing noses create a hole. They become, in this way, an image of death.

SC: For me, and perhaps it is because I am a synaesthete, the nose being the first thing to go missing makes perfect sense. Scent is the only sense that is essentially eliminated after death. Every other sense has a trace or facsimile—for sound it is the written word, for vision it is the photograph, etc.

JS: How interesting, I never thought about it like that, but you are quite right. Arcades of sculptures forever without scent.

SC: What about alchemy?

JS: Alchemy! Well I’ve read a lot on the subject, how did you guess?

SC: All of your images seem, not like a sleight of hand, but as being versed in the early phases of magic. They appear to have the effect of a séance, where the subjects in the photographs you are sampling from, and the image on top, seem to create either a distraction or possession of the characters pictured. Like they are seeing an apparition, or a ghost, that we are not able to see.

JS: Yes, and that was exactly how I felt about them when I was making these works. It seems slightly comic as well. But it is this sort of strange abandonment of the world. I have sometimes described my work as a kind of reverse alchemy, because in a way alchemical distillation is always an attempt to arrive at purity—you get rid of what’s called the negrido, a term that refers to the obscurity that prevents you from getting the true form.

SC: This dives directly into obscurity—

JS: Yes, this gets rid of the transparency, and holds onto the negrido—the incidental detail; the things you would discard during the reading of the image. If you are trying to consume an image as a reader, as in cinema, then you are ignoring a lot of what is going on in the periphery. These little details actually tell you about the image as a simulation rather than a reality. They kind of arrest the image.

SC: There is almost a suspension, or magical thinking, required to access these works.

JS: Of course as you know, Bachelard was fascinated by alchemy, and my favorite book of his is not actually The Poetics of Space, but The Psychoanalysis of Fire. It comes closest to his earlier writings and interest in science. He had felt that science had lost its relationship with the material of the world—post-Einstein and even post-Newton—and he felt that art was the only access we had to that alchemical relationship with matter. Matter, for him, is the unconscious.

SC: Or perhaps that art is the only vehicle for our senses to process that type of scientific information?

JS: Precisely. He deviates quite strongly from the Freudian definition of the unconscious as a separate realm. For him, he insists that the unconscious is matter itself. That matter is what we cannot perceive. Photography is about the unseen or the unseeable—if I had a claim to one thing I would like to say my work is about, I would say that it is about matter: a confrontation with the material.

John Stezaker, The Truth of Masks, runs at Richard Gray Gallery through December 12, 2015.